Go World Travel is reader-supported and may earn a commission from purchases made through links in this piece.

Those who make the trip down into Canyon de Chelly will often tell you it is one of the most memorable experiences in their lives. This natural wonder with its mesmerizing scenery and rich history is a Southwest gem.

Where Is This Unique Site and How Do You Pronounce Its Name?

Located in northeastern Arizona within the boundaries of the vast Navajo Nation, Canyon de Chelly is an 84,000-acre archeological sanctuary administered jointly by the National Park Service and the Navajo people.

It was designated a National Monument in 1931 to protect and preserve the numerous archeological resources long known to exist on the canyon rims, walls and bottomlands.

The name was derived from the misspelling and mispronunciation of the Navajo word for the canyon, “Tseyi,” which is pronounced “say-ee.” Over time, the word became “de Chelly,” which is pronounced as “de-shay.”

Best Tips & Tools to Plan Your Trip

Geological Facts

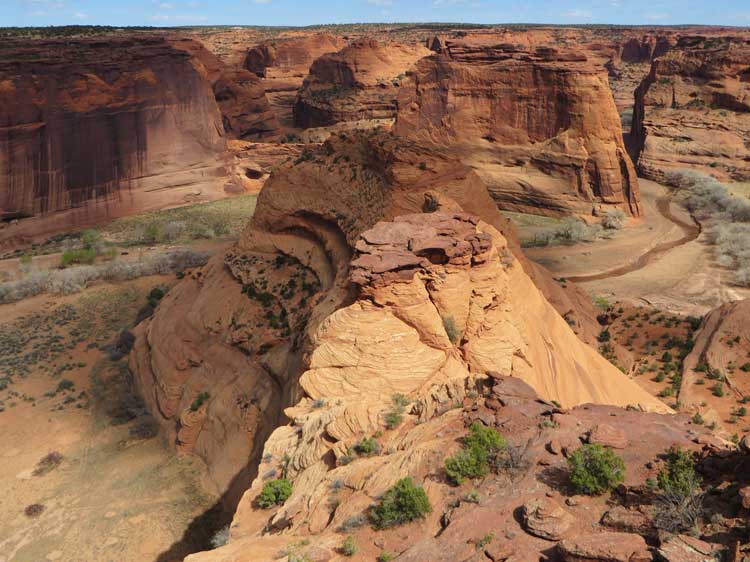

The canyon, which is actually a labyrinth of several canyons, is composed of sandstone and was created millions of years ago. Land uplifts and stream cutting formed the colorful sheer cliff walls that give the place its unique beauty.

The cliffs rise dramatically, standing in some places over 1,000 feet above the canyon floor. Though they make access to the canyon bottom difficult, they have long been viewed as an advantage, providing protection for both ancient and modern Native Americans throughout the centuries.

Human History in Canyon de Chelly

Natural water sources and an ideal soil composition provided a hospitable environment for flora and fauna to exist within the canyon, which eventually attracted the first human inhabitants to the area. The Ancient Pueblo people, or Anasazi as they are often referred to, found the canyons an ideal place to plant crops and raise families.

They built multi-storied villages, small household compounds and kivas that dot the canyon alcoves and talus slopes. Their cliff dwellings took advantage of the sunlight and allowed for a natural system of heating and cooling.

They also provided a natural form of protection, which was enhanced by the addition of accessible ladders that could be lifted during enemy attacks.

Thanks to an arid climate and the shelter of the overhangs and caves, a number of the structures, along with other artifacts and organic remains, have been preserved. Of the total 2,700 ruins discovered in the canyon, 700 are still in some form of existence today.

The Anasazi thrived in the canyon until the mid-1300s when they left the area to seek better farmlands. This paved the way for the Hopi, descendants of the Anasazi, to migrate into the area.

Though they had their fields of corn and fruit orchards within the canyon, the Hopi did not winter there, preferring to settle instead on the mesa tops.

The Settlement of the Navajo

In the 1700s, the Navajo settled in the Southwest and became residents of the canyon, where they continue to remain today. It is both the physical and spiritual home of the people.

The Navajo are related to the Athabaskan people of Northern Canada and Alaska. Like the “Ancient Ones,” they still plant their crops, raise livestock and build their hogans on the canyon floor. Roughly forty to fifty families currently live within the park borders.

It is unclear as to when the Europeans first became aware of this area but a 1776 Spanish map includes the location of Canyon de Chelly. Soon after, Spanish troops entered the region and subjugated the Navajos. Pictographs on rock walls depict this event, providing evidence of its occurrence.

Later, there were American military explorations and war campaigns against the Navajo and a history of rampant injustices ensued.

Archeological Finds in Canyon de Chelly

In 1849, James H. Simpson of the Corps of Topographical Engineers began recording several individual archeological finds in the canyon. This includes one he deemed Casa Blanca or White House because of a white-plastered room in its upper portion.

Simpson is credited with noting similarities between the construction methods used in this region and those utilized in the pueblo ruins at New Mexico’s Chaco Canyon, 75 miles to the east.

You can get spectacular views of the canyon from its numerous overlooks on the North and South Rim Drives. A small part of the canyon is accessible via the 2.5-mile White House Trail, the only public trail there.

The switchback path leads you down 600 feet to the famed White House Ruin. No fee, permit or guide is required for either of these endeavors. Currently, however, the trail and White House Overlook are closed due to safety and law enforcement concerns.

Enlist the Services of a Navajo Guide to Tour Canyon de Chelly

To truly experience this vast arena, however, you need to spend time inside its walls traveling via vehicle, horseback or foot while in the accompaniment of an authorized Navajo guide.

There are a number of companies that offer guided services. Among them is the highly regarded Antelope House Tours, which is known for its knowledgeable and dedicated guides. Our group’s guide picked us up in his trusty, road-weary Suburban and proceeded to drive us down into the canyon.

He navigated the shallow rivers, thick mud and soft banks that often make travel within the gorge challenging. At times it appeared as if we might not make it any further due to the unstable conditions.

However, he remained calm and collected and never failed to get us to the next juncture. Even when a younger guide in another vehicle said he wasn’t able to make it all the way to Mummy Cave, our guide seemed undaunted and continued ahead.

Upon arriving at the obstacle in question, he appraised the situation, smiled and then put the pedal to the medal as we cheered him onward. It was obvious nothing was going to stop our guide from getting us to one of the largest ancestral Puebloan villages in the canyon and a definite highlight of the tour.

Must-See Mummy Cave

People who migrated from Mesa Verde built Mummy Cave in the 1280s. Its massive tower complex rests on a ledge with east and west alcoves that are comprised of living and ceremonial rooms.

It was clear our guide lived and breathed his culture and the canyon. He often spoke about the place with awe and reverence. Though he has resided in the area his whole life, it still remains special to him and he never tires of sharing it with visitors.

He regaled our group with the geology and history of the canyon and its people. He explained the meanings of the many petroglyphs and pictographs that decorated the rock walls.

Additionally, he provided us with much information about the various plants and wildlife that make their home in the canyon.

At various times during the tour, we got out of the car to obtain a closer look at the archeological remains. We also took a hike to experience the surroundings in a different way. On foot, the canyon’s rust-colored rock walls appeared as towering sentries, standing watch over a castle’s jewels. Imposing and grand, these giant monoliths made us humans feel very small and insignificant.

Tragedies at Massacre Cave and Fortress Rock

Several landmarks have sad and disturbing histories. Massacre Cave, for example, refers to the Navajo killed there in the winter of 1805 by a Spanish military expedition. About 115 Navajo took shelter on the ledge above the canyon floor. Soldiers eventually found and massacred them.

Another, Fortress Rock, was the scene of a stand-off between the Navajo and the Indian fighter Kit Carson in 1863. The Navajo had sought refuge at the top of the rock, after stockpiling dried food inside storage bins built of stone and mud.

Carson’s troops set fire to all the abandoned Navajo homes they could find. They destroyed food supplies and filled up water holes with dirt. The Navajo realized they would not survive the winter and eventually came down from the rock to surrender. Then, they began a forced several hundred-mile trek to Fort Sumner. Their infamous death march became known as the Navajo Long Walk.

There is much to learn from Canyon de Chelly and having an experienced and knowledgeable Navajo guide helped make history come alive for our group. His invaluable insights gave us a unique perspective while deepening and personalizing our experience.

If You Go:

For Information about Canyon de Chelly: www.nps.gov/cach

Antelope House Tours: www.canyondechelly.net

Author Bio: Debbie Stone is an established travel writer and columnist, who crosses the globe in search of unique destinations and experiences to share with her readers and listeners. She’s an avid explorer who welcomes new opportunities to increase awareness and enthusiasm for places, culture, food, history, nature, outdoor adventure, wellness and more. Her travels have taken her to nearly 100 countries spanning all seven continents, and her stories appear in numerous print and digital publications.

- Travel Guide to Colorado - April 26, 2024

- Travel Guide to Croatia - April 26, 2024

- Top 10 Things to Do in Ireland - April 25, 2024