October is grape harvest time in Spain. While tourists never really crowd the Basque part of the Rioja wine-growing region, they start thinning out at summer’s end. That’s hard to figure, since it’s an area where wine is hardly the only thing to drink in. Besides inventive restaurants and graceful medieval views, the Basques have a proud history, and most residents seem to have an easy-going, self-effacing air.

If I had a dollar for every time I heard one particular regional joke/proverb during our week’s trip, I’d have enough for a nice meal. It goes: “Sex is not a sin here, it’s a miracle.” The point seems to be that the always-industrious Basques now are busily re-shaping their rust-belt image into one of high-tech and haute cuisine.

The Guggenheim museum, designed by Frank Gehry, which opened in 1997, spawned a term called the “Bilbao Effect,” which notes that impressive architecture can attract worldwide attention and bring in tourists.

Local wineries are working to attract new visitors with their own dramatic buildings, so the present peace and quiet might not last. Outside the walled, hilltop village of Laguardia (which our Lonely Planet guide called the prettiest of the wine towns) is the Marqués de Riscal Winery. French Winemaker the Marqués de Riscal brought French Médoc viticulture to this winery in the 1850s, though local winemaking pre-dated that by centuries.

Rioja wines lean heavily on the distinctive tempranillo grape, but during a tasting at Marqués de Riscal Winery, my favorite was the 1998 Gran Reserva cabernet. Owing to the vintner’s century-and-a-half relationship with France, Riscal has special dispensation to use cabernet grapes.

A high point of the Riscal tour included a walk through the ancient cellars, where cobwebs partially hid bottles of every vintage since 1862.

Riscal’s ancestors recently built a Frank Gehry – designed winery, hotel and spa. The five-star Hotel Marqués De Riscal opened last month; it has 43 luxury guestrooms and suites, a restaurant and spa. The building is draped in undulating metallic fabrics like a Michelangelo Madonna.

Close to the Marqués de Riscal Winery, the magnificent Ysios Winery was built by another hot architect, Spaniard Santiago Calatrava, in 2001. From afar, Calatrava’s undulating wine cathedral appears pixilated as it rises dramatically from the stony vineyards. In contrast, tucked away among Ysios grape vines is a dolmen, a sort of stone igloo built around 3000 B.C. by Druid-like ancients, which highlights the modernity of Calatrava’s shrine to wine.

Calatrava also designed a signature footbridge in downtown Bilbao. In the United States, Calatrava was responsible for the soaring 2001 redesign of the Milwaukee Museum of Art. He is now upping the ante with his proposed world’s tallest building in Chicago.

In contrast to the modernity of the two wineries, the town of Laguardia, Spain is full of medieval ambiance. Kids play soccer on the cobblestones in front of the Gothic Church of Santa María de los Reyes, which, thanks to a sheltered portico, has about the best-preserved Gothic art anywhere. Life-sized and vividly painted 14th century figures, including Mary, Jesus and the apostles, look down on modernday visitors.

After an unforgettable meal of hake chins in the regionally distinctive pil-pil style (sautéed with garlic and olive oil) in our hotel, Hotel Villa Laguardia, we headed a few miles north to coastal San Sebastián feeling like Hemingway’s protagonist in The Sun Also Rises. (Jake Barnes went to San Sebastián to swim off the debaucheries of wine-soaked Pamplona.)

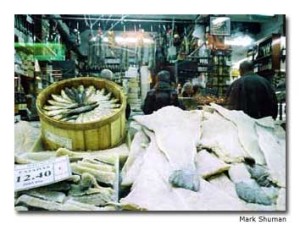

San Sebastián, little sister to France’s Biarritz, was a playground for the rich before and during the Jazz Age. Here, tapas are called pintxos(pronounced “pinchos”).

This food art in miniature is made from an array of seafood, mushrooms, beans and peppers. The New Basque Cuisine Movement of the 1980s means you can now find both old-school and adventurous pintxos, depending on the venue.

One tapas bar offered purple sea urchin shells stuffed with fresh shrimp salad. The chef scattered the tiny urchin bowls and sauteed scallops in their shells over a plate of Parmesan cheese “sand” for an edible seascape.

Obviously, food is a local passion here. San Sebastián’s old town, timeless and busy, in the traditional Spanish way, is crowded with cafes. Gastronomic pub crawls, called poteo in Basque, are a vital part of an ordinary day. Residents try to hit as many spots as possible before heading home after work. Private, do-it-yourself dining societies are another tradition, and for a town of about 180,000, San Sebastián boasts an amazing total of 14 Michelin- starred restaurants.

To recover from the excesses of food here, walking helps, and there are incredible views from atop Monte Urgull, which you can reach by following the path up from the Plaza de Zuloaga. Queen Maria Cristina’s Miramar summer palace can be seen from Urgull.

In Bilbao, Spain, almost directly west of San Sebastián you can still spot old-timers wearing traditional bright-blue berets, a nationalistic touch that recalls a Basque history that may go back 25,000 years. Neither French nor Spanish, the Basques were granted autonomy in the Middle Ages and lost it only in 1876. As they are ethnically, linguistically and culturally distinct from the rest of Spain, the local pride is understandable.

Of course, you can’t miss the Guggenheim in the middle of a river walk that bisects Bilbao. Chicago architecture critic Ed Keegan said he feared an “emperor’s new clothes” reaction to the museum when he visited, but he was wowed.

The Guggenheim is a titanium-skinned museum built to look like a boat with a fantastic lofty interior, atrium and enormous outdoor sculptures. Known for traveling exhibits, the Guggenheim also has a collection of works by Kandinsky, Miro, Picasso, Rothko and other masters.

Guernica, a Spanish town where leaders of the Basque people traditionally gathered each year under an oak tree, was mercilessly bombed in 1937 during the Spanish War. The local church was spared, but the rest of the town and the civilian population were ravaged, becoming a worldwide symbol of the horrors of war.

Today the town is necessarily modern. Yet, in addition to the church that still stands, another important symbol remains: Remnants of the oak tree that’s symbolized Basque identity for centuries.

If You Go

Marqués de Riscal

Vintage Spain offers winery tours.

Spain Tourism

- Travel Guide to Colorado - April 26, 2024

- Travel Guide to Croatia - April 26, 2024

- Top 10 Things to Do in Ireland - April 25, 2024