We are reader-supported and may earn a commission on purchases made through links in this article.

Had you asked me when I first moved to Egypt whether I’d ever wear a shirt stolen from a dead person, I would have recoiled and questioned your sanity. Or if you’d asked me the street price for an Egyptian tortoise or Vervet monkey, I would have shrugged in bewilderment. Then again, I never thought I’d ever be doing most of my shopping in a cemetery, or bargaining for used clothing and endangered animals.

Shortly after graduating from college, I decided to move to Cairo, Egypt to study Arabic as well as to spread my wings and live abroad for a few years. In the process, I discovered a market and a way of shopping that defined my experience as a whole.

In the massive urban sprawl of Cairo, there are five major cemeteries that were at one time located on the outskirts of town. But because of the rapid expansion of Cairo over the last few decades, these cemeteries have slowly become more and more central.

Due to housing shortages, overpopulation, and the rising cost of living, today the cemeteries have become home to over 5 million of Egypt’s urban poor. They have migrated there in droves, usually taking over in squatter fashion, grabbing the free real estate before someone else can move in, and making the tombs of the dead into residences for the living. These vast tracts of overcrowded cemeteries that lie along Cairo’s Moqattam Hills have become known collectively as the “City of the Dead,” a mysterious, unknown, and foreboding place for both foreigners and Cairenes alike.

As one passes by the tombs made into houses, you see children dressed in threadbare clothing standing in the doorways and playing in the garbage-strewn streets. You notice the creative use of cement coffins inside the tombs that serve as everything from ironing boards to dinner tables, from benches to beds. Laundry lines crisscross the spaces, strung up between gravestones, and television antennas are propped up on the low, flat roofs.

Although some of the earlier residents have illegally spliced wires from nearby mosques and run electric wires to their tombs, most residents do not have the luxury of lights, TVs or telephones. And since people living in the tombs are technically illegal squatters by Egyptian law, there is also no sewer or trash service. Piles of garbage are on every street corner, while some alleys run with raw sewage. The chief source of income for these people is a large market that occurs every Friday morning, open to all who have something to sell, with no vendor fees or laws to regulate what is sold.

Shopping in the suq al guma’a or “Friday Market” in Cairo’s City of the Dead is an event that draws tens of thousands of Cairo’s poorest every week to a place where they can both buy and sell almost any kind of junk, trinket, or treasure, at a price that they can all afford. It also occasionally draws one or two Western-weary, slightly adventurous, financially struggling Arabic students, such as myself.

Even on my meager student’s stipend, I could feel like a king for a day.

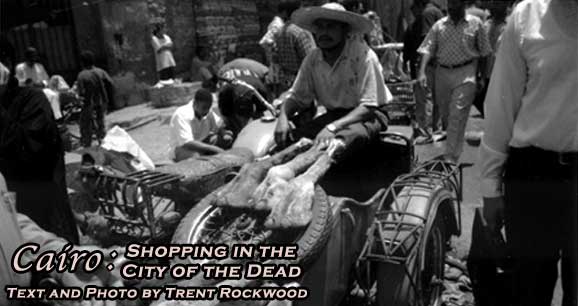

As I jump off a minibus, which slows down only slightly to allow the frantic passengers to simultaneously jump on and off, I find myself at the front entrance of the infamous Friday market — a large unpaved street that winds for about a mile (1.6 km) through the tombs of the now inner-city graveyard. I am at once hit by smells, sounds and images that are almost overpowering — a motorcycle stacked with dozens of camel legs sits beside huge buckets filled with goat, donkey and sheep entrails. Large pails of cow liver and raw fat sit in the sun, while women and men with blood up to their elbows yell back and forth bargaining with potential buyers over the din of the crowd.

“Liver! Stomach! Intestines!” a black-clad woman shouts as she pushes her way through the crowd, carrying a dirty plastic bucket atop her head swarming with flies.

The mass of people is so thick that I am herded into one direction or another almost against my will, and have to step between vendors to get my bearings. This is survival shopping at its best, just as it’s been in this part of the world for thousands of years. Success at finding a good deal here depends solely on one’s aggressiveness, bargaining capability, and craftiness, as opposed to your credit limit, as it is back in my hometown of Washington, D.C. It’s also a refreshing lesson in honesty, as both the seller and I can be completely honest about our intent to fleece the other for all he’s worth.

I pause by the merchants who have spread out their small blankets in front of them to display wares they have picked up out of the garbage or stolen off the streets during the past week — piles of broken toys, smashed remote controls, old plastic container lids, coils of wire, pieces of a computer, here and there an old watch, a magazine — all for a price that even the poorest of the poor can afford. Most of the merchandise is actual bona-fide junk, such as innards of long-outdated typewriters, dented hubcaps, old bed springs, a piece of twine, a broken phone receiver — that they are hoping someone, somewhere has a use for. The vendors start their prices out by sizing you up visually: if you are well-dressed and look like you have money, the price starts high.

“Does this work” I ask, pointing to an old VCR with a smashed display panel.

“Yes, it works,” the man says, brushing the dust off of it with his sleeve.

“Can I test it?” I ask. He looks around at the mud and cement walls along the street and shrugs. I forget that there are no electricity outlets for miles around here.

“I’ll take that alarm clock there for one guinea,” (about US$ 0.20) I say.

“Are you kidding?” He laughs, “It’s worth more than four!”

“Two guineas,” I say.

“By God, I wouldn’t sell it to my own mother for that!”

I wave my hand and feign walking away.

“Wait!” He says, “May God curse you, take it for three” and shoves it in my hands.

“I can buy a new one for only three and a half!” I counter, and we continue this until a price acceptable to both of us is finally agreed upon, and we both part grinning to ourselves at our shrewdness. Never has shopping been so exiting.

I move on to the used clothing sellers who heap their merchandise into large mountains on top of plastic tarps, with crowds of people digging through them indiscriminately, holding up blouses, underwear, pants, ties, shorts, and socks, yelling out an offer, and then throwing them back to keep on searching.

As I sit rifling through the mound of clothing, a man passing by leans over and says in a low voice, “Don’t touch those clothes, they’re from the dead.” I look at him in disbelief. “They take them off their bodies before they are even cold,” he continues.

Judging from the smell of them, I suspect he’s probably right.

“Why should that stop you?” a nearby woman says laughing. “They don’t need them anymore!”

I had heard from an Egyptian friend that some of these clothes come from charitable organizations in the West, whose shipments are frequently sold by the ‘charitable organizations’ to second parties, who in turn sell them to third parties on the streets. However, other sources of clothes are more dubious. More than one person told me to wash the clothes I bought at the Friday market at least three times.

“When someone dies in Cairo, they do not sit in the grave clothed for very long,” my friend said. “Some,” he continued, “are even taken before they get to the grave.” He explained how sometimes the doorman of an apartment building will often inform his cohorts when a building tenant has died, and before the grieving family has a chance to discover the tragedy, they rush the apartment taking all of the belongings, from the china in the cupboards to the clothes on the corpse.

Despite the warning, I find a great fleece button-up shirt that doesn’t smell too awful, and haggle it down to US$ 2.50 (about 13 Egyptian pounds). I have to throw in another five cents for a plastic bag to carry it in.

Up the street I pass a row of shoe sellers, wondering what one would do with an unmatched single shoe.

“This one almost matches,” The vendor tells me, holding up another single shoe. “They are both black.”

“Yes, but they are different styles,” I say.

“Then let me make you a deal,” he says. “You get one shoe for half-price”

I can hear and smell the live animal market before I reach it. Here, you can find every kind of animal species that survives the trip up from Sudan and Eastern Africa for sale. There are monkeys, hawks, badgers, weasels, parrots, fish, all packed dozens to a cage. I see a large wire container filled five feet (1.5 m) high with desert tortoises, the ones on the bottom clearly being crushed. Most of the animals in the market look to be near death, which doesn’t seem to bother the crowds of kids who are poking at them with sticks and throwing rocks and cigarettes into their cages. I ask how much the desert falcon is, and the seller won’t go down below 80 guineas.

“What do you feed him?” I ask.

“Anything. Bugs, meat, fish, fruit” he says. I didn’t know hawks ate fruit, I say to him, but he is already busy fighting children away from the poisonous snakes with a stick.

Just around the corner is a taxidermist who apparently has a relationship with the animal seller and offers ferocious-looking stuffed versions of the same animals for sale. They look diabolically creepy, fitted with cheap glass eyes taken from dolls, and then given an evil grin with bared teeth or open beak, sometimes with fake blood painted around the mouth. There’s nothing quite as unsettling, I find, as a goose fitted with bloody fangs.

I veer off a side street into the coin sellers’ alley, and start the long and time-consuming process of sifting through bowls or socks of old coins. These are sometimes the most interesting and educated of the vendors, having gleamed a smattering of world history through the collection of their coins and bills, and I make small talk about what I am missing from my King Farouq coin collection.

King Farouq was the last king of Egypt, who ruled from 1936-1952, when he was overthrown by Egyptian nationalists led by Gamal Abdul Nassar. The coins with his image on them are collector’s items.

The inevitable question is posed: “Do you want to see the old coins?” one vendor asks.

What he means by ‘the old coins’ are the Ottoman, Byzantine, Greek, and Roman coins that are illegally pilfered from archeological sites.

“What do you have today?” I ask. A vendor pulls out a leather pouch from his breast pocket, and looking left and right to make sure no undercover policeman might be watching, pours out about a handful of silver and bronze Roman and Greek coins.

I learned the hard way that every coin vendor has both real antique coins and fake ones, and if you don’t learn to differentiate the two early on, you’re liable to buy a complete set of melted down copper wire. He tells me that special requests, such as a coin from the Ptolemaic (332 BC – 30 AD), or the Fatamid (969-1171 AD) period, can be fulfilled in less than a day, and, if I have the money, he can offer me more than just coins. But since trafficking in illegal artifacts carries a jail sentence in Egypt, I politely decline.

As I wander past the appliance section of the market, I recognize old home appliances that I haven’t seen since I was a young child — an old Frigidaire, bathroom sinks with bronze claws, hand-powered washing machines, coal-heated irons, mantles and awnings taken from abandoned 18th century churches and mansions and dusty chandeliers with two or three crystals hanging from them.

Next to these are rows of old and new bikes and motorcycles, some of them with a chain and lock still around the back wheel.

“Do you have the key to the locks?” I ask.

“No, but it is very cheap to cut. You can go to any mechanic’s shop,” the seller says.

As they say in Cairo, what you lose on Thursday, you can find on Friday at the market.

I pass by piles of aging military equipment, gas masks, empty mortar shells, cracked range scopes for Canons and outdated nautical equipment. There are printing presses next to old couches, a rowing machine, piles of cracked records, empty bottles, stacks of ancient postcards, knives, stuffed teddy bears and a saddle for a camel.

The new highway, which was built so that wealthier Cairenes could drive over the cemetery rather than through it, signals the far end of the market and creates the much coveted under-the-bridge real-estate that houses some of the more established vendors such as the antiques dealers, the electronics repairmen, the ‘forbidden’ movie sellers, and one of the oddest markets I’ve ever been to in my life: the dog mating market.

Sectioned off in one small area under the bridge, groups of men and boys bring their dogs of all types and sizes to bargain with one another for the price of a mating. The more handsome and healthy the dog is, the higher the price he fetches. Once the amount is agreed upon, the men form a small circle around the two dogs and watch the ensuing process with almost analytical scrutiny, hands on their chins, nodding their heads in approval at the end of the transaction. I shoulder my way into one of the circles, to see if this is really what it appears to be and make a quick retreat — not finding the spectacle as exciting as the others seem to.

Other sellers wander around with puppies, the results of previous mating sessions, and let buyers feel the dogs’ teeth, muscles and skin before starting to bargain. Most of these dogs go to southern Egypt to be guard dogs for farmers, and many men have made a one- or two-day trip for the chance of mating their dog with the stock of Cairo’s finest.

The market begins to thin out at this point, and I look down at my shoes and hands covered with the fine gray dirt of the cemetery. I smell the burning plastic and garbage odor that permeates my clothes and hair. I head for the bus stop, and as the children that have been following and pestering me for the last three hours start to lose interest and wander away, I can finally take stock of my finds for this Friday. One shirt, probably taken from a dead person, two Mameluke coins (the Mameluke were former Turkish slaves who took power from their masters), possibly stolen from an archeological dig, and an alarm clock that was most likely taken from the garbage — all for just under US$ 3. But the experience of shopping among the dead is almost priceless.

If You Go

The Friday Market occurs every Friday from 8 a.m. until about 2 p.m., under the Moqattam Hills. It can be reached on foot or taxi from the Citadel. Ask for the suu’ al guma’a or you can go by minibus from ma’aadi, a wealthy suburb of Cairo about 5 miles (8 km) south of the city center along the Nile. This is where most foreigners live. Do not bring a lot of money, and do not dress flashy.

Egyptian Tourist Authority

www.egypttourism.org

Inspire your next adventure with our articles below: