Editor’s Note: We share travel destinations, products and activities we recommend. If you make a purchase using a link on our site, we may earn a commission.

We were floating in the blue-green waters where Bahia Honda reaches the sea. It was 8 am on the third and last day of our trip to La Guajira Peninsula in Colombia. We had taken a motorboat around the bay to this beach where a jeep would pick us up and take us back to Rioacha.

As we left the bay the water changed from dark green to a more transparent shade. But the contrast with the dark yellow sand remained. We had seen pink flamingos, colorful birds, green mangroves and golden cliffs. The day was beginning and we were, once again, in awe.

The People of La Guajira, Colombia

This is the land of the Wayuu people. A nomadic tribe who were never subjugated by the Spanish. They remain, to this day, proud, serious, borderline hostile but beautiful people. Just like their land. They make a living herding goats, weaving, fishing and, more recently, with tourism.

We had departed from Rioacha, the capital of the La Guajira district. Four travelers and Fredy, our driver. After an hour on paved road we entered a dirt path following the train track that connects the coal mine of Cerrejón to Puerto Bolivar.

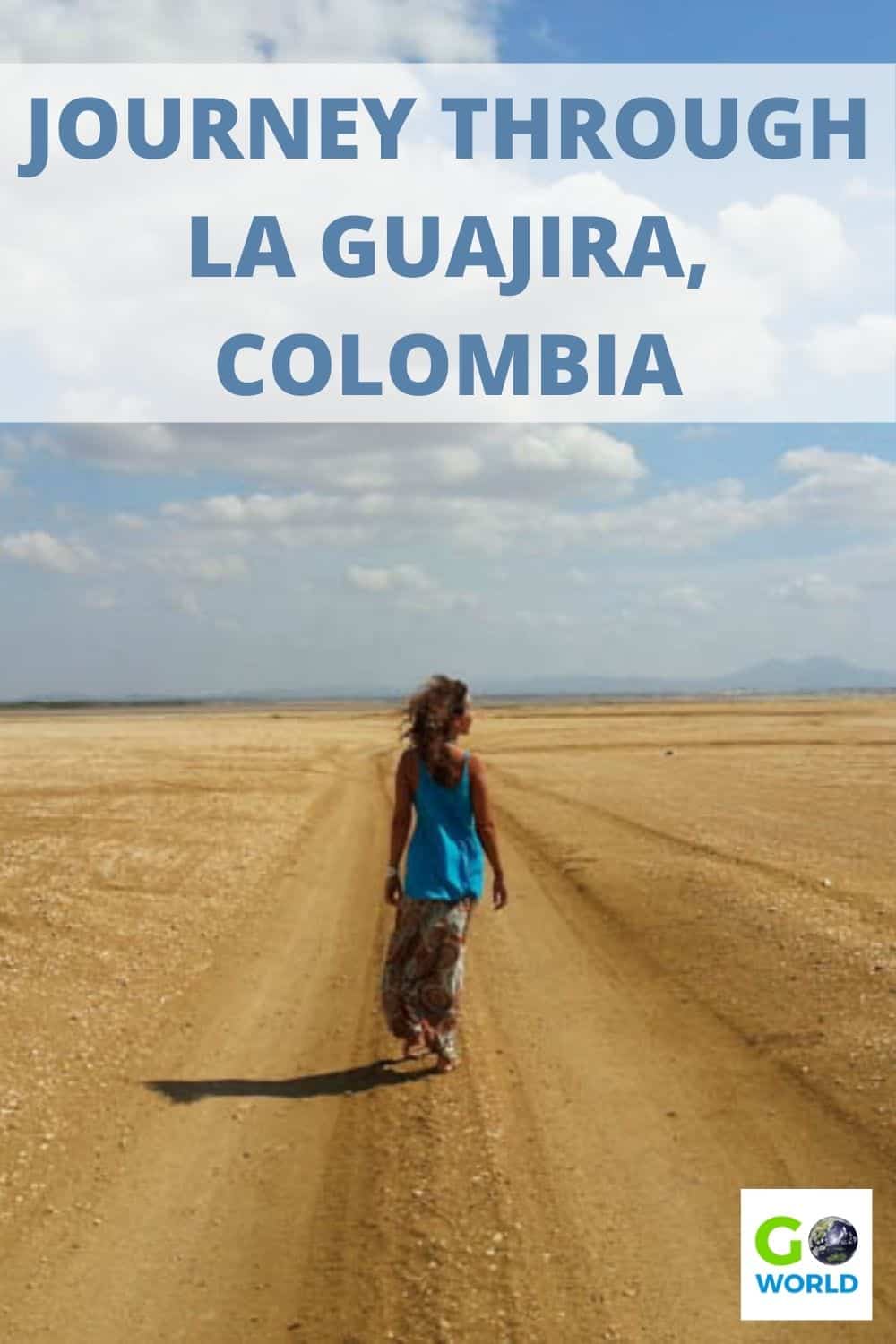

The lush green vegetation that characterized the north coast of Colombia up until Rioacha was replaced by yellow earth, occasional green cacti and grey, dry shrubs.

After a while, the track became harder, full of holes and the landscape even more desolate. We seemed to be driving towards nowhere. We had reached the Upper Guajira desert.

Proof of life came from the ropes stretched across the road. Children held them at each end. Fredy sounded the horn, slowed down, but tried not to stop. He explained that the children are making road stops to get candy, or money, from the tourists.

He had been instructed not to stop or give anything as that would only contribute to the problem. I nodded in agreement. Not only is it a commodification of visitors, but it is also not safe. Children have been hurt because they stand too close to the road holding the rope.

La Guajira, Colombia is in a state of emergency from the lack of water and these children may need many things they cannot get because of the difficult life they lead here. Candy is not one of them.

Village of Cabo de la Vela

After 20 minutes we saw green in the horizon. The sea. There was absolutely no vegetation around, just a brownish plain under our wheels. As we approached, the car ran parallel to the water, a few meters away. The desert to our right, and the sea to our left. I had never been to a coastal desert before. It felt surreal.

That night we would be sleeping in Cabo de la Vela. The village named after the nearby by cape was originally just a Wayuu fishing community. However, now it is a popular kitesurfing and beach destination.

It consists of a dozen houses on both sides of a dirt road that runs parallel to the seashore. The contour of the land forms a blue bay, with the cape at the end of it.

Most of the companies operating in the area have connections to the Wayuu. It is in their rancherias that accommodation is provided. Options are traditional hammocks, the chinchorros, under a palm leaves rooftop, or in very simple cabanas made of yotojoro, the heart of a big local cactus.

There is no running water and electricity is provided by generators or solar panels. During our visit in November, there were almost no tourists, but December and January bring crowds of Colombian visitors.

We dropped our backpacks at the rancheria and enjoyed a small rest from the bumpy three-hour ride. Then we drove away from the village to explore the surrounding area.

The Colorful Coastal Desert of La Guajira

At the top of the cape, our hair was flying in all directions and our skin was sprayed with saltwater rising from the clash of waves against cliffs. All we could hear was the howling of the wind and the gushing of the sea.

I sat down, enjoying the brightness of the colors. Greenish-grey rocks sprinkled in rusty yellow, orangey-yellow sand, cyan blue sky, turquoise blue water and white foam waves. The strength and contrast of the colors were something that never ceased to amaze me.

From the top of Pilon de Azucar, a 100m hillside, we could see the path we had taken in the morning and the whole of Upper Guajira beyond. Mountains in the distance, then miles of vastness.

The whole area of Cabo de la Vela, Jepira, in Wayuu, is sacred for its people. It represents the place where the spirit of the dead wander when they begin their journey to the unknown.

Pilon de Azucar is one of the spots they pass by. On top of it is a statue of Our Lady of Fatima and behind it someone graffitied an eye. Old and new beliefs mingle in the wind. It seemed strangely appropriate.

Sleeping in Hammocks and Watching the Sunrise

Dinner is included in the price of the tours. You can enjoy good fried fish or goat. We decided the extra 20000COP ($6 USD) for fresh lobster was worth the splurge.

One hour later we were cracking legs, sucking heads and laughing at our buttered fingers and lips. We were feeling full and happy under a sky full of stars. Lights went out at 9 pm and we sunk into our hammocks, cradled by the breeze and the rustling sound of the sea.

I woke up to a pink sky. By the time I walked the 10 meters to the beach, it had gone from pink to orange and the sun was just over the horizon. Everything was tinted gold. The sea was a mirror, the trees were black silhouettes and pelicans flew by grazing the water.

There were five or six people on the sand. We whispered good morning and sat down at different places, in silence, facing the sun. It is said the spirits who wander here can talk to us in our dreams. I don’t know what we all dreamt of that night, but it must have been good.

Exploring the Remote Peninsula & Taroa Beach

The second day was spent making our way north across the Peninsula. First on a path surrounded by cactus, grey stones and dry grey bushes. Then crossing miles and miles of sandy, flat desert with nothing in sight but the undulating hot air. Unlike Cabo, there is no public transport and tourism is just beginning here.

Sometimes we would see a couple of rancherias and Fredy would tell us the name of the village. They looked deserted, but every now and then people would pass by, walking or riding bicycles.

There were no cars in sight other than the occasional truck passing us. From my air-conditioned seat, I felt a knot in my throat passing by a teenager cycling with two large plastic containers on the back. “Água” Fredy pointed.

Water in this area is stored from the rain in big containers, but it hasn’t rained in many months. Drinking water comes in trucks from Rioacha, at very high prices.

We reached Taroa beach at 2 pm. The jeep stopped at the base of the 60 meters dunes. We couldn’t see past the sand. It flew around and hit our skin like needles. From the top, the sea opened in front of us.

The dunes tumbled down straight into the water. We rolled and played around in the warm waves for an hour feeling, yet again, blessed to have such an incredible place all to ourselves.

The Rocky Road to Punta Gallinas

From there to Punta Gallinas, the northernmost point of South America, the road got even bumpier. There were rocks all over the path.

The point itself is a stretch of sand with an abandoned house, a white and red light post and a garden of cairns on the seashore. We stacked small stone contributions to one of the cairns and drove on.

Our stay for the night was in a rancheria atop a cliff with Bahia Honda on one side and the sea on the other. A scenery of dark green water, golden yellow sand, green mangroves, cactus and shells in unlikely places, a testimony of different water levels.

A roaring wind never allowed for silence but relieved us from the scorching heat. That night the stars were even brighter. I sat by myself pondering on how lucky I was to be there.

I also wondered how the region would develop in terms of tourism and feared for its effects. I wished upon one of the shooting stars it wouldn’t ruin the beauty that had caught my breath so many times in so few days.

Author Bio: Filipa is a Portuguese writer and travel leader. She loves the world but has a soft spot for Latin America and the Argentinian accent in particular. You can find her traveling, researching and volunteering on sustainable projects, and searching for stories about people and places that inspire change and empathy towards others.

- Top 5 Spots for Stargazing in North Carolina - April 15, 2024

- The Low-Key Magic of Ghent, Belgium - April 15, 2024

- Swiss Travel: A Guide to Exploring Switzerland by Train - April 15, 2024