Oh, how we devoted travelers love to return home and boast to our friends that we’ve been to the ends of the earth. However, standing on the Mitad del Mundo (translated from Spanish as “middle of the world”) brings its own bragging rights. But there are two lines near Ecuador’s capital of Quito, claiming to represent the equator. Which one is right? I decided to find out.

The modern-day marking of the line dividing the northern and southern hemispheres can be traced to the First Geodesic Mission. It was a French-led expedition, which arrived in 1736 in the Spanish territory of Quito. In 1936, a monument was constructed to observe the bicentennial of this mission. Two relocations later, the tower can be found about 14 miles (23km) north of Quito, near San Antonio de Pichincha.

The new monument is a “super-sized” re-creation of the original. Standing just under 100 feet tall (30 m), it is an imposing semi-obelisk made of iron and cement, and coated with polished stones from a neighboring mountain.

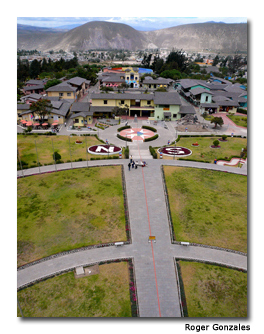

It is crowned by a giant globe, approximately 15 feet (4.5 m) wide and weighing a solid 5 tons. The monument stands in the center of a circular lawn with markers for each of the cardinal headings (North, South, East and West).

It’s a sunny, warm day in September as my friends and I stroll around the lawn, soaking in the pleasant surroundings while crossing the equator from south to north, then south again. I know there’s nothing magic about this particular spot, and yet I feel we’ve circumnavigated the earth in a matter of minutes.

The most popular photo-op is at the “E” marker. Here we take pictures of one another with our arms splayed out wide, the obelisk looming in the background, and our feet straddling on each side of this alleged equator. With the mandatory tourist photos out of the way, we decide to visit the ethnographic museum inside the monument.

The museum uses mannequins, clothing, rafts, hunting and farming equipment, paintings, photos and placards to illustrate the various groups of indigenous people that have resided in the diverse regions of Ecuador. The temptation to snag the multi-colored hats and shawls from the displays and try them on is almost overwhelming…. almost. Overall, the exhibit is a bit dry, so we briskly move through the remaining floors and head for the exit.

The equatorial monument resides in a locale named Ciudad Mitad del Mundo or, in English, Middle of the World City. We wander about this tourist complex that replicates a Spanish colonial town. It’s a close approximation, assuming colonial towns typically had planetariums, snack-bars with pre-packaged ice-cream treats and shops selling “I stood on the Equator” t-shirts. My friends are ready to leave, but I insist that we see the “other” equator.

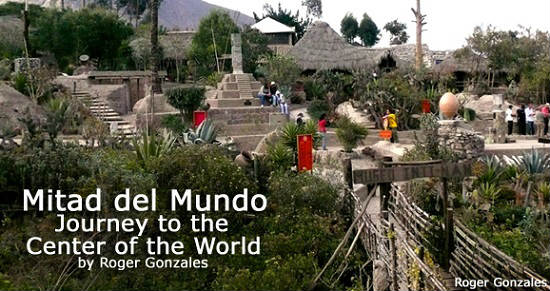

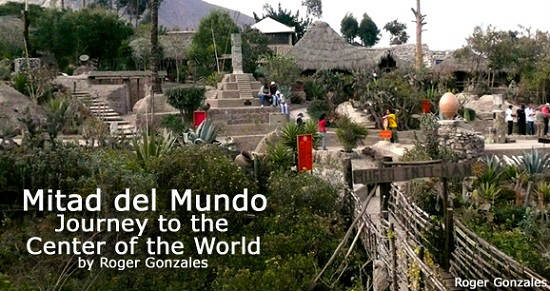

About 820 feet (250 m) from Ciudad Mitad del Mundo and tucked away farther from the main road is the open-air museum Museo Inti-Ñan, translated from the indigenous Quechuan language as “Path of the Sun.” Scanning the museum, I see several wooden huts, a small pyramid, totem poles and other attractions, all spaced out between a variety of native plants, bushes and trees.

A sweet, but somewhat serious young woman named Nancy is assigned to be our guide for the hour-long tour. Nancy slowly walks us through different reconstructions of dwellings historically used by various cultures from this region.

Each edifice comes with its own story about that culture’s spiritual beliefs, as well as tidbits regarding their technologies. In one particular home, there is a designated entrance with a separate exit. Nancy explains that this prevented visitors with “bad energy” from leaving it in the house.

Other features include a model scale of the Galapagos Islands, a mini-natural history museum and a shrunken head encased in glass. The gray, deformed head with the eyes and mouth sewn shut is horrifying, yet I can’t look away. Next, we each don a traditional feathered hat and try blowing a dart through a blowgun. None of us can suppress our laughter knowing how ridiculous we must look. When it’s all over, we men hang our heads in shame, after missing the cactus leaf target that each woman managed to hit.

Finally, we head toward what has been advertised as the “real” equator. This equatorial line was calculated using a Global Positioning System (GPS) device, similar to the ones used in cars. Therefore, this is a more precise estimate of the actual equator. I had to admire that the French measurement is only some 700 feet (213 m) away, given that it was calculated about 270 years ago.

Along the line there are some native chronological devices such as an agricultural calendar that indicated equinoxes and solstices that were critical to the harvest seasons. This is all just the appetizer to the main course, which is the set of “scientific experiments” supposedly proving we are really on the equator.

The first experiment involves a sink full of water. I watch amazed as, when the plug is removed from the sink on the equator, the water flows straight down. Nancy then moves the sink just a meter or so onto the northern hemisphere and then refills it. This time when she pulls the plug, the water flows counterclockwise. It flows the opposite way when the sink is moved to the southern hemisphere.

Next we try our hand at balancing an egg on the head of a nail, supposedly made easier because of the lack of certain forces at the equator. With a little luck and a little patience, all but one of us succeed and receive our official certificates.

Luckily, none of us knew at the time that most scientists have rebuffed these types of experiments as nothing but sideshow-like charades. There are, however, a couple of other tests that left me speechless, and that I have not yet been able to debunk. But those will remain secret so you can be surprised when you go.

“OK, guys, my curiosity is satisfied. What’s for lunch?” I ask my Ecuadorian friends.

“Well, you have to try some cuywhile you’re in Ecuador.”

“Sounds great – let’s go. By the way – what’s cuy?”

“I think you call it ‘guinea pig.’”

OK — maybe I’m not ready for lunch after all.

If You Go

Mitad del Mundo

$2 to enter the complex; $3 more for the museum ($1 for kids)

www.equaguia.com

Roger Gonzalez is a US based travel writer. He spent several months in 2007 writing for the non-profit South American Explorers (SAE) in Buenos Aires, Argentina. He finished out the year by traversing the “Gringo Trail” through Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, and Argentina.

- Life of a Champion: Exploring the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville - April 19, 2024

- What It’s Like to Live as an Expat: Lake Chapala, Mexico - April 18, 2024

- Top 5 Spots for Stargazing in North Carolina - April 17, 2024