These days, the news is filled with stories about “the virus,” but it’s not the first virus that travelers have had to worry about. My first association with a deadly virus of a different kind began a year ago in April 2019 with a casual conversation at a cocktail party.

My brother Donald and I were due to fly to Rio in 11 days and I was telling an old co-worker that my itinerary included three days in Ilha Grande, a wild island off the coast of Brazil that other travel writers had described as one of the last great tropical island getaways.

Ilha Grande, Brazil

Ilha Grande had been a leper colony and then a maximum-security prison until 1994 and was now sort of a hippy tropical paradise with sand streets lined with bars, no motor vehicles, a small fleet of schooners that looked like pirate ships floating in the harbor, and daily sailing excursions to deserted beaches.

There was even more that made it sound like our kind of place: hiking trails through jungle to the prison ruins and waterfalls, and restaurants ringing a half-moon bay, where the waves gently lapped up to and just under your table, washing your ankles as you devoured a meal of fresh shrimp and caipirinhas, the oh-so-wonderful sugary cocktail of Brazil made with hard liquor sugarcane and lime.

By coincidence, my old co-worker had been to Ilha Grande and loved it. She said I would, too. And then she said casually, “Oh course, you got your yellow fever shot?”

Yellow Fever

I’d been sipping a fine IPA at the moment, and after it went down the wrong windpipe and I stopped coughing and choking, I said, “What yellow fever shot?”

She looked slightly embarrassed. “Oh. Well, maybe the yellow fever’s not there anymore.”

“What do mean by ‘anymore?’ Do you mean yellow fever has not been there since the 1800s, or since last year?”

She hesitated. “Well, it was two years ago. But didn’t they tell you that you need the yellow fever vaccine?”

“What do you mean by ‘they?’ I just booked a room. Nobody said anything about yellow fever. There’s nothing on the website!”

She looked dubious. “Well, maybe it will be OK. They may not still require the vaccine.”

You can bet that evening, even after several drinks, the first thing I did when I got home was Google “Brazil and Yellow Fever.” All the sites said, “not to worry!” Yes, there was an outbreak of yellow fever in Brazil, but it was confined to just one small remote island: Ilha Grande.

Yellow Fever Vaccine

A few more Google searches uncovered more bad news. There was a worldwide shortage of yellow fever vaccine. Yellow fever had killed millions throughout history and still kills up to 60,000 people a year, mostly in Africa.

Luckily, there was one travel medicine clinic in Denver that still had the vaccine. The catch: You had to have the vaccine 10 days before being exposed, and since I was leaving in 11 days, that meant I had to get the vaccine tomorrow.

I arrived at the office and filled out half a dozen medical forms. Then I was ushered in to get my shot or scratch or however the vaccine was going to be administered. The nurse was nice, and said casually, “Oh by the way, since you are over 70, I’m required to read this to you.”

She then read a document (filled with the usual horrors like the warnings you see on TV ads about taking any type of drug). But one thing stuck out. She said the incident of negative reactions to this vaccine for people over 70 was something like 10,000 times what it was for a younger person.

I said, “What does that mean?”

She said, “Well, at your age, one out of 30,00 people taking this vaccine is killed by it.”

“What!? Killed instantly!!? Here in this room?”

She laughed. “Oh no. You’ll linger for a few days.”

Well, I was thinking. Thirty thousand is a big number. What are the odds? Still. If you went to a Denver Broncos game at Mile High Stadium and, as you walked in, they said, “At least two people, maybe more, entering this stadium today will die.” Well, just saying, I might go in, but it would be hard to concentrate on the game.

But here it was: Yellow fever, a virus I thought had disappeared 100 years ago, was having an outbreak just where I was going, and to be safe, I had to take a vaccine that might just be more deadly than the virus itself.

I talked to my fiancee. She solved the problem. “Get the vaccine or don’t go,” she said. Well, that made it easy. I got the vaccine (administered by a scratch, by the way — you don’t even know it’s happened when it’s done). And that was that and I thought I am done thinking about viruses and will never again plan a trip where a vaccine is needed. Ha!

Rio de Janeiro

There may be a city in the world that is in a more spectacular setting than Rio de Janeiro, but I have not seen it. We found Rio to be classy, European, spotlessly clean and without a single challenge, except that hardly anyone speaks English.

Filled with pre-travel horror stories of crime and danger in Rio, my brother Donald and I had decided to be cool about what we did, and we made a vow that there would be no usual wandering aimlessly, drunk, on back streets at midnight.

We broke that rule on the first day. We walked everywhere in this magical city, in the day, on the beaches and late at night, all without a single incident. And most of the time on streets filled with single women just walking along without a care.

We rode the metro, buses, cabs, cable cars and aerial trams all without difficulty. The one thing we couldn’t do is ride the cog railroad to see Cristo Redentor – the famous Christ the Redeemer statue on top of Corcovado Mountain. The mountain is frequently covered with swirling clouds, and every time we went, that was the case.

At least they have a video remote of what the view is on top so you don’t waste money going up to be in a cloud. I’d been up enough mountains in clouds, fog, rain and snow.

How to Get to Ilha Grande

After all the recommendations from writers, I had assumed that everyone knew Ilha Grande and it would be easy to get there from Rio with tour operators offering package trips on every corner.

That turned out to be wrong. Almost no one we met spoke English and, if they did, they had never heard of Ilha Grande.

Without any other options, we were reduced to going to the main bus station. You meet an interesting sample of people at the bus station. Rich or poor, everyone in Rio at some point seems to ride a bus, which on long routes are beautiful, modern, clean and with restrooms.

But even in the bus station, the one ticket salesman who spoke a smattering of English told us our best shot was to take a bus to Conceicao de Jacarei, walk down to the beach, and there would probably be a small boat that maybe would ferry us over.

Conceicao de Jacarei

It seemed a bit sketchy, but it turned out to be fine. Conceicao de Jacarei was a sleepy village with nothing going on, but we bought a couple of beers at the bus stop, wandered down to the harbor, found a boat and hired a skipper.

And an hour or so later, we sailed into the harbor of Vila do Abraão, the only town on Ilha Grande. I’ve had few travel experiences that will ever match sailing into this village for the first time.

Like Pirates of the Caribbean

It was “Pirates of the Caribbean” come to life. Exactly as billed, it was an unspoiled village of one- and two-story buildings right on the beach and spreading up into the jungle. There were only a few streets, all made of sand, but they were filled with cafes and bars.

Since there is not a single car on the island, it was so quiet you could hear the birds and surf, listen to the swaying of palm trees overhead, smell the pot that hippies were smoking and hear the caps being popped off beers at the bars.

All the activity of the town focused on the dock, where boats would come and go constantly, bringing shipments of beer and food, and unloading quickly to let the next boat come in. The town loafers would sit there all day and just watch the boats come and go.

Salespeople for the schooner fleet, all young and attractive, would sometimes wander over to sell their tours to people arriving by small boats, but mostly they just sat in their little thatch-roof shops along the bay, waiting for customers to come to them.

There was no need to advertise because, from any place in town, you could see the gorgeous fleet of two-mast schooners floating in the harbor, a scene from the 18th century with palm-tree covered mountains as a backdrop.

It took us maybe two hours of exploring to find the best view bar in town, where at happy hour you could get four caipirinha cocktails for $5 U.S. total and watch the lights of the houses and bars and small inns come on one-by-one along the half-moon ring of the harbor beach, as the music of isolated guitar players and drums drifted up from the village.

If it is not already ruined, Ilha Grande will be. Perhaps the yellow fever outbreak and COVID will slow down the creep of tourism and development. Before COVID-19, hardly anyone even thought about a virus or disease. More of a concern in Ilha Grande, we learned, was that 19 people in the town had been killed in 2010 by a mudslide.

My brother and I, loaded up with yellow fever vaccine (he had previously gotten the vaccine working in Africa) figured we were invincible. We walked fearlessly through jungle trails to what must have been hell-on-earth prisons and leaped across streams and waterfalls.

We did cover up with insect repellant, but more against bites than yellow fever. We sailed on pirate ships and jumped off to swim ashore to islands and beaches that had no electricity or residents. We drank endless amounts of beer (Brazil has the coldest beer in the world, usually severed from tubs of floating ice) and caipirinhas cocktails, and dined on fresh shrimp. Nothing went wrong.

Would we do it again today in a COVID-19 world?

No, I don’t think so.

Travel in Brazil Today

It was just a year ago, but yellow fever was something out of the 18th century. Carried by mosquitoes, the virus actually dates back 1,000 years.

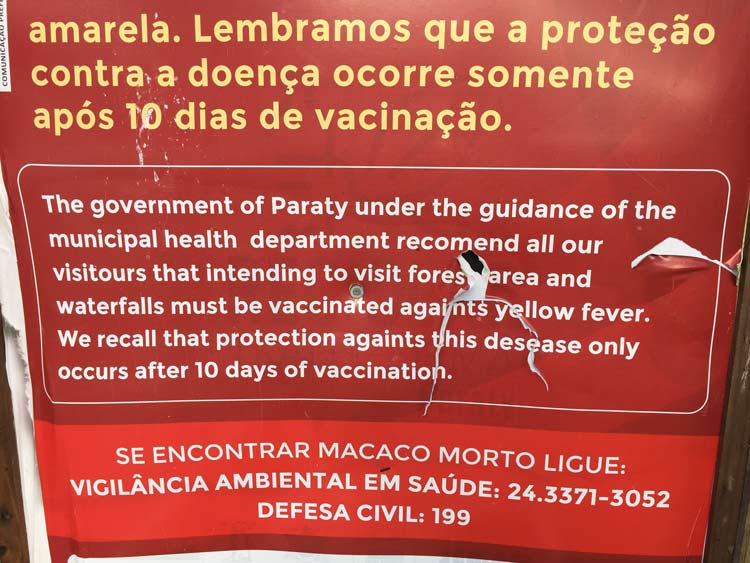

We know a lot more about viruses today than we did last year. My brother and I saw plenty of signs saying don’t go here if you have not had a yellow fever vaccine. We took selfies in front of them and had a laugh. We had the vaccine!

Will it be the same with COVID-19 after the vaccine? For young people, I hope so.

It’s going to take some courage and a realistic look at numbers and risk level, but once there is a vaccine (and maybe even before), I think the urge to travel is just too strong, and with time, COVID-19 will be no more of a distraction to young travelers than yellow fever was to us.

But to other, older, more risk-conscious travelers? Who can say? One thing I am certain of — if you’re going to Ilha Grande, get the yellow fever vaccine.

PARATY – ILHA GRANDE’S GRAND BROTHER

When Ilha Grande was a prison colony, Paraty was the rich colonial town nearby on the mainland that was the prison’s lifeline to the world. Paraty is not undiscovered. It is a UNESCO World Heritage site and is about equal distance from Rio and Sao Paulo, which means that about half of Brazil heads there on the weekend. And with good reason. It is simply marvelous.

The Old Town is a huge 40-square-block area closed off to vehicles and stuffed with stone churches, cobblestone streets, horse-drawn carriages, and a harbor full of schooners and brightly painted boats (10 times as many boats as on Ilha Grande). It looks just like it must have looked 100 years ago. Except that the old stone buildings now house wonderful shops with windows full of art and fashions, galleries of Brazilian handicrafts, and restaurants that spill out onto the cobblestone streets with bustling waiters and brightly colored tablecloths. Old-fashioned lanterns give the town a wonderful glow at twilight.

A unique feature of Paraty is that at certain times of the year, high tide comes in and washes the streets, turning the village into a small Venice. We happened to be there at this time.

All the streets were covered with water — water too deep and too dirty to venture into. The shops threw up little wood plank bridges to help people get around, but many streets became inaccessible.

As the tide went out, the water retreated, tables and outdoor cafes came back out, and it was as if the flood and cleansing had never happened.

With the nearby mountains, jungle, pounding surf and cobblestone streets, Paraty has the feeling and look of Old Puerto Vallarta, but a Puerto Vallarta from the 1970s.

There are very few American tourists, and it is still, above all, a real town. We witnessed a religious parade with hundreds of townspeople in robes marching with candles and singing songs as they walked from church to church. Paraty is only about a three-hour bus ride from Rio De Janeiro, and a must-see if you are that close.

BUZIOS — THE TOWN MADE BY BRIGITTE BARDOT

The really chic, upscale beach resort near Rio is Buzios, a town made famous after Brigitte Bardot stayed here in the 1960s.

Brigitte compared it to the early French Riviera, and that’s a good comparison. Her love for the town brought international publicity. In thanks, Brigitte is honored with a statue near the center of the resort village, and grabbing a selfie with her statue is almost required.

There’s a definite European vibe to the area, which is home to 20 beaches and a trendy village pedestrian center of cobblestone streets, outdoor bars, beachside restaurants, elegant windows packed with trendy fashions, live bands, and great late-evening people watching.

It’s a bit slow in the day as people are out diving, snorkeling, beach relaxing, sailing or hiking, but come twilight, the town becomes as romantic as any beach resort in France or Spain, and a bit more exotic.

With 20 beaches, Buzios spreads out over quite an area. It’s not all beautiful. Some of the outer towns are tacky for people just looking for a beach. For romantic Buzios, pick a posada within walking distance of the Brigitte Bardot statue (the most prominent local landmark) and you’ll be in the center of everything.

There is a direct bus service of two to three hours depending on traffic to Rio’s International Airport, so Buzios makes a great place to unwind after a trip to Brazil and you can leave directly from the beach to the airport.

Just be sure it’s the right airport. I didn’t look closely at my ticket and only realized after arriving at the international airport that my international flight back to the states left from Sao Paulo.

First, I had to take a domestic flight to Sao Paulo from a different airport 10 miles away. No worries. Cabs in Rio are cheap if a bit nerve-wracking due to the driving habits and incredible speeds. It’s a rare car you see in Rio that doesn’t have some type of dent or scratch on it. But that’s why they invented caipirinhas! And you’ll never find a colder beer than in Brazil. There are no laws against open containers and you can drink wherever you like. Which comes in handy on a taxi ride.

IF YOU GO:

Of course, all unnecessary travel to Brazil is currently banned due to COVID-19 and will probably remain difficult until there is a vaccine. The President of Brazil has caught COVID – twice! You will also need a yellow fever vaccine if traveling to Ilha Grande or Paraty. Information.

Author Bio: Rich Grant, a freelance travel writer in Denver, is a member of the Society of American Travel Writers and the North American Travel Journalists Association. He is the co-author, with Irene Rawlings, of “100 Things to Do in Denver Before You Die,” published by Reedy Press in 2016.