The Da Vinci Code is both blessing and curse to the staff and leadership of London’s Westminster Abbey. Readers of the best-selling novel by Dan Brown have besieged the Abbey since the book’s publication in 2003. With the May 2006 release of the movie, staring Tom Hanks and Audrey Tautou, a new onslaught of Da Vinci Code tourists seems inevitable.

Controversial since its publication, The Da Vinci Code postulates a Catholic Church conspiracy to hide the “fact” that Jesus had children by Mary Magdalene. The novel is a page-turning thriller, mixing religious history, theory and fiction. The Da Vinci Code spins a web of intrigue, secret societies and murder around a modern-day quest for the Holy Grail.

In 2004, Reverend Nicholas Sagovsky, Westminster Abbey’s canon theologian, took to the pulpit and attacked the book as “complete and utter rubbish,” perhaps forgetting that “rubbish” can be a key ingredient in popular fiction. However, Reverend Sagovsky acknowledged the harmless fun of The Da Vinci Code with the hope that those who come to the Abbey seeking the Code may learn about “authentic Christianity” through osmosis.

By early 2005, in round two of the Abbey versus the novelist, Westminster officials provided a fact sheet to their tour guides so they could set the record straight when queried about the book.

Despite condemning the novel on theological grounds, the Abbey’s fact sheet was remarkably light in terms of actual contested facts.

The Da Vinci Code states that the Abbey operates metal detectors for security. “Not true,” says the Abbey. The novel claims that 18th century poet Alexander Pope delivered the eulogy at Sir Isaac Newton’s funeral in the Abbey. Also untrue, according to the fact sheet.

And just try making a copy of a brass grave marker in the Abbey, as Dan Brown’s bestseller describes. “Brass rubbings are not allowed,” warns the Abbey.

Round three of the Abbey versus The Da Vinci Codecame when moviemakers sought to film inside the historic church. Negotiations were under way when Westminster Abbey’s leaders balked and the filmmakers relocated to another ancient cathedral, in Lincoln, England.

Refusing permission to film seems consistent with the Abbey’s earlier statements, but that didn’t stop Sir Ian McKellen, who plays historian Sir Leigh Teabing in the movie, from speculating about the Abbey’s hidden motives. On his Website, Sir Ian surmises “As no explanation for this reversal has been forthcoming, dark rumors worthy of Dan Brown’s own imagination have been whispered abroad.”

Ahhh … movie hype. Westminster Abbey, unlike most Anglican churches and cathedrals, is under the direct control of England’s monarch. Actor Ian McKellen adds his own conspiracy theory — that the Queen kept movie cameras out of Westminster Abbey during the filming of The Da Vinci Code.

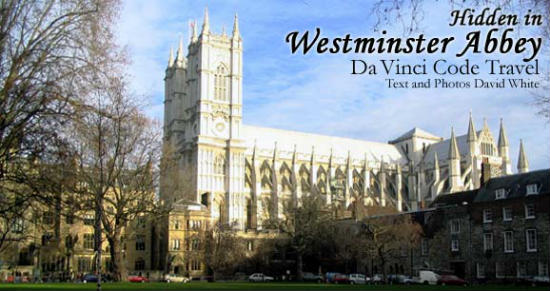

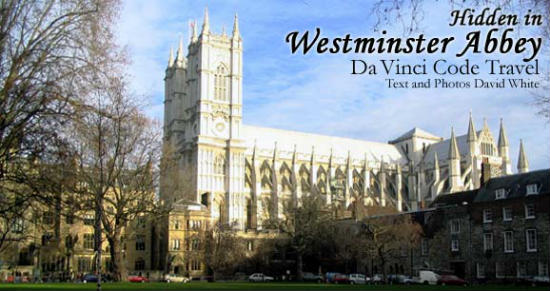

Originally the abbey church of a Benedictine monastery, which closed in 1539, Westminster Abbey is one of England’s most important Gothic structures and a national shrine. Its official name is t he Collegiate Church of St. Peter, but this name is rarely used.

Situated west of the Palace of Westminster, Westminster Abbey is the traditional coronation site for English monarchs. It was originally home to a Norman monestary, of which there are little or no traces left. The Abbey standing today was built by King Edward the Confessor around 1050, and was consecrated in 1065.

The ancient Abbey is filled with monuments and tombs, including that of Sir Isaac Newton, whose grave plays a minor part in The Da Vinci Code. Any Abbey visitor is free to seek out what the book refers to as this tomb of “a knight a Pope interred.” Feel free to remember, or ignore, the fact that Alexander Pope (“a Pope”) didn’t really read the eulogy at the funeral of the great scientist.

Having gawked at Sir Isaac’s final resting place, Da Vinci Code fans make their way to the Abbey’s octagonal Chapter House, site of a dramatic showdown in the book. The Chapter House is where Robert Langdon, the book’s heroic main character, tosses a cryptex cylinder toward the ceiling when evil Sir Teabing threatens to shoot co-hero Sophie Neveu.

The scene is pure fiction, but an event that did happen here had tremendous historical significance. In 1257, the King’s Council met in the Chapter House. The Council was the precursor to the English Parliament, and from it sprang a lineage that can be traced forward all the way to the United States Congress and other modern legislatures, worldwide.

Before heading off to find other book and movie sights in London — and there are many — visitors to Westminster Abbey should set aside The Da Vinci Code and seek out some of the other hidden gems of the Abbey, many of which don’t appear in Dan Brown’s novel.

Much of the Abbey is open to, and sometimes overrun with, tourists. Long before The Da Vinci Code, the Abbey was forced to institute a program to “restore the calm” to the sanctuary so that worshipers could, in fact, worship despite the din of touring crowds. A guided verger’s tour of the Abbey is one way for visitors to sample some of the church’s long history without aimlessly wandering the huge complex.

But much still lies hidden behind the scenes at Westminster Abbey. The Abbey’s library and muniment (document) room are not on the usual tour route. Up a narrow staircase off the east cloister, the library’s reading room is open to the public weekdays during limited hours.

With an appointment and appropriate credentials, serious scholars can review the collection of historic manuscripts and documents, many of which are — you guessed it — hidden from public view.

With an Abbey official as my guide, I went on a private tour behind closed doors in the library and found myself in a dark, dusty balcony room overlooking the sanctuary. We were surrounded by document cases, stacks of uncataloged historic papers, paintings and a large, ancient chest. That chest looks old enough … wonder what’s inside?

Apparently not the Holy Grail sought by the characters in The Da Vinci Code. And it’s a good thing, given the seeming lack of sophisticated theft or fire-protection systems in this nook of the Abbey. So it seems the library and muniment room have nothing to do withThe Da Vinci Code. But wait. Open the book and re-read Dan Brown’s acknowledgement.

“For their generous assistance in the research of this book, I would like to acknowledge the Louvre Museum, the French Ministry of Culture … the Muniment Collection at Westminster Abbey …”

Holy conspiracy! Will the hidden mysteries never end? Maybe not, based on a recent archeological survey. Archeologists used ground-penetrating radar to explore the area below the Abbey’s Cosmati pavement — the ornate mosaic floor located in front of the high altar. The more they looked, the more hidden mysteries unfolded, and the survey was expanded to reveal a series of previously unknown vaults and burial chambers that are still being examined.

A word about burials in Westminster Abbey. The dead are almost everywhere underfoot. The Abbey staff estimates that about 3,300 people are buried here, but that’s just a guess. Sir Isaac Newton is hardly alone here among famous dead folk. Kings and queens abound, including some of the most famous names in English history.

But there are also famous actors (Laurence Olivier), musicians (George Frideric Handel), and a large contingent of writers. The latter group includes Geoffrey Chaucer, Charles Dickens, Robert Browning, Alfred Lord Tennyson and Rudyard Kipling. Given the Abbey’s theological issues with The Da Vinci Code, Dan Brown probably won’t ever join this particular dead writer’s society.

Not every monument or hidden mystery in Westminster Abbey is ancient or even mysterious. On the way to view the private Jerusalem Chamber, we walked over a monument that official Abbey guidebooks generally ignore.

Thomas Crapper — the unfortunately named plumber, who, contrary to urban legend did not invent, but put much effort into popularizing, the modern toilet — was employed here in the late 1800s to install plumbing fixtures in the Abbey. Several manhole covers bearing the inscription T.CRAPPER & CO. remain today in Westminster Abbey.

Hidden from view, or at least closed to the public, the Jerusalem Chamber is an ornate room in the Abbey’s Deanery. Now used by the Dean of Westminster Abbey for meetings and official functions, the room was constructed in the 1300s as an add-on to the abbot’s quarters.

History records that in 1413 King Henry IV suffered a stroke while praying in the Abbey’s sanctuary. When the confused and dying King was carried into this room, he asked, “Where am I?” His minions replied: “Jerusalem, Sire.” King Henry knew he was doomed. His death had been prophesied — in the city of Jerusalem.

Dan Brown is not the first author to incorporate Westminster Abbey into his writing. Like Brown, William Shakespeare liberally mixed history with fiction. In his play Henry IV, the Bard adds a sinister twist to the historical record. In Shakespeare’s version, young Prince Henry just can’t wait to be king and tries on the crown as his father lies dying in the Jerusalem Chamber.

The Da Vinci Code controversy is a mere ripple in the thousand-year history of Westminster Abbey. The Abbey continues to draw faithful worshipers — and curious movie fans.

If You Go

Da Vinci Code locations in London:

Westminster Abbey

Open to the public, with self-paced and guided tours every day except Sunday. The church may be closed occasionally for special services and events. www.westminster-abbey.org

King’s College

Home to religious research libraries used by Da Vinci Code characters in their quest to find the Holy Grail. The libraries are generally not open to the public. King’s College buildings are scattered throughout central London.

St. James’s Park

The shadowy character The Teacher kills Teabing’s chauffeur here with a drink of poisoned cognac. Any sinister connections are belied by a walk through one of London’s most lovely (and safe) parks. The park is located between Buckingham Palace and Whitehall.

www.royalparks.gov.uk

Opus Dei

The real-life conservative Catholic organization has offices in London, but these are not open to the public.

National Gallery

Houses Leonardo Da Vinci’s Virgin of the Rocks painting, which plays a minor role in the book. The gallery is located on the north side of Trafalgar Square. Open daily 10 a.m. – 6 p.m; Wednesdays 10 a.m. – 9 p.m. Closed January 1 and December 24-26.

Quietest times are early weekday mornings and 6 – 9 p.m. Wednesdays. www.nationalgallery.org.uk

Fleet Street

Robert Langdon and crew race down this rather nondescript road on their way to Temple Church. The area was once home to London’s newspapers, most of which have now moved away from Fleet Street.

Temple Church

Site of one of several dead ends that The Da Vinci Code characters encounter before visiting Westminster Abbey. Unlike the Abbey, Temple Church seems to have embraced The Da Vinci Code. On Fridays at 1:00 p.m., the Master of the Temple gives a talk on the subject. Temple Church is located just south of Fleet Street. www.templechurch.com

- How to Get Around in Sydney: A Local’s Guide to Traveling Around Sydney - April 24, 2024

- The Low-Key Magic of Ghent, Belgium - April 22, 2024

- Discover the Hidden Charm of Extremadura in Spain - April 20, 2024