A Day At the Park

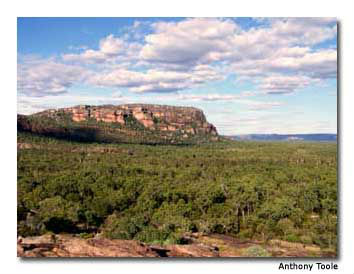

Everything here is big: the birds, the trees, the red rocks. From high viewpoints, the wilderness of eucalyptus forest reaches into a distance limited only by the abrupt wall of the 1,312-foot (400 km) Arnhem Escarpment.

Even the span of a spider here matches that of my hand.

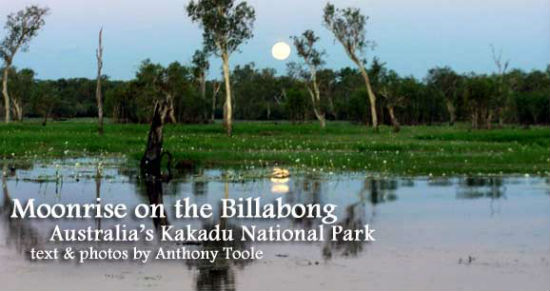

Yellow Water Billabong was no different, though at a first glance it appeared nothing more than a broad river.

The boat meandered through half-submerged trees, freshwater mangroves (Darlingtonia) and a huge acreage of water lilies.

Further expanses of water opened out around each bend, and as the first crocodile drifted silently across the bow we realized we were in the middle of a vast wetland, and that the nearest dry shore was a long way off.

Visiting Kakadu

Stretching 62 miles (100 km) east to west and double that north to south, Kakadu National Park is Australia’s largest national park, a Ramsar wetland (a wetland of international importance) and a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Big as it is, Kakadu is not a place to see at a gallop, and we had taken two days to get this far.

Kakadu has been inhabited by humans for probably 50,000 years, and was almost certainly one of the first areas in Australia to be settled by the Aboriginal peoples.

It plays an important role in their creation myths, those wonderful, richly textured stories that incorporate the physical landforms, the birds, animals, fishes and their relationships with the settlers.

At places within Kakadu such as Ubirr and Nourlangie, these myths are exquisitely illustrated in rock paintings, which give a unique insight into Aboriginal culture and history.

The traditional owners manage the national park jointly with the Australian government’s Department of the Environment and Heritage.

Way to Kakadu

It is a wilderness cut by only two main paved roads: the Arnhem Highway, from Darwin to Jabiru, and the Kakadu Highway, from Jabiru to Pine Creek.

A short paved road north to Ubirr and the border with Arnhem Land is impassable in the wet seasons (or restricted to 4-wheel-drives), as are the unpaved roads that are generally navigable only by 4-wheel-drive vehicles.

We booked our campervan into a campsite in the tourism area of Cooinda and awaited the small canopied boat that would take us on a late afternoon trip on Yellow Water.

Kakadu contains the entire catchment of a major river system, the South Alligator.

It also encompasses the smaller West Alligator and much of the Wildman River; the northeast edge of Kakadu is divided from Arnhem Land by the East Alligator.

In the monsoon season, the floodplains cover hundreds of square miles.

Our campsite had been inundated less than two weeks earlier. As the dry season advances and the waters shrink, the wildlife, including 2.5 million birds, become concentrated into the resulting billabongs.

The Journey Continues

As our boat left its moorings, a flock of magpie geese crossed the sky. To either side of us, an enormous carpet of water lilies stretched toward distant trees.

Egrets and tall jabirus (storks) tiptoed through the vegetation. Darters decorated half-submerged logs, wings outstretched, as immobile as statues.

Pied herons gazed into the water, searching for a meal among the roots of the mangrove.

We learned that there were 30 or 40 bird species in the Yellow Water region. During a year, more than 280 species of birds have been recorded in Kakadu as a whole.

This represents one-third of all Australia’s birds. In addition, around 50 kinds of fish swim throughout Kakadu, as well as two species of crocodiles — freshwater and the larger and more dangerous saltwater.

We spotted our first “salty,” an 11-foot (3.5-4 m) saltwater crocodile, in about 10 minutes.

Over the next hour we came across another six, some gliding through the water, others resting on patches of mud among the trees.

Three weeks earlier, when the water was 8 feet (2.5 m) deeper, only two crocodiles had been seen. Now, the depth had fallen to 3 feet (1 m), and shrinkage of their habitat had brought 15 or 20 into Yellow Water.

In another month, the area over which we now sailed would be completely dry, and the crocodiles would have retreated to the muddy remnants of scattered billabongs.

Seeing the Amazing Scenery

We passed beneath a white-bellied sea eagle, perched magisterially on a high branch, unperturbed by our proximity.

A whistling kite flew over us, carrying nesting material, and settled on a tree.

We sailed away from the water lilies and into a flooded jungle where large trees, tinted pink by the light of the sinking sun, stood in the water.

A sacred kingfisher, adorned in turquoise plumage, landed on a stick, but flew away as we approached.

The boat passed out into open water once again. The sun had now sunk behind the trees to the west, which became black shadows against a background of an increasingly fiery sky.

The reds and oranges of the sky reflected onto the water, giving it an eerie luminosity.

Then something magical happened.

The sky to the east grew dark, yet the raft of lilies and the trees shone with something resembling an alpenglow. The boat slowed and began to drift in silence.

A silver glimmer, the topmost curve of the moon, peered tentatively through a dip in the tree line, before disappearing behind taller greenery.

It reappeared, and though it seemed not to move, in little more than a minute, it was above the trees and opening a gap, which increased noticeably while we watched.

The conversation receded to a whisper, consisting mostly of gasps of astonishment, just audible against the staccato click of cameras and the soft lapping of the water against the sides of the boat.

As the moon rose, its reflection drifted clear of the lily field and acquired its own independence, flickering, fragmenting and changing shape with the line at the edge of the lilies and the ripples on the surface.

Over a period of several minutes, the sky darkened and the sharp boundary between vegetation and water faded and vanished.

Ending Our Journey

The moon rose higher and the first stars appeared. Almost imperceptibly, the magic quietly subsided to nothing more than that of a beautiful tropical night. Yet the effect on us lingered.

We returned to the mooring half-an-hour later than scheduled. As we stood in the pitch dark and sticky heat, awaiting the shuttle bus for the short trip back to the campsite, nobody complained.

Conversations were muffled. An owl hooted in the trees nearby. And the Milky Way glowed like a vivid white streak across the profound blackness of Space.

Kakadu National Park

www.environment.gov

- What It’s Like to Live as an Expat: Lake Chapala, Mexico - April 18, 2024

- Top 5 Spots for Stargazing in North Carolina - April 17, 2024

- The Low-Key Magic of Ghent, Belgium - April 17, 2024