We are reader-supported and may earn a commission on purchases made through links in this article.

I am flying to Funchal, Madeira, from Porto at the ungodly hour of 5:50 a.m., the sort of timing that saps the will of even the most intrepid traveler. No one thinks of doing anything worthwhile at that hour other than going back to sleep as quickly as possible.

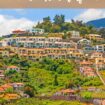

Air service is limited here because Madeira is isolated. The result: Being a wee speck of volcanic rock in the Atlantic Ocean, closer to Morocco than to your parent country, Portugal, can sometimes be…inconvenient.

But oh, the benefits of traveling in Madeira! Think food—garlic-rubbed barbecued beef, fresh as ocean-spray seafood, savory cakes. Think poncha, the island’s fruity go-to beverage made from pure-cane rum that will knock you on your fanny before you even realize you’re tipsy. And more than anything, think wine (lots and lots of wine).

Madeira is more than comestibles, of course; it has a culture all its own—which, happily enough, usually includes lots of food, poncha, and wine.

I am traveling with a small group on a trip organized by Sagres Vacations, which specializes in deep-dive tours of Spain and Portugal, including the Azores and Madeira. Fortunately for me, the half-dozen other travelers are every bit as hungry and thirsty and curious as I am. Another plus: Sagres always builds in plenty of free time for its guests to go exploring on their own.

A Drippy, Garlicky Pork Sandwich to Remember

At the first chance I have, I split from the group and head to Funchal’s farmers market, Mercado Dos Lavradores. I’ve been eager to try an iconic local dish called carne vinha d’alhos, two-inch pork-shoulder chunks marinated in white wine, garlic, vinegar, pepper flakes, and bay leaves in a clay pot for up to three days, then cooked in a skillet with the marinade. Caci Café, near the front entrance of the market, specializes in it, served as a sandwich, so I figure I’ll give it a try.

The café itself is not going to win any awards from Architectural Digest; it is plain to the point of having no design at all, just an order counter and three tables inside. A dozen more tables fill the sidewalk out front. But I’m not here for elegance; I’m just plain hungry.

The sandwich is a drippy, garlicky pork stew on a roll. I don’t just eat it; I wallow in its juiciness, the rich pork flavor, and the soft but chewy Madeiran bread called bolo do caco, made from wheat flour and sweet potato. Next time I’ll eat it the way the locals do, with a couple of napkins wrapped around the bottom to catch the juices before they roll into the palms of my hands and down my arms.

Caci is a simple place with limited waiter service. I can’t vouch for the other dishes, but I will long remember the vinha d’alhos. With a large glass of Coral beer, my meal totals about $7.50 U.S.

You will not go broke eating and drinking in Madeira.

Read More: Enigmatic ‘Ilha’: Mozambique’s Spectacular Colonial-Era Ghost Capitals

The Octopus Question

Anyone who is half-serious about food on this curious island inevitably arrives at the cephalopod dilemma. Seafood abounds here, and the fishermen catch lots of octopi. We can all agree that eating an octopus is on the nasty side of culinary considerations. They have toothed tongues, for crying out loud. On the IQ spectrum, they’re smarter than dogs and just behind dolphins—and no one likes to eat an intelligent animal. Oh, I have chowed down on octopus before, in ceviche, but at least it was cooked. At Lapa Bay restaurant in the charming coastal town of Porto Moniz, I go all in and order it raw, carpaccio de polvo, with marinated tomatoes and olive tapenade. I think there may even be a bit of octopus ink in that tapenade.

And it is superb. Not chewy the way, say, calamari often is, but tender despite being uncooked, with the tang of the sea, pleasantly enhanced by the tartness of the tomatoes and the richness of the olive paste. Just don’t look too closely and you’ll be fine.

The taste, I’ll admit, is possibly improved by the setting. The north coast of Madeira, where we dine, is fringed with verdant mountainous cliffs, pocked here and there by leaden basalt lagoons, and flecked with the occasional black-sand beach carved by the waves at the base of the plentiful oceanfront escarpments. Parts of the north shore look like Tahiti, the rest looks like the Nā Pali coast of Kauai. One could hardly ask for a more sumptuous view while chewing long, paper-thin, nearly translucent slices of octopus tentacle.

Marbled Beef on a Long Wooden Skewer

A highlight among my many memorable Madeiran meals is lunch at Quinta do Furão, a vineyard and hotel on a bluff overlooking the sea on the north coast near Santana. It isn’t just the restaurant’s interior that enchants me (though I do fall in love with the rustic wood-and-stone design, the open fireplaces, and the views of mountains and ocean through the wide windows), but the menu as well.

Book your stay at Quinta do Furão here

Best Tips & Tools to Plan Your Trip

Here, at last, I am able to try the much-loved local dish called espetada. Made from large cubes of tender, marbled beef tenderloin, the meat is skewered on thin laurel branches, rubbed with a mixture of coarse salt and garlic, then grilled with whole bay leaves over an open flame until the juices flow. Mine is served on a plate with fresh tomatoes, julienned carrots, chestnut-flavored Madeira beans, and milho frito, similar to polenta, cubed and fried. On the side is a bowl of tomato soup topped by a poached egg.

“It smells amazing,” says Patty, one of my fellow diners, as she stares ravenously, enviously, at my plate.

And it tastes even better.

There is no end to the intriguing, toothsome regional dishes I sample during my trip, but I am disillusioned on the one occasion I try a celebrated Madeiran sandwich called prego no bolo do caco—basically, extra-thin slices of grilled flank steak, flavored with salt, garlic and bay leaves, and embellished with cheese, tomatoes, and lettuce.

I find an outdoor café that serves the dish during one of my ad-lib evenings. What a disappointment. The meat reminds me of frozen Steak-umms—chewy and tasteless. Not many Madeiran dishes underwhelm me, but this one does. At least the bread is good.

Read More: Off-the-Beaten-Path Excursion to the San Blas Islands in Panama

Be Careful, Very Careful, When You Drink Poncha

I head over to Toka de Baco, a hole-in-the-wall in Funchal’s tiny but super-lively Old Town, to drown my culinary sorrows in a glass of poncha. Or perhaps several. The typically Madeiran drink is based on locally made rum from pure cane sugar. To the alcohol, the mixologist adds honey and fruit juice (lemon is the most traditional; passionfruit is among the most popular), then mixes it with a long-handled muddler called a mexelote by some but a caralhino (“little penis”) by many.

The flavorful beverage comes across more like a citrus punch than a powerful cocktail. It has little if any alcohol taste because of the sweet honey and strong fruit flavor. That’s why imbibers should be leery: Four or five ponchas may go down easy, but as you prepare to leave the bar, you realize that your legs no longer work and you don’t remember where your hotel is.

View other hotel options in Madeira here

Although poncha is a local favorite, Madeira is best known for its wine, especially the wine to which the island gives its name. Madeira wine can be produced from more than 30 different grape varieties, but Sercial, Verdelho, Bual, and Malvasia are the so-called “noble four.”

What makes Madeira wine unique is that it is oxidized through heat and aging and “fortified” by distilled spirits. Madeira can be either sweet or dry, and has an alcohol content of 18-21 percent, unlike still wine, which averages 12-14 percent alcohol.

Wine Tasting in the Madeira Mountains

Still, wine accounts for only 5 percent of the island’s total output, but local winemakers are becoming more confident in their ability to make high-quality nonfortified wines. The most popular white grape is Verdelho, dry and bright, while the most favored reds are Touriga Nacional and Tinta Roriz (called Tempranillo in Spain). There is almost no export of the limited production of still wines, so many visitors make a point of buying several bottles to pack in their suitcases for home consumption later.

Our crew sets off to sample some of those wines on a sunny afternoon high in the island’s central massif. We are en route to one of Madeira’s justifiably well-regarded wineries, Quinta do Barbusano, whose steeply terraced mountain vineyard overlooks the sea on the north shore—and whose tortuous rutted road is an adventure in itself.

“Madeira is a volcanic island, so our wines are more acidic and very dry,” says our wine guide, Juliet, who works for the winery. “Our biggest problem is the weather. It’s very humid, which can cause a rot on the grapes.”

The sloping terrain, the different weather conditions on the wet north shore compared to the sunnier, drier south, and the proximity to or distance from the ocean all add to the complexities of growing grapes in Madeira’s many micro-climates. To emphasize the point, on our stroll through the Barbusano vineyard, Juliet points to the vines farthest from us.

“The grapes at the northern end of our vineyard are saltier than the rest because they’re closer to the sea,” she says.

Quinta do Barbusano produces 80,000-100,000 bottles a year. “And we drink it all here at the quinta,” says Juliet with a laugh.

The Grape Harvest Festival—the Liveliest Madeira Tradition of All

Although producing still wines might be breaking from custom on the island, there is one tradition that has gone unchanged for centuries: the annual wine harvest festival.

Here’s the way I remember it—and because of all the wine and poncha poured that day, I may be charitably described as an unreliable narrator.

There I was, in a taberna the size of a broom closet, drinking poncha at 9:30 on a cool September morning. Don’t judge: Island time can do that to you—especially during the annual Wine Harvest Festival in Estreito de Câmara de Lobos, a comely grape-growing settlement on the south coast just west of the capital, Funchal.

Visitors are encouraged to walk up the steep main street to the top of the hill and cut grapes off the vines in the communal vineyard. Someone hands you a pair of clippers (you can’t realistically pluck bunches of grapes with your fingers; you’re likely either to hurt yourself, crush the grapes, or both) and you put the grapes in a basket. When you return with a full basket, the overseers instantly hand you an empty one. It’s up to you when to say, “No more.”

A Vibrant Ceremonious Parade

Next comes the parade. A dozen different bands begin to warm up. The line of march comes from two directions, then blends into a single line passing houses, cafés, taverns, churches, and groceries. The onlookers are crushed together on the sidewalks. The hapless local cops, Madeiran Barney Fifes, feebly attempt to keep viewers on the walkways and out of the marchers’ path.

A sledge hauled by two men pulling on ropes is laden with wine barrels as well as a middle-aged woman in a chair, inexplicably sewing. Men in white knickers and red belts dance in time with the music. Young girls in straw hats, white blouses, and skirts of green with red trim hold bunches of grapes in baskets and are herded through the streets by their parents. Strong, smiling, good-looking young men march past, balancing small casks of wine on their shoulders. Occasionally a pretty maiden walks by and pours wine into plastic cups for thirsty parade-goers.

A marching girl holds out a bunch of red grapes toward me. I think I’m supposed to pluck one or two grapes from the bunch, but apparently, it’s all meant for me. I’m not ready to grab the whole bunch, though, and it falls onto the sidewalk. The parade-goers around me look on in horror and let loose a collective gasp: “Oooohhh!”

I swiftly swoop down on the fallen grapes, sweep them into my hands, stand, and smile. “It’s A-OK, everybody,” I reassure my neighbors. “No worries. Five-second rule! Kiss it up to God.”

A band consisting mainly of brass instruments plays polkas. A woman with a huge basket of Madeiran bread offers hunks to anyone with the munchies. Everyone smiles and laughs. More wine passes by, casks and casks on sledges pulled by men in white T-shirts, green neckerchiefs, and straw hats.

Book a Two Days Tour in Madeira from 9 am to 5 pm Around the Island

Grape Stomping, Homemade Wine, and a Free Meal

Farther down the street, the grapes that have been plucked are dumped into a large wooden leak-proof wagon. Volunteers remove their shoes and socks, wash and sterilize their feet, and step into the wagon to gently stomp on the grapes.

Many Portuguese wineries still crush their grapes this way because it doesn’t break down the seeds, which can lend a bitter taste to the juice. As I watch, a man hands me a plastic glass of freshly stomped grape nectar. The fruitiness and freshness is almost overwhelming.

At another taberna, I have a glass of vinho seco, the Madeiran homemade red wine that burns as it goes down. A stern-faced matron sets a heaping platter of pasta and sausage next to my wine on the bartop before me. A man standing next to me (no sitting allowed in this bar) is clearly drunk. He engages me in a serious conversation even though he speaks no English and I have no Portuguese.

My glass of wine costs 70 cents. Everyone pays as they go. When your drink is set before you, you settle up. Nobody runs a tab. The pasta and sausage are complimentary. The men at the bar, friendly enough, keep looking at me sideways, saying something about “Inglês, Inglês.”

I order another glass of the homemade wine, which a shy young woman pours from an aluminum pitcher. I wouldn’t have been surprised if she’d poured it out of a bucket. Her mother (they look alike, apart from their 20-year age difference) brings me another plate of pasta and sausage.

The Madeirian Tradition Continues

Back on the street, music, smoke from the open-fire barbecues, and the smell of stomped grapes are in the air. Tradition: from the men drinking homemade tinto at the cafés, to two-year-olds dressed in traditional Madeiran costumes, to the butchers cutting hunks of beef for espetada as they have for centuries, to the man blowing the conch shell to warn the crowds that a sledge is sliding down the road, laden with freshly picked grapes. Tradition.

The church bells peal as if a princess has just married her handsome lover. Stunning longhaired young women in peasant dresses pour free wine to entice buyers to look at the wares in their fair booths. Fat husbands hold three-foot-long skewers of barbecued steak, pluck off a piece, and tenderly offer it to their wives.

All at once I realize that everything I love about Madeira is right here in front of me—the amiable locals, the huge portions of full-flavored food, the winding cobbled streets and tilting old houses, the wine and the poncha, church bells, brass-band marches, and the long views from the heights out to the blue, blue sea. I stop what I’m doing and, at least for the moment, revel in the delicious weight of centuries.

Sagres Vacations organizes individual and group tours to Spain and Portugal, as well as half-and full-day excursions. The tour operator has planned another wine tour, including the Câmara de Lobos Harvest Festival, for fall 2024.

Read More:

- You’re Pronouncing it Wrong: Why the Caribbean’s Best Kept Secret Isn’t What You Think - July 8, 2025

- The Gentle Art of Doing Nothing Isn’t Easy in Providenciales,Turks and Caicos - January 21, 2025

- Seeing the Canary Islands Under Full Sail - May 10, 2024