Go World Travel is reader-supported and may earn a commission from purchases made through links in this piece.

Hassan turned the paper one way and then the other, he turned it upside down. Smelt it. Licked it. Then ripped it into little pieces which fluttered then rested on the red sand of the dune like dead purple starlings. He hated my map, despised its presence even.

He hated my questions of time. Time for him was the cast of the sun, the approach of night. So, we headed off into the shimmering heat, from the village at Wadi Rum. The landscape here, which Lawrence of Arabia sought solace to ‘clear my senses by a night in Rum, and by the ride down its dawn lit valley…’ is chiseled vanilla rock by salt, sand and wind, a masterpiece of the Gods.

Best Tips & Tools to Plan Your Trip

Occasionally a jeep would cruise past and unsettle the nerves, the occupants would wave and the Camels would sneer and snort. After a while, only the tush of Camel hooves on the sand, delicate and ancient, could be heard.

The Land of the Nabbateans

It was the land of the Nabbateans, the inhabitants of Petra and their descendants, the Bedouin tribes who spread out like the turquoise sand all over Arabia. The Greek historian Diodorus in 30BC recounted how the Nabbateans defeated enemies by hiding in the desert until the intruders, without water, were enveloped in the killing sand.

I felt a bit like that as we trod on, a Crusader fort appearing like a quivering ephemeral relic, high above a hill, long forgotten by the Bedouin, long gone.

It was a landscape that staked the permanent over the ephemeral, a desert that disliked newcomers, only the occasional lizard scattering over the stones or a skeleton baked in the sand. It was the world of the Bedouin, enclosed by sand, envied by other tribes, taxing the trade routes up from the Levant, through Petra, into Arabia.

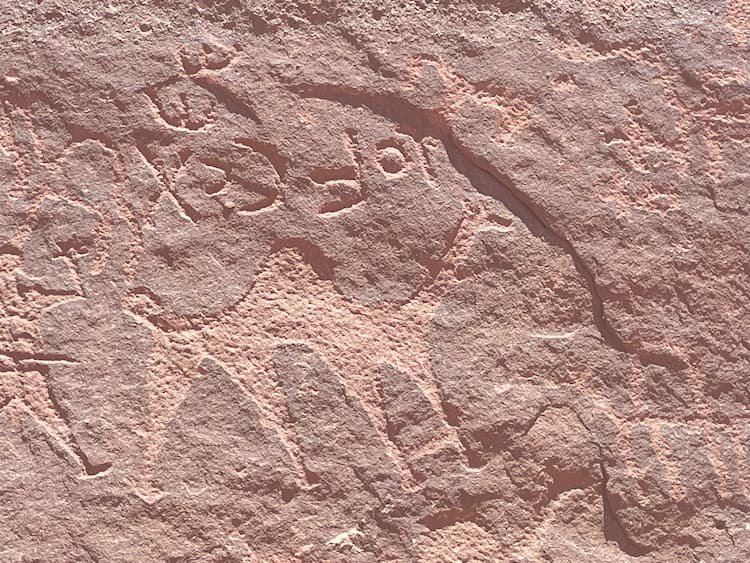

The Bedouins wear the Nietzschean mask proudly, one of aloofness, inscrutable, they show little emotion to the outsider. Hassan pointed to some Nabbatean engravings on a rock face, older than time, of figures shepherding camels. The same tribe from antiquity perhaps.

The Bedouin are closely formed tribes; at Wadi Rum a population of 3500 is one clan and they do not allow outsiders in. The sun is now like a shearing hot lance stabbing you as your face turns to the red of the sand.

We Settle In

We settle, after 3 hours out, under some shade of rocks and Hassan gathers a group of cans thrown into the sand by a tour group in a pickup. Hassan ties the camel’s legs to stop escape and we settle for lunch which he cooks under some stones and brews up the Bedouin tea.

He speaks little English while I ramble on about the Crusaders and Lawrence. He points to the Crusader fort with nonchalance, still hanging in the distance like a crown of thorns, as if it were just a passing fad, like the Crusades. Yet the Bedouin are still here and Lawrence is long gone. The desert is permanent and everything else, progress, technology, are passing by for the Bedouin.

Lawrence’s house is now a pile of stones, a peculiar outpost where some Bedouins set up an impromptu tent offering tea and Coca-Cola. Hassan hands me a pair of binoculars and points ‘Camp!’ I ask him how far and he looks at the sun and tells me ’10 minutes’.

I’m no Wilfred Thesiger and my stomach shakes like a jelly as the Camel bolders on. I can’t see anything in the distance except sand and rock but Hassan assures me that the camp is near. A Bedouin’s ten minutes can be a lifetime, however, and after 33 more hours, I show Hassan my wristwatch.

‘What is it ?’ he asks waving away my Crusader petulance. The traditional role of ‘rafiq‘ or guide was a solemn role for the Bedouin. You must have a ‘rafiq‘ to travel in tribal areas; there is no law ordaining it, except natural law and custom. Yet to be in someone’s charge is unsettling; to give over that trust to a complete stranger.

I’d read that Charles Huber, a German traveler in 1884, had been murdered by his ‘rafiqs‘ when they discovered he was a Christian. I batted away any religious questions with the assurance that I had read the Koran -‘very interesting’, which received a strange smile from Hassan.

At least he had not reached for the dagger by his side. Hopefully, that was for errant Camels, rather than errant Irishmen. For a Bedouin to turn against his charge was extremely rare, a heinous crime in the tribe, however, and if committed then the man was ostracised by the clan, a death sentence in family tribes. ‘Bowqa’ or treachery was the worst crime in the Bedouin community.

And I was assured after reading Wilfred Thesiger’s accounts that the Bedu were so respectful of the dignity of others that they would rather kill a man than torture him …

Minutes Turned Into Hours

The 10-minute journey turned into another epic. I felt like an extra from the David Lean film ‘Lawrence of Arabia’; minutes turned to hours and no camp on the horizon. Six hours out in the tortuous sun and, as I became delirious, I entered a blissful oasis of peace; only the echoes of footprints on rocks and the reggae rhythm of the camel.

When we arrived at the camp my lips looked like Mick Jagger’s. There was just a hassle of erected linen tents and a fireplace dug into the ground. The Bedouin camp dwellers were asleep in the afternoon heat. There was no internet, no phone, just a makeshift shower attached to a solar panel outfit that sat on the rock overhang like a time machine.

The shower was like hot spiky scalding Arabic coffee. The bottled water as if from the hot springs of Santorini. To go for a walk was a death sentence. Near sunset, I took a walk out plodding through the sand. I came across a skeleton that resembled a human but I assured myself it was Neanderthal and turned around.

The Bedouin cooked up a superb tagine of chicken and spices buried in the subterranean oven for hours and in the dusk, little lights zig-zagged across the sand towards us. I was expecting Luke Skywalker and R2D2 but the jeeps of new travelers swept in and soon we were swapping stories of mint tea and haggling with the Bedouins in Petra.

The Magic Started at Night

The magic of the camp started at night though as the sun fell behind the rocky hills and a thousand shadows raced across the sand like lizards. The camp was lit up in a Martian shade of red which slowly cooled and everywhere then was coal black except for the permanent stars which danced on the heavenly stage, amongst reverent hushed tones like a vigil, and demanded the limelight.

Sleeping under cool stars, the absolute cleansing silence, on the rugs like the Bedouin, I dreamt of a last outpost where civilization had regrouped; no cities, no wars, and for one night I was there in the red carpet of silence.

Inspire your next adventure with our articles below:

Author Bio: Brian Patrick Bolger studied at the LSE. He has taught political philosophy and applied linguistics in Universities across Europe. His articles have appeared in the US, the UK, Italy, Canada and Germany in magazines such as ‘Asian Affairs’, ‘Deliberatio’, ‘L’Indro Quotidiano Indipendente di Geopolitica’, ’The National Interest’, ‘GeoPolitical Monitor’, ‘Merion West’, ‘Voegelin View’, ‘The Montreal Review’, ’The European Conservative’, ‘Visegrad Insight’, The Hungarian Conservative’ ,’The Salisbury Review’, ‘The Village’, ‘New English Review’, ‘The Burkean’, ‘ ‘The Daily Globe’, ‘American Thinker’, ‘Hungarian Review’, ‘The Internationalist’, ‘Philosophy News’. His new book- ‘Nowhere Fast: Democracy and Identity in the Twenty First Century’ will be published soon by Ethics International Press

- Together at Sea: A Mediterranean Family Adventure - April 27, 2024

- Travel Guide to Colorado - April 26, 2024

- Travel Guide to Croatia - April 26, 2024