On Sept. 7, 1876, six of the most notorious outlaws in America rode their horses over an iron bridge and entered Northfield, a quiet little country town in Minnesota, a north-central American state bordering Manitoba and Ontario, Canada.

At the same time, two more bandits rode into town from the south. All of them wore long, white linen coats to hide the fact they were carrying revolvers and cartridge belts. They were desperate men, killers, bank and train robbers, Southerners, and former bushwhackers from the Civil War. They came to Minnesota because, in 1876, no one would suspect this type of outlaw military raid on an out-of-the-way farming town so far north.

The attack had been planned in great detail. Jesse James, Jim Younger and Bill Stiles hitched their horses in the town square, where they could cover the outlaws’ escape route back over the bridge.

Cole Younger and Clell Miller got off their mounts on the main street and pretended to be adjusting saddles, while they surveyed pedestrians and kept a lookout. Frank James, Bob Younger and Charlie Pitts tied up their horses on Division Street and strolled casually into the First National Bank. It was 2 p.m. and the most famous bank robbery in American history was about to begin.

A Visit to Northfield, Minnesota Today

The clock that hung in the bank that day in 1876 is still there. It still reads 2 p.m. In a “Twilight Zone” sort of atmosphere, everything in the room is the same.

When you stand on the original old floorboards and survey the bank counters and vault, you are seeing the same scene that Frank James and the other bandits saw as they came to the cashier window, drew their guns and commanded, “Throw up your hands. We are going to rob the bank. Don’t any of you holler. We’ve got 40 men outside.”

Welcome to Northfield, Minn. It is a peaceful little place today, an hour south of Minneapolis, that is proud of its slogan: “Cows, Colleges & Contentment.”

Although the town wants to be known for its beautiful and well-respected St. Olaf and Carleton colleges, Northfield can’t escape the notoriety of being the site of the last holdup of the James-Younger Gang. Today, it has an annual celebration in September, “The Defeat of Jesse James Day.”

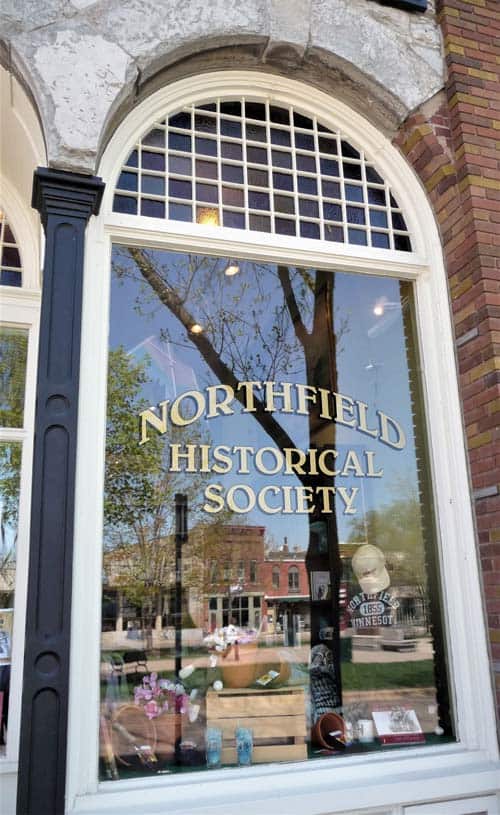

The Northfield Historical Society owns the Scriver Building where the robbery took place and they’ve done a splendid job of preserving the old bank with exhibits that detail the full seven bloody minutes that took place here on that sunny September afternoon in 1876.

There are saddles and guns that belonged to the outlaws, along with a rifle used by one of the town’s many heroes. You can almost smell the gunpowder and hear the gun blasts of the battle that took place just outside the front door.

The James-Younger Gang

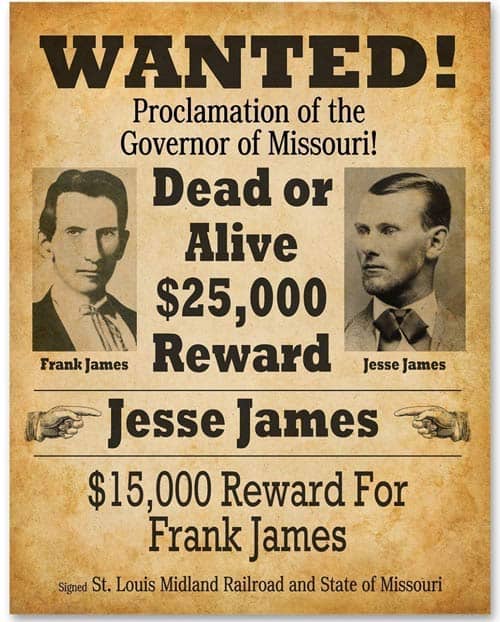

When the James-Younger Gang rode into town, the former Southern Civil War guerrillas were already well known as the most infamous desperadoes in America. Various members of the gang were credited with the nation’s first daylight peacetime bank robbery, one of the first train robberies, and some two dozen other daring holdups.

Frank James and Cole Younger had ridden with the vicious William Quantrill and his guerrillas during the Civil War, with both of them participating in the Lawrence Massacre, on Aug. 21, 1863, where almost 200 unarmed men and boys in Lawrence, Kan., were murdered and the entire town was put to the torch.

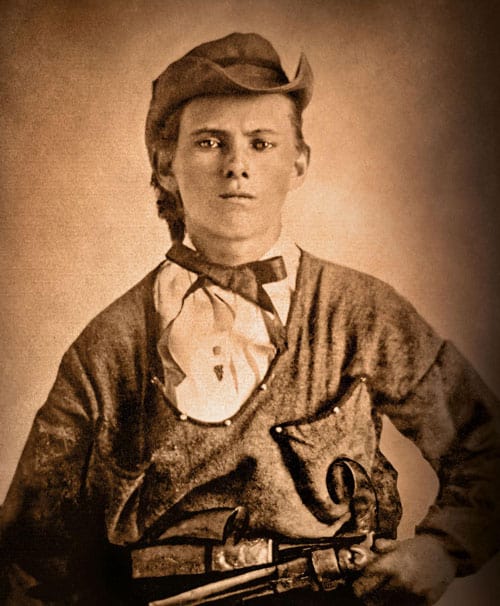

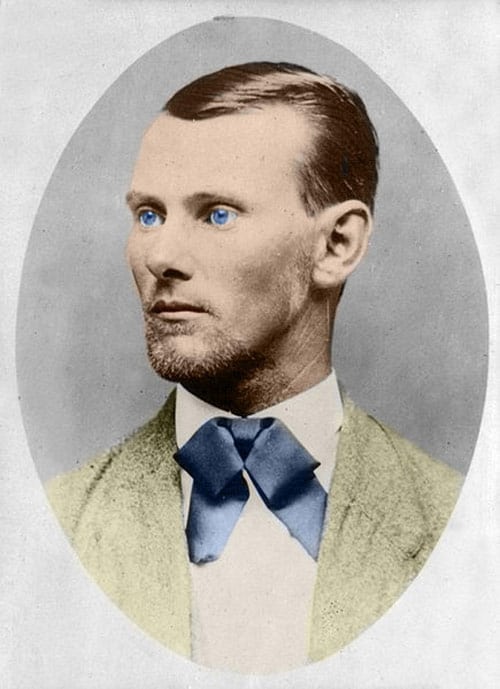

Jesse James became a Union-hating bushwhacker at age 16 fighting for Bloody Bill Anderson, along with his friend, 14-year-old Clell Miller.

Confederate bushwhacker leaders Anderson and Quantrill were both psychopaths and the guerrilla warfare they led in Missouri and Kentucky was the most horrendous of the Civil War, more like organized gang killings than military fighting.

When the war ended, many of the former bushwhackers naturally drifted into crime. Frank and Jesse James were especially well-known, lionized by Southerners as almost “Robin Hood”-like figures.

In truth, the bandits never shared their wealth with the poor and were involved in several cold-blooded killings of Pinkerton detectives assigned to capture them. But the James brothers could be kind to fellow Southerners they met during their crimes. In train robberies, they would often let Southern passengers keep their wallets and jewelry.

The sympathy for the James boys only increased when in 1875 Pinkerton detectives threw a bomb into their boyhood home, killing their half-brother Archie and gravely injuring their mother by blowing one of her hands off. Neither of the James brothers was in the house at the time, gaining them lots of empathy.

The Northfield Raid

By 1876, the outlaws were so famous in Missouri, it was too risky to pull jobs there, so they hit upon a plan to rob a bank in the rich farming country up north in Minnesota. Traveling in small groups to avoid suspicion, the outlaws told everyone they met that they were rich investors looking to buy farmland. That was somewhat true; to finance the bank job, the gang had robbed the Missouri Pacific Railroad of $15,000.

For a band of professional crooks, they made lots of mistakes. Hours before the robbery on Sept. 7, several of them got drunk. At 2 p.m., the town was uncharacteristically crowded with lots of people on the street, and worse, it was a small town.

When eight strangers all wearing long linen coats came into town together, the residents got suspicious. Especially hardware store owner J.S. Allen. He didn’t like the looks of the three men who went into the bank, so he strolled over and peeked in the window.

Outlaw Clell Miller was assigned to guard the street and be on the lookout for something just like this. Miller walked over, stuck a gun in Allen’s face and told him to move on and not say anything. With that, the entire holdup plan fell apart.

Allen bravely tore himself loose and ran down the street. With Miller firing shots at him, Allen yelled: “Get your guns boys. They’re robbing the bank!”

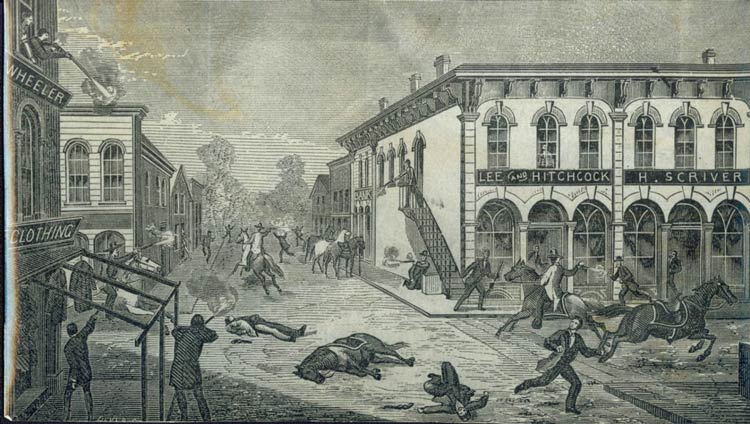

Other Northfield merchants took up the cry and the whole town started yelling. Miller jumped on his horse and along with Cole Younger starting firing pistols at citizens, telling them to get back inside. Jesse James and the other two bandits guarding the escape route became alarmed at the gunfire, and all three rode down the street, firing their guns, smashing windows, and telling everyone to go inside.

A Swedish immigrant, Nicolaus Gustavson, who may not have understood English, stood on the street watching the gunman. Incredibly, Northfield was scheduled to have a “Wild West” show that very afternoon, and he might have thought this was part of the show. At any rate, when he didn’t move, one of the outlaws shot him in the head, killing him.

It was hunting season for prairie chickens in Northfield, so lots of residents had shotguns loaded with birdshot. Elias Stacy grabbed his shotgun, walked out in the street and fired a load into outlaw Clell Miller’s face. The birdshot didn’t kill him, but it did knock the bandit off his horse and fill his face with blood.

Henry Wheeler was another Northfield spectator on the street watching the gunfire. A medical student from the University of Michigan who was on vacation visiting his family, he was a crack shot. He ran to a hotel across the street, got a rifle, went to a third-floor window and began shooting at the James Gang.

A.R. Manning, who owned the hardware store next door to the bank, grabbed his Winchester and a handful of cartridges and began his fuselage from behind a stairway. Soon, it seemed that everyone in town was firing some type of gun at the outlaws, who continued to ride up and down the street firing rounds at anything that moved.

Miller, the first outlaw to be wounded and covered with blood, got back on his horse just as Wheeler took a bead on him from the third-floor window and shot him through the chest, killing him instantly.

When Cole Younger jumped off his horse to see how Miller was, the hardware clerk Manning shot him in the left hip. Manning then shot Bill Stiles through the heart. Outlaw Charlie Pitts had dismounted and was using his horse as a shield, so Manning, the hardware store sharpshooter, shot and killed the horse.

Of course, the bandits noticed all these marksmanship and more than 30 shots were fired at Manning, splintering the stairs where he was hiding, but leaving him untouched.

With two men down and the whole town shooting, the outlaws on the street had to be wondering what was taking so long in the bank? Cole Younger remounted and rode his horse down the plankboard sidewalk to the bank window.

In the Bank

Nothing had gone right in the bank from the moment the three outlaws entered. With guns out, they ordered the three employees to lie on the floor; then the bandits rifled through the cash drawers.

There were only a few dollars and a bag of nickels; the drawer with $2,000 in it was lower, and the outlaws never noticed it. Inside the unlocked vault was $57,000 in cash but the vault door was closed. The bandits thought it was locked and never realized all they had to do was turn the handle.

Instead, they ordered bank teller Joseph Lee Heywood to open the vault. He said it was on a time lock and he couldn’t open it. The robbers beat him on the head, but he refused to talk. Another bank employee bolted for the back door and was winged in the shoulder, but escaped.

Outside, it must have sounded like a battle was being fought. Frustrated, the outlaws fired a gun next to Heywood’s ear, but he still refused to open the safe that was, of course, open all along. By now, Cole Younger was sitting on his horse outside on the sidewalk, yelling into the bank, “For God’s sake, come out, they are shooting us to pieces!”

The three outlaws in the bank gave up and walked out of the building and into a gun battle. One of them, probably Frank James, as he was leaving in total frustration, shot bank teller Heywood in the head, killing him. The desperate outlaws were so confused, they left behind the bag of nickels.

By now, the gang was taking severe carnage. All eight of them would be hit; two were killed, and they had lost a horse. Bob Younger on leaving the bank walked down the sidewalk and engaged in a one-on-one shootout with the marksman hardware store owner Manning.

They traded shots back and forth at close range when suddenly the outlaw took a shot to his right elbow. The medical student, Wheeler, had hit him from the third-floor window. Younger did a “border shift,” tossing the gun to his left hand and kept blazing away.

The only thought now was an escape. Charlie Pitts had no horse, but Cole Younger swooped him up, and the six remaining outlaws galloped out of town on five horses, Jesse James taking the last bullet in his thigh as they raced down the street in a cloud of dust for the last time.

The Hunt for the James-Younger Gang

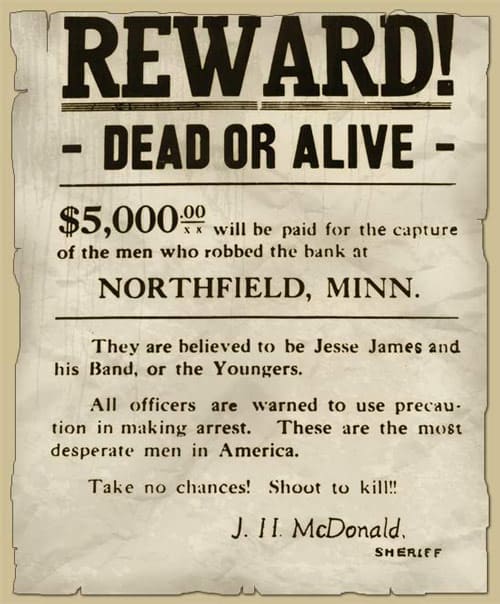

Among the many mistakes, the outlaw gang made was failing to cut the telegraph wires. They planned to do it after the robbery. Within hours, posses that would eventually reach a total of 1,000 men were on their tail.

Still, in 1876, the bandits held a lot of cards. They stole horses, hid by day and rode by night, and whenever they encountered someone, they told them they were part of a posse chasing the bank robbers.

For two weeks they eluded capture, trying to get back to Missouri. The James brothers figured they were the outlaws most wanted (and they selfishly knew they could move faster alone rather than traveling with the badly wounded Younger brothers), so they split off.

The James brothers not only made it back to Missouri, but they went back to robbing trains. Frank James was spooked by the Northfield disaster and later wrote, “I was tired of being an outlaw.” He decided to go straight. Years later, he surrendered and as part of a plea deal was found not guilty of all crimes and given a full pardon.

Jesse became increasingly erratic and dangerous, and his new gang of criminals was not on a par with the old. Finally, on April 3, 1882, one of his fellow outlaws, Bob Ford, decided to turn traitor and go for the reward on Jesse’s head. Waiting until Jesse was unarmed standing on a chair to hang a painting, Ford shot him in the back.

The Younger brothers and Charlie Pitts had a tougher time. After two weeks of running, the hungry, wet, tired and wounded outlaws were finally surrounded by a posse.

Charlie Pitts wanted to surrender, but Cole Younger said, “Charlie, this is where Cole Younger dies.” The posse opened fire and another bloody gun battle raged. Pitts took a bullet to the chest that killed him instantly.

Cole had eleven shots in his body before one bullet scraped his scalp and knocked him unconscious. Jim and Bob Younger were wounded again and surrendered.

The three brothers pleaded guilty, were given life sentences, and served as prisoners together at Stillwater Penitentiary in Minnesota. Bob died in prison; Jim and Cole were pardoned, but Jim could not adapt to being free and killed himself.

Incredibly, Cole Younger and Frank James got together later in life and started a Wild West Show that toured the country. Both of them wrote fanciful books that had little truth but gained them lots of notoriety.

In the end, it was Frank James who wrote the best epitaph of his life. “I have been hunted for twenty-one years. I have lived in the saddle. I have never known a day of perfect peace…We sometimes didn’t get enough to buy oats for our horses. Most banks had very little money in them.”

IF YOU GO:

Northfield is about an hour south of Minneapolis.

Go here for more information on the activities of the James-Younger Gang.

Author Bio: Rich Grant, a freelance travel writer in Denver, is a member of the Society of American Travel Writers and the North American Travel Journalists Association. He is the co-author, with Irene Rawlings, of “100 Things to Do in Denver Before You Die,” published by Reedy Press in 2016.

- Palawan Perfection: Exploring the Philippines’ Last Ecological Frontier - July 13, 2025

- A Journey to Ashland, Oregon’s Shakespeare Festival - July 13, 2025

- The Ultimate Guide to Cairo’s Top Three Museums: Which Should You Visit? - July 12, 2025