The turndown service at many upscale hotels in Scotland is extra special. No chocolates here. A tiny bottle of whisky – to the Scots, it’s whisky, not whiskey – is left on your pillow. In finer hotels, such as Edinburgh’s iconic Balmoral, your drink (always malt) will be delivered in a lovely carafe along with a small pitcher of water and a crystal glass.

“Whisky will revive you, give you energy,” we are told soon after we arrive at the Hilton Dunkeld House Hotel. “And will take the chill off a damp day.”

That’s the truth, even in the morning. At Dunkeld House, an hour’s drive from the capital, it’s available at breakfast – a wee dram for the porridge.

There are hundreds of malt whiskies available in this country. The differences are subtle; it takes time and talent to learn. The place to start is, of course, at the source – the whisky trail of Speyside.

The area is referred to as the Malt Whisky Capital. The question: is it the whisky capital of Scotland or the whisky capital of the world?

“Same thing,” says bus driver Andrew Huntly. “There are 27 distilleries within a 30-mile radius using water from the River Spey,” he adds.

At the Glenfiddich distillery at Dufftown, visitor center manager Brian Robinson can tell you everything you’ve ever wanted to know about whisky.

Glenfiddich is one of the few independent family distilleries still operating in Scotland. It was founded in 1886 by William Grant and is now headed by Peter Grant Gordon, a fifth-generation member of the family.

Many staff members are long serving; 20 have been working more than 30 years with the company. When the coppersmith, Dennis McBain, retires at age 66, he will have been at the distillery 50 years.

“The family has people here. Computers do not rule supreme here,” says Robinson. “We produce a lot but we’re not mass produced. We have a commitment to craftsman; our dependence on computers is minimal.”

There are only three ingredients needed for whisky – water, yeast and barley. For Glenfiddich, it’s Robbie Dhu (Gaelic for “Black Robert”) spring water from the nearby Conval Hills.

During a tour of the facility, Robinson explains the process step by step: malting (barley is “malted” to convert the starch into soluble, fermentable sugars); mashing (malted barley is ground and mixed with spring water); fermentation (yeast is added to liquid from the mashing process and converts the natural sugars to alcohol); distillation, maturation and bottling.

Glenfiddich is the only Highland single malt to be bottled at its own distillery.

“We make it slowly,” says Robinson. “If you’re going to rush it, you’re missing the point. A slow ferment gives flavor and character.”

The firm’s commitment to excellence is not confined to whisky. It also sponsors an artist-in-residence program. Each artist stays two to three months in a house on the property. Artists from across the world are welcomed.

“The idea is we’re bringing them into an environment [with which] they are unfamiliar, so there is new inspiration,” explains Robinson. “Whisky-themed? Great. But if not, that’s the risk we take. It’s not very fair on an artist to invite them in and then give them boundaries.”

“We get pieces like the [small bronze sculpture] Angel’s Share in Warehouse No.1. We get things like The Fence, which is next to the house the artists stay in. It’s just recycled plastic tied to a fence [but] I’m sure there’s a deeper meaning than that,” he laughs.

“They typically leave a piece for us as a thank you, but there’s no obligation,” he says.

Regular tours of the Glenfiddich distillery are free but if you want the “Connoisseur” treatment, which includes tastings, there is a $40 fee. Tours can be conducted in 10 languages, including sign languages.

During our tasting, Robinson tells us it’s perfectly alright to add water to malt whisky. There’s no right or wrong way to drink it, he says, though there are purists who insist whisky neat is the only way to drink it.

Ted McIntosh of Bayfield, Ontario, agrees with Robinson about the water. “Just a wee thread – one or two drops. It releases the serpents,” he says.

Whisky aficionado McIntosh and his wife, chef and cookbook author Kathleen Sloan-McIntosh, own the Black Dog Village Pub and Bistro where they regularly hold whisky tastings. They recently spent a three-week vacation at Craigellachie, a 10-minute drive from Glenfiddich.

The Speyside Cooperage, the only working cooperage in Britain, is located at Craigellachie, where you can see how whisky casks are made and repaired (admission is $6.50 U.S. or $17 per family) and learn the importance of the cask to the making of fine whisky.

“A distiller uses barrels like a chef uses spices,” says McIntosh. “The barrel is a huge factor.” Like the Glenfiddich distillery, the Cooperage is a family-owned business, which has been run by three generations of the Taylor family since 1947.

From a viewing gallery that overlooks the shop floor, you can watch the traditional methods of coopering that are still used today. Only oak is used to produce the casks that hold quality wines and liquor. That’s because it prevents seepage and allows the contents to breathe without spoiling the flavor. Most of it is white oak that comes from the United States.

“Different oaks breathe differently,” explains McIntosh. “With the first fill (barrels are used several times) there is more contact with the oak,” thus affecting the color and flavor of the whisky. “These days the first fill is usually Madeira.”

Coopering is a highly-skilled trade with a five-year apprenticeship overseen by experienced journeymen. “There are two young people at the moment who are at different stages. “[All training] is done on site and there’s a job for them once they’re finished,” explains Ronnie Grant, a former cooper who has worked here for 33 years. His father and brother are coopers, as well.

It’s a piecework system where each man makes or repairs an entire cask and is paid per cask. “Today’s cask is a hogshead. It’s a middle size, about 55 gallons,” says Grant.

There are various sizes in addition to the hogshead: a butt is 500 liters (132 gallons); a barrel is 180 liters (48 gallons); a puncheon is 500 liters (132 gallons). “A barrel is American, a butt is Spanish,” Grant says. “The American barrel is by far the most popular size.”

There are no metal screws or nails in the casks. “Each cooper puts his personal stamp on a barrel and if there’s any problem it’s sent back to the cooper to make it right but he’s paid only once,” says Grant.

That being the case, he’ll probably get it right the first time.

It was their appreciation of the craft and of the whisky that brought McIntosh and McIntosh-Sloan to Speyside and Craighellachie – to visit the Cooperage but to also taste a wee dram or two or three.

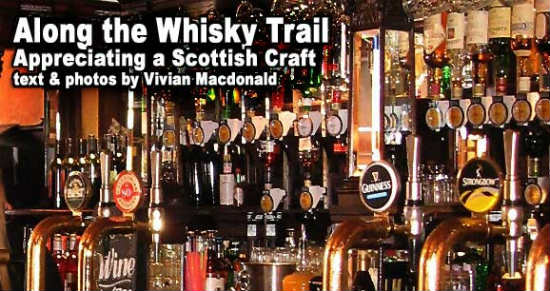

At the Craigellachie Hotel, there are nearly 700 single malt whiskies available; at the Highlander Inn Hotel, there are 180 malt whiskies on offer.

“We didn’t try them all,” laughs McIntosh.

If You Go

Glendfiddich

Speyside Cooperage

www.speysidecooperage.co

Scottish Tourist Board

Vivian Macdonald is a freelance writer based in Stratford, Ontario. To view more of her work, visit <arel=”nofollow” href=”https://www.viviansvoyages.com”>www.viviansvoyages.com.

- Top 10 Things to Do in Ireland - April 25, 2024

- How to Get Around in Sydney: A Local’s Guide to Traveling Around Sydney - April 24, 2024

- The Low-Key Magic of Ghent, Belgium - April 22, 2024