Go World Travel is reader-supported and may earn a commission from purchases made through links in this piece.

I knew I was being reeled in but let it happen. I was enjoying watching the wily souk merchant reach deep into his bag of sales tools: regale me with stories about his products, pop open containers to wave the aromas under my nose, spoon out cedar-tree honey to sample, pour me tea, offer dates, even a water bottle.

I’d planned to buy some teas and spices anyway, so why not from affable Josem. Besides, I wanted to get in the legendary spirit of Mutrah, the beating heart of historic Oman.

Best Tips & Tools to Plan Your Trip

A Legendary Trading Empire

Oman once reigned over a legendary trading empire stretching from Arabia and the Middle East to East Africa and South Asia. Mutrah was its greatest port, welcoming camel caravans from the desert and sailing vessels from many seas laden with frankincense, spices, gold and carpets.

Today, the old houses of merchants who grew rich from the trade line Mutrah’s picturesque Corniche, the boardwalk that hugs the bay. And their trading hub, the souk, or marketplace, remains one of the great marketplaces of the region, where everything under the Omani sun can be found.

The Souk Is an Explosion of Color

Deep on a tiny lane in the sprawling covered Mutrah Souk, Josem’s shop was an explosion of color – countless containers brimming with pungent herbs and spices, from blue lavender and pomegranate flowers to saffron, cardamom pods and whole nutmeg.

“Mutrah is an ideal place to live and do business,” Josem told me. “There are people here from many countries and all are welcome and part of the community.”

At the end of the Corniche is Mutrah Fort, built on a craggy promontory by the Portuguese in the 1580s It is one of some 500 forts in Oman – a bonanza for aficionados of climbing ramparts. Many have been restored, some might say too exuberantly: they were never so pretty and flawless, even when first built.

Safe, Clean and Organized

But that is surprising Oman in a nutshell: the country is safe, clean and organized, from the perfectly surfaced and striped roads to the impeccably dressed populace.

Most men are in spotless white dishdasha robes with embroidered hats and neatly trimmed beards, the women in head-to-toe black abaya, often of exquisite fabric with a designer purse, some are veiled.

Crime is almost non-existent, and the Omanis are welcoming and helpful. More than once I was spontaneously offered Arabic coffee and dates, the traditional gesture of hospitality here.

An Old-World Look and Feel

With oil and gas revenue, Oman modernized over recent decades.

But unlike the Gulf States next door that have become ultra-modern, high-rise super cities, by decree of the Sultan (beloved because he is perceived as caring about and taking care of his people), Oman took a different, culturally protective route: low-rise construction that retains elements of Arabian architecture and white-to-ecru colors.

The result: modern Oman still has a somewhat old-world look and feel.

The abandoned village of Manah is a rare and fascinating remnant of the fast-fading historic Oman. As the country grew more affluent, the age-old mud-brick homes ‒ that lacked running water, indoor plumbing and other amenities – were being abandoned, torn down and replaced with new construction.

To walk Manah’s maze of dirt lanes, amid the crumbling buildings and falling archways, is a step back in time, reminiscent of a Western ghost town. Some renovation is taking place in one section to turn the village into a historical heritage and tourist site.

A Fort and Castle Anchor Nizwa Oasis

A short drive from Manah is the oasis town of Nizwa, one of the country’s most popular destinations, especially for Omani families. The anchor is the Nizwa Fort and Castle adjacent to a sprawling souk. The large interactive complex explains and depicts the gamut of Omani culture and history with sophisticated displays, exhibits and information boards.

There are tents filled with handicrafts for sale and Omani foods being prepared for visitors to sample, such as mishkak meat skewers cooked on wood-burning grills and paper-thin, crepe-like snacks slathered with date syrup.

Imposing entry gates, high walls and rows of porticos, reconstructed and expanded from the original marketplace, dramatically house the souk. The bustling scene of haggling and buying – gold, jewelry, dates, sweets, antiques, spices, etc.‒ is complemented by restaurants, boutiques, tea rooms and even ice cream parlors catering to the crowds of visitors.

Fearsome Natural Beauty of the Interior

While Nizwa and Mutrah are popular spots, Oman’s wild wadis – and the imposing and fearsome natural beauty of the interior ‒ in particular draw foreign visitors. Oman’s numerous wadis – river beds, ravines and narrow channels between mountains that normally are dry ‒ become raging and often destructive torrents when heavy rains arrive, usually in summer.

On a 4×4 trip into the Wadi Bani Awf region, we were repeatedly reminded of the unstoppable force of nature: piles of rock, tree trunks and natural debris that were carried down wadis by the water, taking out roads, bridges and occasionally houses.

The wadis wend through daunting and indomitable mountains, sheer walls of black rock and shale soaring up to rugged peaks. One moment they were obscured in shadows, rows of menacing crags echoing the spine of a dinosaur, and the next the sun’s rays sneaking through the clouds painted the massive sierras in orange and yellow hues.

Hair-Raising Precipices Tumble 100s, Even 1000s of Feet

We drove steep and rocky tracks through the mountains often negotiating a hair-raising precipice on one side ‒ tumbling down hundreds, even thousands of feet.

Hiking in the wadis nicknamed Snake Canyon and Little Snake Canyon (because of their serpentine courses), took my breath away.

We plied the narrow, rocky passageways that wind between towering mountains, where nature has colored the high walls, stones and boulders in a bold palate of colors: grays, purples, blues and browns. We swam in deep pools of dark green water shrouded in shadows.

True Omani Hospitality

And then, invoking true Omani hospitality, Bader, my guide, pulled out a thermos and dates as we sat by a pool in Little Snake Canyon. He poured us Arabic coffee that channeled the souk: “Omanis like to share spiced coffee with friends. I added rose water, cardamom and a little saffron,” he beamed.

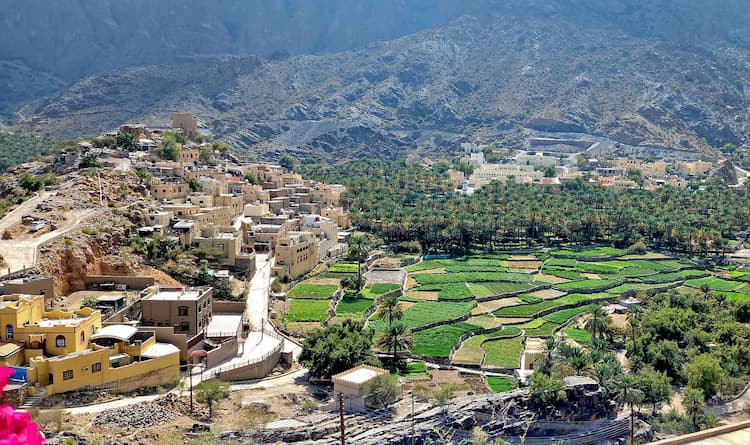

Amid these barren, harrowing mountains is a true desert oasis, Salad Byt, a bucolic village clinging to a promontory topped by an ancient fort.

We walked among verdant vegetable gardens and date palm orchards, the quiet broken by the sound of spring water pouring out from underground and traversing irrigation canals. Using long ropes, workers were climbing palms to pollinate them by hand.

Sailing the Spectacular ‘Fjords of Oman’

While the cold, dark wadi pools brought shivers, the waters of the “Fjords of Oman” were warm and translucent. Musandam, the most northerly of Oman’s 11 governorates at the Strait of Hormuz, the Persian Gulf’s infamous oil choke point, harbors spectacular fjord-like inlets called rias.

We sailed from the Arabian Sea up the calm, sheltered waterways of Khawr Ash Sham ria under high rock walls rising hundreds of feet.

Tiny fishing villages dotted the shoreline, tucked between vertical mountains crashing into the sea. The dry, barren topography exposed layers of strata, in swirls and waves, one color atop another – yellows, oranges, browns, reds and ochres – marking off geological time.

We landed on Telegraph Island to snorkel in the clear green water teeming with silver, blue and yellow cichlids, and to explore the ruins of a British facility: in the mid-1800s the island was an important station in a short-lived high-tech breakthrough of the time, the telegraph cable laid from India to England.

Dolphins Raced Our Boat Back to Port

On the way to Khawr Ash Sham inlet, dolphins appeared and briefly swam alongside before losing interest. On the return, however, at the same spot, the dolphins became serious competitors: the captain cranked up the speed and the playful mammals raced us most of the way back to port.

The boat into Musandam’s ria was a motorized version of the traditional Arab sailing vessel, the dhow, that in the olden trading days was called at Mutrah port laden with goods from many lands. Dhows are still being constructed today, at the historic shipbuilding yards of Sur.

After stopping for a swim at Bimmah Sinkhole – a deep pit carved out by nature with warm turquoise water and limestone walls that is a popular bathing spot ‒ I arrived at a charming port of white-washed buildings.

Sur is set around a large lagoon and a long seafront Corniche. Volcano-shaped promontories each topped with a small fort and a tall, iconic lighthouse on a point punctuate the evocative panoramas.

A Golden Era of Omani Shipbuilding

While Oman has been designing boats and engaging in maritime commerce for millennia, the golden era of Omani shipbuilding was the 1700s and 1800s, with the addition of breakthrough new materials and techniques. And they are still at work.

In the shipbuilding yards of Sur (which, by the way, claims Sinbad the Sailor as a native son), I watched artisans, sitting inside a 100-foot-long ribbed hull, cutting and shaping wood with axes and chisels. It takes some six months to a year to build a vessel ‒ all by hand and without plans. The work is done from memory, eyeballing and figuring as they go along.

The dhows that still ply the coastal waters here remain a link between Oman’s glorious past and a modern present that beckons travelers to visit this welcoming and historic land.

Inspire your next adventure with our articles below:

Author Bio: Freelance writer/photographer Edward Placidi discovered his passion for exploring the world ‒ and sampling its foods ‒ as a teenager and has rambled to the far corners of the planet, leaving behind footprints in 122 countries (so far). He has contributed articles and photographs to scores of newspapers, magazines and websites. When not traveling, he is whipping up delicious dishes inspired by his Tuscan grandmother who taught him to cook, with as many ingredients as possible coming from his vegetable and herb garden.

- Together at Sea: A Mediterranean Family Adventure - April 27, 2024

- Travel Guide to Colorado - April 26, 2024

- Travel Guide to Croatia - April 26, 2024