As I stood beneath the cliffs of Scottsbluff National Monument in Nebraska, the very location where the pioneers of the Oregon Trail traversed, I couldn’t help but wonder what it was like to embark on such a treacherous journey. The mere idea of the Oregon Trail feels so alien in such a modern world, yet this very expedition forged the foundation of our existence in the West.

In the early 1800s, pioneers explored and carved the 2,170-mile path that hundreds of thousands of people would take in search of a better life. This not only came with tremendous risk, but it also resulted in the profound displacement and tragic loss of indigenous lives, a dark reality we must acknowledge.

Where the Oregon Trail Began

Independence, Missouri, a town perched on the banks of the Missouri River, played a crucial role as the launching point for the Oregon Trail. With a trading post packed with necessities and river access to the trailhead, it was the perfect place for travelers to start their six-month-long arduous journey. Here, you can visit the National Frontier Trails Museum to learn more about the starting point of the Oregon Trail.

After stocking up on supplies in Independence, pioneers crossed the Missouri River, cut through the northeast corner of Kansas and spent the next 486 miles trekking through Nebraska’s prairie. The first third of the Oregon Trail had flat, relatively manageable terrain with the main obstacles being storm-related. West Nebraska was where the terrain would become more three-dimensional, foreshadowing a challenging future crossing the Rocky Mountains.

The Emigrant Landmark, Chimney Rock

The most documented landmark on the Oregon Trail was Chimney Rock, a towering rock formation in West Nebraska that stood out from miles away. You can visit Chimney Rock and its dedicated museum, Chimney Rock Museum, to learn more about this spectacular formation. It is open seasonally from May to October.

Today, Chimney Rock stands 325 feet tall, but it used to be much taller during the height of the Oregon Trail in the 1800s. Erosion, weathering, and lightning have been shortening the spire over the years.

Read More: Exploring the Unexpected Beauty in Western Nebraska

The Trials and Tribulations of Traveling the Oregon Trail

During the peak of westward expansion between the 1840s and 1860s, it is estimated that hundreds of thousands of people took the Oregon Trail. Out of those, 10,000 – 30,000 people died along the way. So, what exactly were the risks and how did so many people die?

Disease was the number one killer of Oregon Trail pioneers. Cholera, dysentery, and smallpox were rampant and spread quickly between wagons. Malnutrition and starvation were also common due to sparse food supply and harsh conditions. Crossing rivers, prairies, and mountains always posed a risk, especially when the weather wasn’t cooperating.

Pioneers typically began their journey in the spring so that they could reach their destination before winter. Sometimes snowfall and storms came early, while other times there were delays within the journey itself. Throughout the journey, pioneers experienced scorching hot conditions that could lead to heatstroke, bitter blizzards that could lead to hypothermia and vicious bouts of thunderstorms that could destroy belongings and lives.

Lastly, there would be the occasional conflict with nearby Native American tribes that would often result in fatalities on both sides.

Oxen and Other Logistical Nightmares

Wagons pulled by oxen, also known as “prairie schooners” were the primary mode of transportation on the Oregon Trail. They could typically carry 2,000 to 2,500 pounds of supplies and fit four to six family members (including kids). Families tried to make 10-20 miles of progress per day. Of course, they took breaks to forage for food, do chores, and for the oxen to rest. Religious travelers would also rest on Sundays to observe Sabbath. Altogether it would take an average of four-six months to complete the journey.

The oxen, resilient animals known for their strength and endurance, were burdened with the most challenging part of the job – pulling the wagon. There only needed to be six to successfully pull nearly 3,000 pounds. Oxen were low-maintenance eaters and were generally satisfied grazing throughout the day as needed.

Sometimes people would opt to take mules or horses instead, but they’d need twice the amount which would be much more expensive. Oxen were generally slower and more stubborn than horses or mules and would not thrive when crossing rivers. These minor disadvantages didn’t sway the bulk of the travelers from choosing oxen to pull their wagons.

Oxen crossed prairies and easygoing terrain without needing shoes. As the terrain became more rocky and mountainous, they needed to be shoed to protect their hooves. Unlike horses, oxen have cloven hooves so they need eight shoe parts instead of four. They also don’t lift their feet like horses, so people had to invent a different shoeing process.

Shoeing an Ox 101

Step 1: Dig a big trench

Step 2: Tie ropes around the ox’s legs to keep them from running away

Step 3: Flip them on their back into the trench

Step 4: Place all eight shoe parts on their feet within 30 minutes before the weight of their body suffocates them

Crossing the Rocky Mountains

Early pioneers discovered the easiest way to cross the Rocky Mountains was through the South Pass, located in present-day Wyoming. The pass was gradual and open, unlike many other parts of the Rockies. Sometimes there would be scouts, mountain men, and guides who helped direct and aid pioneers through the pass.

Right before the pass, there is a town called Casper, where there is another museum dedicated to the Oregon Trail. The National Historic Trails Interpretive Center is filled with interactive exhibits that commemorate Native American history, early explorers, and Oregon Trail and its many offshoots. Admission to this museum is free.

If pioneers didn’t make it to South Pass or had to cross elsewhere, they would often have to make modifications to their wagons to cross steeper terrain. This included removing excess weight, reinforcing axles and wheels, and using ropes or chains to control the descent of the wagon on steep slopes. Sometimes pioneers would have to disassemble the wagons altogether if it became too unmanageable.

The Emigrant Trail

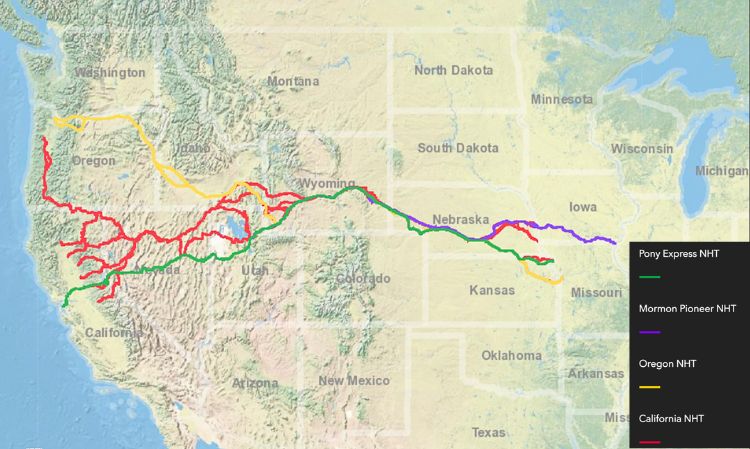

The term “Oregon Trail” generally refers to the journey from Missouri to Oregon. However, the trail’s significance extends beyond its main route. As westward migration increased in the mid-1800s, dozens of other offshoots were created including the California, Mormon, Bozemen, and Pony Express trails. This is collectively known as the Emigrant Trail. Check out this Interactive Map of the historical trails.

The End of the Oregon Trail

Once pioneers made it to their final destination (which varied depending on their reason for emigrating), they established homesteads, integrated with existing communities, and began economic endeavors. Those who settled in the Willamette Valley in Oregon were fortunate to have access to very fertile land, perfect for farming. Others got into trading, crafting, or developing new infrastructure. Check out the End of the Oregon Trail Interpretive & Visitor Information Center in Oregon City to learn more.

Reaching the end of the Oregon Trail marked the beginning of a new life for hundreds of thousands of people. By 1859, Oregon had reached a population sufficient enough to be admitted as the 33rd state of the United States.

Read More: Traveling the Oregon Trail in the Time of COVID

This All Came with a Cost

Westward expansion undoubtedly caused tremendous harm to Native American communities. Indigenous people suffered from disease, displacement, and land loss. Forced assimilation significantly eroded their culture and lifestyle. When learning about the Oregon Trail, it is crucial to acknowledge the horrors imposed on native communities.

There are still many native tribes that have survived and are prospering today. Many have been able to preserve their culture and integrate with the contemporary world. Visit the Tamástslikt Cultural Institute in Pendleton to learn about the Oregon Trail from the native point of view. There are interactive displays that celebrate the customs of the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla tribes. In addition to the history, you’ll learn about how these vibrant communities are thriving and contributing to today’s world. There is also an exhibit called “We Will Be” that highlights both dreams and concerns for the future.

If you want to plan a trip around the Oregon Trail, here is a fantastic Interactive Map that shows all the wonderful museums, interpretive centers, and historical sites along the way. Although specific to the California Trail, most of the map generally aligns with the Oregon Trail.

Read More

- A Guide to Tulip Time in Holland, Michigan - April 8, 2024

- Why Airalo is My Go-To eSim When Traveling Abroad - February 6, 2024

- NOAD, the Digital Nomad’s Dream Housing Swap Service - February 2, 2024