Go World Travel is reader-supported and may earn a commission from purchases made through links in this piece.

Our taxi driver greeted us enthusiastically. “Welcome to Dublin!” As he drove us, John told us about his Belfast childhood and the times of trouble.

He spoke of being locked away for three years simply for being on the wrong side of a wall (separating Catholic nationalist communities from Protestant loyalist neighborhoods) at the wrong time. After he and his wife had children, they decided to move to Dublin in the Republic of Ireland.

“Couldn’t raise our daughters with vengeance in their hearts,” he said, his gaze fixed on the bridge before us as we crossed over the Liffey River to the north side. “It’s hard to let go, but it has to stop somewhere.”

He asked us to make him a promise before dropping us off at our lodge. “While you’re seeing the sights, talk to the people. Listen to their stories. The best part of Dublin is the people.”

Big Fun in this Little Museum

Back on the south side of the Liffey River, across from St. Stephen’s Green, where Oscar Wilde reclines atop a slab of granite and statues, sculptures, and busts honor the literary likes of James Joyce, W.B. Yeats, Lord Byron, and Oliver Goldsmith, we came to a street of stately Georgian townhouses. One of them was home to “The Little Museum of Dublin.”

Our guide, Claire, sported a mischievous smile. “Prepare yourselves for a time-traveling adventure, guided by the trinkets and treasures of everyday Dubliners.”

Planning a last-minute trip to Ireland?

Top Experiences and Tours in Ireland:

- See the sights with a tour of Dublin: Cliffs of Moher, Kilmacduagh Abbey, Wild Atlantic way and Galway

- See a castle with Blarney Castle Day Tour from Dublin Including Rock of Cashel & Cork City

- Explore more with a Game of Thrones Studio Tour Admission Ticket

Where to stay in Ireland:

- Find accommodation with Booking.com

- Get a rail pass through Rail Europe

- Find Bus, Train, and Flight tickets with one search through Omio

She guided us through the rooms of items with wit, charm, theatrics, and a healthy dosage of clever puns. “This plaster cast,” Clair pointed us to James Joyce’s death mask, “is the closest you’ll get to a Dubliner ever truly being lost for words.”

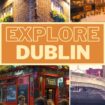

A bust of Jonathan Swift shared the mantle with a “My Goodness, My Guinness” figurine and a dozen other items. Ducks stood in a row along the top of a windowsill and dolls and figurines stood here and there. A red mailbox turned green before our eyes, exemplifying how the Republic of Ireland, rather than replacing all of the British post boxes, simply painted them green. “Ireland was going green long before it was fashionable.”

Movies, Posters, and Exciting Exhibits

In the next room, movie posters for The Quiet Man and Darby O’Gill and the Little People promoted an image of Ireland once imagined by Americans: a land of emerald hills, charming villagers, and mischievous leprechauns. Other pictures and posters conveyed the real Ireland—it’s triumphs and struggles.

Dublin’s 1000th birthday in 1984 wasn’t just marked by grand celebrations, but also by a quirky souvenir: milk bottles with Dublin’s coat of arms on the front. Many of these bottles were kept as keepsakes, even transformed into table lamps.

In one corner, Claire told the tragic story of the “Magdalene Laundries.” These former workhouses, run by the church under the guise of charity, placed women in virtual slavery. These became home to “fallen” women: unwed mothers, girls born out of wedlock, the morally questionable in need of redemption. Photographs and everyday objects—a sewing thimble, a worn hairbrush—made their stories real.

One room was dedicated to William Russell, editor of The Irish Times, his legacy preserved in editorials and photographs. Another celebrated U2 with music posters, record covers, and a statue of Bono leaning on a mantle.

Each exhibit felt personal, curated by the very people who lived and breathed Dublin’s history. In fact, every item in the museum was donated by a resident of Dublin—by people who wanted to be a part of telling the city’s story. Claire brought to life what the taxi driver said: “The best thing about Dublin is the people.”

A Visit to Kilmainham Gaol

When we arrived at Kilmainham Gaol (or Jail), now a memorial museum, a stout man (who looked as much like a prison guard as a tour guide) welcomed us.

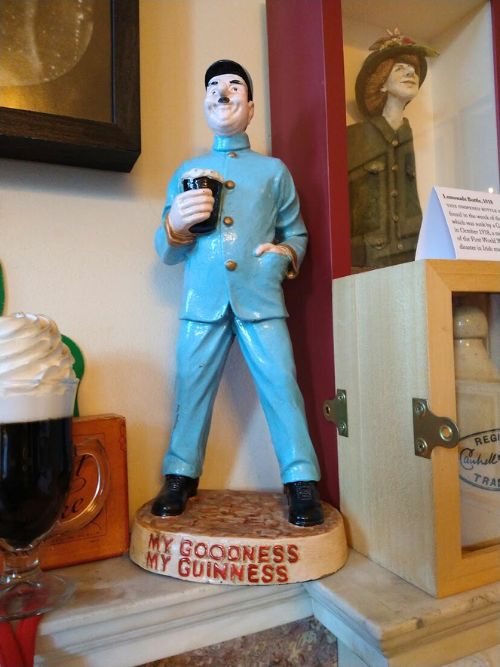

Silent hallways swallowed us. Sunlight filtered through narrow windows. The names of revolutionary figures imprisoned here crowned the cell doors. In an enormous interior hall, sunlight pouring in through the glass ceiling, our guide explained that only five or so prisoners at a time were allowed out of their cells for meals or exercise as a means of control.

“This is where it happened,” our guide said as we stood in the outdoor courtyard within the prison walls. “The Rising had faltered, its leaders captured and brought to these very walls. Fifteen men, deemed the instigators of the rebellion, were sentenced to death by firing squad.”

The guide looked at each of us directly as though we were sentenced, then continued. “Over the next nine days, eleven more faced the same fate. Éamon de Valera, standing where you stand now, declared, ‘The Irish people have a right to fight for their freedom and it is their duty to do so.’”

The execution yard is now a garden of remembrance. Back inside, we walked through exhibits about the Gaol’s past, about its prisoners. And about its last prisoner and future president.

Éamon de Valera was released in 1924 when the prison closed. He went on to become President of Ireland from 1937 to 1945 and again from 1959 to 1973. He was involved with the Gaol’s preservation due to its historical significance, even returning to the Gaol in 1962.

Someplace to Write Home About

Dublin’s general post office, or GPO, is located along O’Connell Street, one of the main thoroughfares on the north side of the river, just next to the iconic Spire that towers above. This isn’t just any post office; it’s the former headquarters of the 1916 Easter Rising and a symbol of Ireland’s fight for independence in the early 1900s. And now, it is home to the GPO Museum.

Interactive exhibits painted a vivid picture of the Easter Rising. Touchscreens flickered with the faces of revolutionaries, their determination etched in pixels. Videos pulsated with scenes of Dublin in the throes of rebellion, black and white images carrying a haunting immediacy.

Dublin’s Intense History of Oppression, Famine, and Revolution

In the heart of the museum, a short film used an immersive approach to bring us into the discussions and debates during the revolution. After getting to know the heroes and what they fought for, lighting drew us to the museum’s prized possession hanging on the wall behind glass: an original print of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic.

“Irishmen and Irishwomen! In the name of God and of the dead generations from which she receives her old tradition of nationhood, Ireland, through us, summons her children to her flag and strikes for her freedom.”

The words are inspiring in the same way as the words of America’s Declaration of Independence or Preamble to the Constitution. Only these words don’t come from hundreds of years ago. For people visiting, it’s sometimes a revelation to understand the revolution here—and Irish independence—came little more than a century ago. And some, North of Ireland, fight for it still.

Dublin is a place where intense history of revolution, of famine, of oppression, and of independence feel fresh, where such things still linger in the memories of millions of people with parents and grandparents who had, not long ago, been able to talk about such events from personal experience. At the GPO Museum, this experience was brought to life.

Get Lost in a Pint

Guinness has been woven into the fabric of Dublin since 1759. Arthur Guinness was determined to create a superior stout for locals to enjoy, no matter how long the commitment, so he took out a 9,000-year lease, and set in motion a legacy that would see his stout conquer the world. The Guinness Storehouse, once a fermentation plant, now stands as a seven-story testament to that legacy, each floor bursting with Guinness stories and experiences.

Interactive exhibits brought history to life, from holographic brewers explaining the malting process to vintage Guinness advertisements—from toucans and seals to lions and thirsty workers—showcasing Dublin’s transformation alongside the stout. We were treated to a lesson in how to properly drink a stout (taste included) and entered a room where the individual elements were broken down for us to smell and recognize.

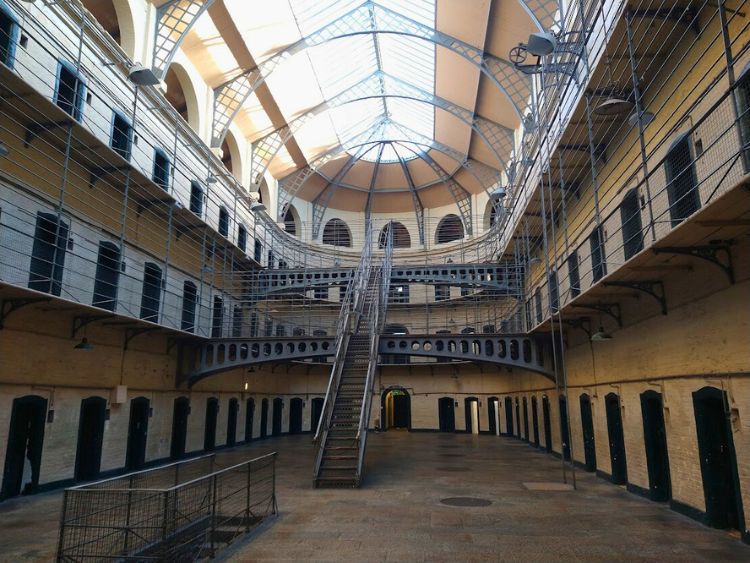

Guinness’s newest attraction: the STOUTe experience. With a souvenir snapshot and a touch of artistry, our faces were printed onto the creamy head of freshly poured stouts. We laughed out loud as we clinked our pint glasses and proceeded to drink one another. Because we were drinking our stouts properly, our images remained along the creamy head until they were at the bottom of our glasses.

The Epic Gravity Bar in the Guinness Museum

The grand finale to this experience awaited on the seventh floor. After being treated to a traditional Irish pub song, we ascended to The Gravity Bar, offering a panoramic, 360-degree view of the city. We approached the bar and ordered two more pints of Guinness to top off our visit.

In the Gravity Bar, we were ourselves in the head of an enormous pint of Guinness—the center of the museum is in the shape of an enormous, seven-story pint glass with the window view of Gravity Bar serving as the stout’s creamy head. For the second time of the tour, we found our faces in a pint of stout. We clinked our glasses drank, and enjoyed the view of Dublin below.

Topping Off an Epic Visit

EPIC is an interactive journey through the rich tapestry of Irish emigration. It educates visitors about the historical, social, and cultural factors that drove millions to leave Ireland, while celebrating their contributions to the world across various fields like music, literature, sports, and business.

The EPIC Museum owes its existence to Neville Isdell, an Irish emigrant himself who went on to become the chairman and CEO of Coca-Cola.

Passports are given to each visitor to stamp at more than 20 exhibits throughout the experience. Our passports soon sported colorful stamps from across the museum, including exhibits on music, dance, sports, and culture. Literature came alive, with interactive displays celebrating the likes of James Joyce, W.B. Yeats, Samuel Beckett, and Oscar Wilde, their words transcending borders and continents.

But the journey wasn’t just about the famous. The “Workhouses” exhibit, with its stark black and white photos, told of the hardships many Irish emigrants faced. We learned of the struggles endured by countless Irish men and women, their resilience keeping them on their paths. A display showcased the contributions of immigrants in building canals, railroads, and cities across the globe. In one exhibit, I found myself posing for a mug shot, ready for a stint in prison.

By the time we reached the final stop, our passports were a vibrant mosaic of stamps, each representing an experience in the museum. EPIC—like Dublin—wasn’t just a place to visit. It was an experience.

“The best part about Dublin is its people,” Nataliya said as we left, echoing our taxi driver’s words.

If You Go:

There are countless flights from U.S. cities to Dublin; we opted for an affordable Icelandic flight from Baltimore-Washington airport to Dublin with a layover in Reykjavik, Iceland.

There are many lodging options, and most tourists opt to be south of the Liffey River. However, there are safe, clean, and affordable options in Georgean townhouses on the north side of the river—and close to the Spire, which makes for a great landmark to hone in to home every evening. While it’s true that the Spire is also known as “the Stiletto in the ghetto,” most of our guides and the locals we spoke with said that they lived north of the Liffey. Gardiner Lodge provided a full Irish breakfast each morning and a very helpful, 24-hour front desk clerk.

Read More:

Author Bio: Eric D. Goodman is the author of seven books. His most recent is Faraway Tables, a collection of poems focused on travel and a longing for other places. His novels include Wrecks and Ruins (set in Baltimore and Lithuania) and The Color of Jadeite (a thriller set in China). Hundreds of his stories, poems, articles, and travel stories have been published. Learn more about Eric and his writing at www.EricDGoodman.com.

- Together at Sea: A Mediterranean Family Adventure - April 27, 2024

- Travel Guide to Colorado - April 26, 2024

- Travel Guide to Croatia - April 26, 2024