It wasn’t your ordinary B&B. The flowery chintz couch and the blossom-filled chintz wallpaper made the living room look like a psychedelic trip. Ceramic crocks of flour and sugar lined the countertop of the old-fashioned kitchen, and there was even one filled with homemade granola. I wondered whether our bill would be higher if I sneaked some.An odd metal contraption that looked like a rolling pin inside a metal canister hung on the wall. And an upholstered chair had front legs that were 4 inches (10 cm) shorter than its hind legs.

It wasn’t your ordinary B&B. The flowery chintz couch and the blossom-filled chintz wallpaper made the living room look like a psychedelic trip. Ceramic crocks of flour and sugar lined the countertop of the old-fashioned kitchen, and there was even one filled with homemade granola. I wondered whether our bill would be higher if I sneaked some.An odd metal contraption that looked like a rolling pin inside a metal canister hung on the wall. And an upholstered chair had front legs that were 4 inches (10 cm) shorter than its hind legs.

I was pondering the possible meaning of these strange items when there was a knock at the door, and a young woman in a long gingham dress and lace apron bustled in and took charge of our kitchen, whipping up a batch of apple pancakes and cutting up fruit.

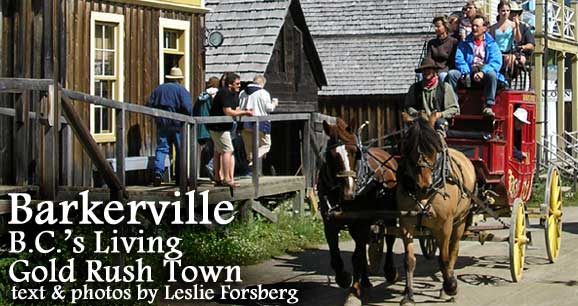

Definitely not what I expect at a B&B. But then, nothing about our stay so far had been normal. The night before we had parked our car outside the stockade-like gates of Barkerville, and gotten a ride on a stage coach to the Kelly House.

Horse-drawn conveyances are the only sort allowed in Barkerville, a historic theme town situated about 55 miles (88 km) east of the city of Quesnel, at the end of Highway 26 in central British Columbia. And we awoke to the dragging sound of the dirt street outside the window being graded by a two-horse team pulling a metal bar.

The mysteries soon became clear, as our cook, Alicia, explained. The metal contraption on the wall was a sausage maker, the oddly tilting chair was for hoopskirt-wearing women, so that their skirts would not tilt upward, showing off underthings, when seated. Who knew this was a problem?

“I bet they didn’t have mangoes back then,” said my husband, Eric, with a raised eyebrow, as Alicia began slicing the tropical fruit. “Actually, if they could afford it, they brought it in, including champagne and caviar,” said Alicia. She put the mangoes and other fruits into a cut-glass bowl and arranged ornate silverware on the damask-decked table.

It’s hard to imagine how early settlers could afford such expensive products, let alone get them to such a remote outpost. However, it wasn’t the typical early Canadian town, filled with poor people scrapping to make a living off the land. Barkerville was born in 1862 following the discovery of gold on nearby Williams Creek, four years earlier.

The town grew quickly to accommodate fortune seekers from around the world; by the end of the year, 30,000 miners called Barkerville home, with shanties and saloons crowded cheek by jowl. With the completion of the Cariboo Wagon Road in 1865, the town was much easier to get to, and the population swelled even more, until it became the largest city west of Chicago and north of San Francisco.

The town in the middle of the woods was a supply and social center for miners, complete with numerous saloons, dance halls, general stores and boarding houses. Much of the early “entertainment” consisted of drinking, gambling and frequenting houses of ill repute, but there was also a church, a literary society and a theater.

In 1868, the town burned down nearly to the ground, yet within six weeks more than 90 buildings had been rebuilt. Eventually, the gold petered out, and residents moved on to the nearby town of Wells and other areas where gold was still plentiful. By the turn of the 20th century, Barkerville was essentially a ghost town.

The town experienced a small revival in the 1930s during the Great Depression, when the price of gold rose, yet many lean years followed. In 1958 the final residents of the town were bought out and moved to nearby New Barkerville. The town was designated a historic provincial park, and was gradually restored to its glory days of 1869 through 1885.

Today, Barkerville consists of equal parts living museum, and stores and restaurants reminiscent of earlier days. In a dry-goods store, I overheard a woman in a bustled gown and ornate, feathery, hat say to the clerk, “I need to buy some yard goods,” and bolts of calico and gingham were proffered for inspection.

A couple of dapper gentlemen in vests and suspenders, with muttonchop sideburns sauntered past us, doffing their hats and greeting us with, “Good Day!”

As we entered a general store, my 12-year-old daughter, Kirsten, glanced around, then her eyes widened at row upon row of enormous glass jars filled with a rainbow of candies. The jawbreakers, in graduating sizes, were labeled “stupendous,” “almost ultimate” and “ultimate.” Suffice it to say that the “ultimate” would choke a horse, of which there were many here, carrying out daily tasks such as making deliveries and offering carriage rides.

Lace nightgowns, cast-iron pots and wooden utensils were on display, as well as bone China, fans and simple wooden toys. Everything in the store, as is true of pretty much everything in Barkerville, is representative of gold rush days. While I browsed, Kirsten picked up a folk toy, a tumble ladder, with a little character that swung from rung to rung. My digital-age daughter played with it the entire time we were in the store.

Farther along the boardwalk, I was surprised to come across a lively, packed Chinese restaurant, glowing red with layer upon layer of Victorian-era kitsch and strings of lanterns. The posted menu was filled with vintage foods such as chop suey (meat and vegetables in a starch-thickened sauce) and egg foo young, an omelette dish. A few storefronts down was a Chinese laundry, complete with signs in Chinese and English. It was then I realized that the town was divided into Caucasian and Chinese sections by gold rush era racial segregation.

The shops and dwellings in the Chinese section were fascinating. A dark, tea-colored store interior, a mini-museum, was filled with Chinese tea trade antiques, bundles of tea leaves and earthenware tea sets. A nearby boarding house showed the grimness of life for single Chinese men, with rows of bunk beds crowded like kernels on a corn cob, and a small wood stove, with nary a place to put their belongings. Obviously, there were few.

What seemed to us originally to be something we could take in, in oh, maybe a couple of hours, turned into a day of discovery. Every time we thought we were finished exploring, we stumbled across yet one more hidden-away attraction among the more than 125 restored or reconstructed buildings.

By the time my family was dragging and ready for ice cream and getting back on the road, I was still fascinated by the richness of this living museum experience.

Peering through the window of a clapboard one-room schoolhouse, I saw that “students,” — visitors, actually — were getting what appeared to be a historic classroom lecture from a strict-looking, bun-haired schoolmarm. I opened the door as quietly as possible, yet the teacher stopped talking and stared right at me. “Well, look who’s late!” she said. “I’m sorry, but you know my rules: Late to school, and you might as well stay home and help with the chores!”

Late or not, I’m glad I didn’t stay home.

If You Go

Barkerville Historic Town is open during the summer and during the month of December, when it swells with tours, demonstrations, street interpreters, live theater, restaurants, gift shops, a bakery, a photography studio and many more attractions.

www.barkerville.ca

British Columbia Tourism

www.hellobc.com

- How to Get Around in Sydney: A Local’s Guide to Traveling Around Sydney - April 24, 2024

- The Low-Key Magic of Ghent, Belgium - April 22, 2024

- Discover the Hidden Charm of Extremadura in Spain - April 20, 2024