The Ideal Vacation

Gazing through the porthole of a large ocean-going vessel is the ideal vacation for some. If that porthole is 200 ft. below sea level and you gain access to the cabin via a hole blown in the side of the ship by a torpedo.

You’re wearing a twin rig of scuba tanks holding what would seem to be not enough air to fill a refrigerator, well, you’re looking at a rather different experience.

For those who enjoy diving and can endure the somewhat lengthy trek to its remote shores, Chuuk, formerly Truk, contained within the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), offers a checkered history and unparalleled scuba experiences.

Diving in Micronesia

Chuuk – rhymes with duke – is not easy to get to, yet streams of scuba divers fly there week in, week out to take advantage of what is described, with good reason, as the greatest wreck-dive experience in the world.

It’s been the Holy Grail for underwater adventurers since 1969, when famed explorer Jacques Cousteau made a documentary on the maritime graveyard.

This is not an adventure for the faint of heart. Technical diving (using different blends of gases to allow more time underwater) is, to a large extent, the pursuit of those with strong muscles.

The sheer physical strength needed to maneuver the equipment into the water is a challenge in itself.

The contrasts experienced by travelers to tropical islands are all present here; volcanic peaks (Chuuk means “mountain” in the local language) covered in almost-painful emerald hues etched against a perfect blue sky.

Palm trees and white sand beaches bordering calm turquoise and sapphire lagoon waters that reach temperatures higher than the resort showers.

Chuuk

In Chuuk, the most populous atoll of FSM, apples and blackberries are still something you eat, internet access is very much a hit-and-miss affair, mobile phone coverage is virtually non-existent.

When they run out of eggs or coffee, you may have to wait a week or more for the supply ship to arrive. If you’re after a five-star resort experience, this is probably not the ideal destination.

As with most tropical island destinations, one must be prepared to adopt a different concept of time.

Nobody hurries here; things happen when they happen and visitors are bound to be a lot more content if they can come to terms with that before arrival.

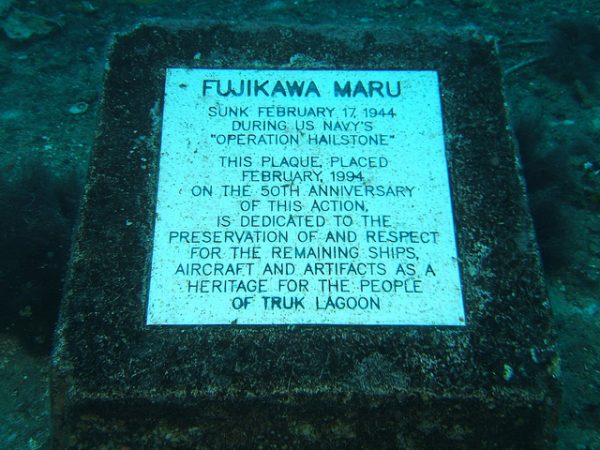

The poor and the rich jostle side by side as the airport transfers ferry gadget- and cash-laden tourists through areas of great poverty, skirting the bones of buildings devastated by US bombs dropped during Operation Hailstone (sometimes mistakenly called Hailstorm) in February, 1944 and others destroyed by mudslides after cyclones.

Chuuk has endured a complex history, having been colonised and controlled by various nations since the 16th century. The Spaniards were early visitors who claimed the Caroline Islands (as the group was then named).

Spain later sold the group to Germany, who lost it to the Japanese Empire following a mandate by the League of Nations after World War I.

The Location

The location of the island group sealed its fate during WWII; it was perfectly positioned to serve as the Empire of Japan’s heavily fortified main base of operations in the South Pacific theatre.

Chuuk, with its calm protected lagoon, became the temporary home of a great portion of the Japanese fleet.

When the US discovered its location they unleashed a massive retaliation for Pearl Harbor.

Over three days that sent many of the requisitioned Japanese merchant navy ships to the bottom, along with their crews and cargo.

The previously pristine shallow tranquil waters of the lagoon were littered with wreckage and bodies.

Many of the ships sank in an upright position and all the wrecks have, in the past 70 years, been covered with spectacular hard and soft coral growths, sponges, seaweeds and other marine life.

Although they are still clearly recognizable as marine vessels. Brilliant tropical fish swarm around gas masks, bedpans, canvas shoes, sake flasks and live ammunition clearly visible on the decks and in the holds of the sunken fleet.

Wreck Diving in Chuuk

Many of the wrecks are classified as “penetrable” – they are open enough for sport divers with no wreck-diving experience to explore holds and passageways.

Tech divers with more training under their weight belts can enter an eerie world where time stands still.

Bathrooms with not a crack in their white porcelain tiles and urinals; galleys with pots and other cooking equipment littering the floor; army vehicles, planes in holds.

And companionways and narrow staircases festooned with lush growths of seaweed and soft coral lie in wait for divers who have the necessary training and equipment.

The San Francisco Maru sits upright on the sandy bottom at 200 ft. The depth allowed me a maximum of 20 minutes to explore the holds in which most of the relics lie.

It followed by a lengthy ascent to allow for the necessary decompression stops.

Logistically it’s not an easy dive; divers carry twin tanks on their backs and a “pony” bottle (a smaller capacity tank) filled with a mixture of nitrogen and oxygen – Nitrox – slung under the left arm.

Some choose to also carry unwieldy camera rigs with powerful lighting equipment.

My First Time Diving

All the gear takes a heavy toll on the back; the first time I donned the rig I remember thinking there was a distinct possibility that the weight would cause me to sink.

It might be an uncontrolled descent to the ocean floor like a very large and not terribly graceful stone.

Penetrating the wreck while festooned with all that stuff thus becomes an exercise in calculating if the sheer bulk of the equipment will allow you to fit through doorways and companionways without snagging.

For someone who has suffered claustrophobia her whole life, it was a personal challenge that took some soul searching before tumbling backwards over the side of the dive vessel.

Apart from the obvious dangers, a tech diver must be completely confident that they will be able to control any panic they might experience; anything less can, and will, place any dive companions at risk.

And there’s no quick escape from that depth.

The dangers are well worth it – the San Francisco Maru carried three Type-95 light tanks (each weighing 7.5 tons), Jeeps, fire engines, torpedoes, sea mines and shells, all largely intact and easily recognizable.

Aerial photographs of Operation Hailstorm showed the ship’s stern on fire after attacks by dive-bombers; it is in remarkably good condition for all that.

The Fujikawa Maru (at 111ft) contains Zero aircraft in one hold, transported with their wings removed (they can be seen in the adjoining hold); the instrument panels, joysticks and pilot seats are clearly evident in the slim tubes of the undamaged fuselages.

The deck of the Hoki Maru lies at 150 ft; she contains Caterpillar tractors, a steamroller and other large construction machinery.

Inevitably, there are also human remains; all the wrecks are designated as war graves and tourists are asked to not remove anything while diving.

Finding A Skull Under the Water

There is a skull clearly visible in one of the shallower wrecks designated safe for sport divers; it has been placed on a shelf by the local dive guides to provide a frisson for the less-experienced adventurer.

The wreck of the Shinkoku Maru has a well-preserved operating theatre deep in its bowels (the only one in Chuuk, as it turns out); the former oil tanker.

It participated in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor sank so quickly that surgical instruments and other equipment is still on the operating table, along with a rather theatrical pile of human femurs.

The temptation to souvenir one of the countless artifacts is strong, but the penalties if caught are severe, with good reason.

During my stay divers from several nations complained bitterly about the rules; more than a few boasted of the items they’d pilfered from wrecks where no rules applied.

One said he and his friends regularly dived with a pinch bar to remove portholes and other fittings, which he’d had built into his home as architectural features.

He admitted (with not a trace of embarrassment) that those particular wrecks were no longer worth diving on as there was nothing left to see.

Bags are frequently searched when divers are departing Chuuk for home; hopefully their strict regulations will ensure that the experience will be available to others for a few more years at least.

The ocean, however, is not a kind environment for man-made objects; some of our party who dived the site several years ago noticed a marked deterioration of the wrecks and a serious reduction in fish life.

There will come a time in the near future when the area is no longer safe for penetrating dives.

The depth of the technical dives demands a slow and steady ascent, with a swap to the Nitrox pony bottle at a depth preordained by a set of tables that must be strictly adhered to.

Deep dives are carefully planned before they are embarked upon, with “bottom time” (duration of the time spent on the wreck) and times and depths of stops written on an underwater slate carried by each diver.

Stops are made hanging onto a shot line, a rope dropped from the dive boat that is attached to the wreck.

Divers must remain as horizontal as possible during the lengthy wait, as that position aids in the elimination of excess nitrogen from the body.

If anyone ever invents a waterproof digital reading device, I predict the main users will be tech divers.

Forty minutes spent gazing at an invisible ocean floor seems like an eternity.

All divers have an enforced period on dry land for a set time before they can be on an aircraft.

Otherwise the change in atmosphere can bring on a case of decompression sickness (otherwise known as the bends). So it’s as well that there are activities to keep them amused for the last day of the trip.

For the duration of my stay on Weno, the prospect of developing the dreaded condition – brought on by gases dissolved in the bloodstream while diving converting back to gas (causing bubbles in the body).

It caused me to be especially diligent in following the rules.

The most common treatment for the potentially fatal condition is hyperbaric oxygen therapy delivered inside a recompression chamber.

All well and good but the one outside the dive shop from which we departed daily was a torpedo-shaped iron device covered with surface rust about the size of a large coffin, with the lid secured by huge bolts.

Safe end-of-trip activities include snorkeling off the resort where I stayed on the main island of Weno.

The coral is good and there are several wrecks in very shallow water, visible from the shore, that are accessible without scuba gear.

Kayaking, windsurfing, fishing trips and other water activities are available, and there are sightseeing mini-buses that allow tours of the bomb-damaged former Japanese communications headquarters (now the Jesuit-run Xavier High School).

A huge cannon-like gun bolted to the floor of a mountainside cave hewn by hand, using crowbars, by the Chuukese under the “guidance” of Japanese military personnel.

Day trips are also available to other islands and atolls in the group; visitors can explore the ruin of the original WWII airstrip and snorkel around the wrecks of two aircraft in shallow water.

Tourism is the chief source of income for the locals; the poverty is sobering and many live a subsistence lifestyle. Roads are in an appalling state of repair.

The trip from the airport in Weno to the resort took us 45 minutes to travel less than six miles – and the Chuuk custom appears to be to abandon cars if they break down; the roadsides are littered with derelict vehicles.

The Chuukese are mostly friendly but tourists are advised to not venture outside the resort compounds at night. The contrast within the resort area to the lifestyles of the indigenous population is marked.

Most of the houses are crumbling concrete with rusting iron roofs, many with enormous holes, and a typical family home has headstones in the yard marking the resting place of loved ones.

The influence of the missionary school is evident in the spotless uniforms of schoolchildren.

Access to Chuuk is via Guam; the flight ends on a hair-raisingly short runway – a meager 1640ft. The jolt from the rapid deceleration is rather stimulating,and that’s just the start of the adventure.

Good thing I packed extra adrenaline.

Biography: Maggie Cooper is a freelance food, travel and pop-culture writer whose columns appear weekly in an Australian newspaper. She lives in several locations surrounded by the spectacular natural beauty of Tasmania, Australia’s island state.

- Top 10 Things to Do in Ireland - April 25, 2024

- How to Get Around in Sydney: A Local’s Guide to Traveling Around Sydney - April 24, 2024

- The Low-Key Magic of Ghent, Belgium - April 22, 2024