So there I was. All alone. At 2:15 am. Lost at the base of Mt. Sinai.

So there I was. All alone. At 2:15 am. Lost at the base of Mt. Sinai.

I scanned with my flashlight, desperate to find even the faintest indication of a footpath. Did three rocks in a seeming line constitute a proper boundary? I saw a slight incline with hardly any rocks. Was that the beginning of a heavily traveled trail?

How I managed to lose 50 hikers on one of the most toured mountains in the world is a feat that would impress even Moses. Sure, I can’t turn a rod into a snake and back again, but if he had my skills of navigation and evasion, Moses and the Levites would’ve shaken off the pesky Egyptians and reached the Promised Land in no time. They probably wouldn’t have had to waste precious God favors in splitting the Red Sea.

Two hours earlier, I had been crammed in the back corner of a minibus in Dahab, a budget traveler’s paradise on the Gulf of Aqaba. I first heard about the town on a Luxor-bound bus from Cairo. I sat next to a Pennsylvanian–turned–English student with chronic fatigue syndrome.

Just before dozing off, she said “Dahab isn’t like Cairo,” where she had to jog in the morning wearing sweat pants and a shirt. Cairo is a conservative place and women better cover up if they don’t want to arouse too much attention. “In Dahab, you can wear tank tops and shorts. It’s just like southern Europe,” she told me.

Dahab is laid back and cheap. Many travelers end up spending months in the town as diving courses are offered as abundantly as the fresh seafood. After snorkeling or windsurfing, visitors grab mango juice and listen to the Reggae music of Bob Marley. They eat kebabs and smoke a sheesha (Arabian smoking pipe) later that night. The name of a souvenir shop says it all: Cleopatra Rasta Shop.

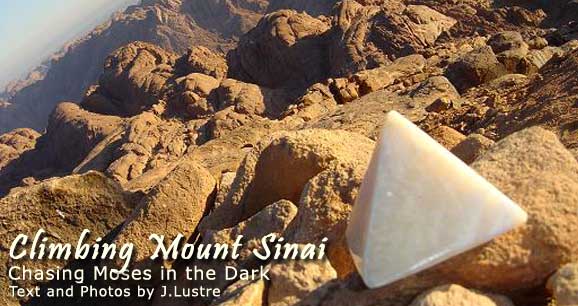

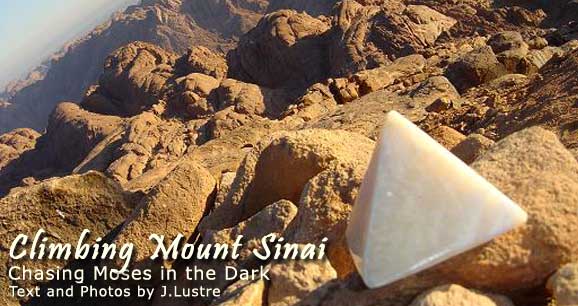

One of the few landlubber excursions is a nocturnal three-hour hike up to Mt. Sinai (7,496 feet or 2,285 meters above sea level), timed perfectly to observe the sunrise from the pinnacle.

The tour minibus included a couple of other Americans, four Slovenian guys, two Danes with convincing American accents and also a French contingent. We were assured that the clear paths would make it an easy hike. Carrying a map was optional ― there were going to be so many people there. Just follow the leader.

After a two-hour drive, we arrived at the base of the mountain, just below St. Catherine’s monastery, which was founded in 300 CE and houses what is believed to be a direct descendant of the Burning Bush. According to the Old Testament, God used the Burning Bush to speak to Moses.

As soon as I left the bus, I headed for the bathroom to put on pants and a sweater. The temperature had dropped at least 50 degrees F (10 C) from the daytime high. It was only going to get colder and windier during the climb. By the time I double-checked my gear and clothing, and put on my earphones, there were only six people left at the base.

I was not going to be the last one to the top, so I began power walking. This was the mistake. I began racing, competing with a pack of world-class hikers who burst out of the vans and sped up the mountain, leaving a flurry of dust behind them that settled by the time I crossed the same area.

They had scaled past so many turns up the mountain that I could no longer hear their stampeding or see the glow of their flashlights. Moses had a pillar of fire guiding him at night. A sympathetic firefly would have been enough for me.

I made out the shapes of two camels and three Bedouins. They were presumably headed for the main camel camp, where the animals can be hired as an alternative to hiking. The camp had to fall on the main path, I thought, so I followed. As I approached them, one of the men seemed extremely tall and was walking with an unnatural gait that somehow felt threatening, like the lanky walk of a volatile alcoholic in a parking lot, or the deceptive swaying of a martial artist fighting in the drunken style.

Naturally, I tried to get closer. I couldn’t shine my flashlight directly onto the figures, but the moonlight finally revealed that the dangerous man was actually just a malnourished camel. So I followed the threecamels and two Bedouins.

We came upon the silhouette of the monastery. I paused to orient myself according to the map I was shown in Dahab. The map was simple enough that I was able to memorize it. “There are two trails,” the man at the tourist office had explained, “both begin just past these two pillars. The one that turns to the right is the much faster, but steeper Steps of Repentance. Straight past the pillars is the easier but longer Camel Path.”

I saw the pillars, gained my bearings and also managed to lose sight of the camels and Bedouins. But I saw a faint, stationary glow in the distance. That had to be the camp.

I reached the camp by climbing over rocks and entering the wrong side. I saw dozens of resting camels as I walked gingerly around them. The animals’ legs were bent under their large bodies.

looked at me as groggy, overworked creatures would. They wondered what I wanted, wondered why I’d chosen such a silly entrance, but were too tired to help. I smiled at them, apologizing for the earlier-than-normal wake-up call. I approached the men, huddled around burning lanterns. They were wearing turbans and long, draping gowns. With gestures, I asked for the path and the men pointed.

The path was indeed well-delineated. I continued to power walk, optimistic that I would still be able to catch up with the crowd. Even though the path was clear, there is safety in numbers, and I never underestimate my ability to screw up.

Walking in the dark had one very powerful psychological advantage. I never knew how much farther. I couldn’t tell how much higher and didn’t fear coming upon a particularly steep section. Because I could see only six feet (1.8 m) ahead, the hike became a chain of manageable steps and not a protracted battle of Biblical proportions.

I stopped after a half hour to remove my sweater and to tighten my large fanny pack that had begun to slide down, hampering my stride. I found a flat rock and sat down for a few moments. The moon, while only an eighth full, was bright enough to cast my shadow. I left my flashlight turned off.

The moonlight shone through a perfectly clear sky and illuminated the rugged, arid terrain with a faint blueness. It bleached away the colors, transforming a presumably ruddy palette to a desolate monotony; the color of steel, of the moon itself. Newly visible stars formed constellations I had never seen. A group emerged to resemble a near perfect circle, like the studded collar of a massive canine or that of an even more terrifying suburban punk.

I extended my arms skyward. I formed a rectangle by connecting my thumbs and forefingers. I counted the stars within this frame, each knuckle spanning trillions of miles, eclipsing entire solar systems. Each wrinkle of my finger the size of worlds within which a similarly predisposed creature was counting the stars along with me. The universe is of unimaginable bigness and the number of habitable planets still so vast that the possibility of an alien creature mimicking my actions was, I believe, very likely.

But my interstellar communion was interrupted by a flickering army of flashlights. There they were. But they were below me, behind me. As I would later find out, all the other hikers had prepped themselves in the courtyard of a small cafe. They were obstructed from my view by a wall of minivans. I did not lose them ― I ran past them. I had been racing no one. I pointed my light at them. Dot-dash-dot dash-dot-dash dot-dash-dot.

One of the hikers reciprocated. There I was, having a Moses moment. I had been utterly convinced of my failure as a pathfinder when I suddenly found myself as a leader. My flashlight was a beacon, my stride set the pace. But I had become accustomed to the silence and the light. I didn’t want a cacophony of footsteps and foreign accents messing the whole thing up. I turned off my light and walked away. Unlike Moses, I left my people behind.

An hour and a half later, I was at the final 350 steps. A Bedouin merchant said it was too early, nobody was up there yet, and that I should buy some of his overpriced chips and tea. Halfway up, it seemed the Bedouin had a point. I refused to rest throughout the entire way, and my body began to shake. Moses had a walking stick.

My trembling knees were begging for one. But I reminded myself that if an 80-year-old man with slippery sandals walked up this mountain and came down carrying two stone tablets, I had nothing to complain about. I was carrying a camera, some chocolate-chip cookies and two juice boxes. It was hardly a load to warrant divine intervention. So I just kept walking.

I was not the first to the top. Three guys had taken the Steps of Repentance. Three others had camped out from the previous day. Another merchant approached me, offering to lend me his blanket for US$ 1.50. I asked him where the sun was going to rise. I situated myself near the edge, wrapped myself in the blanket, took out one of the juice boxes and waited.

During the next 90 minutes, people began piling into the area. Some were quick to sleep. Others began to eat. Some stargazed.

It began sometime after 5 a.m. It’s hard to give an exact minute to an event that is part of a seamless process. A thin white thread of a satellite appeared over the horizon, in competing luminescence with the bright fingernail clipping of the moon. The light was elegant, demure in the company of stars and the faint dusting of the Milky Way galaxy. Somewhere east ― was it Saudi Arabia? India? How far could we see? ― the white thread quickly unraveled, expanding in a spectrum that leaked orange over the landscape, over everything.

And then a fierce orange disc rose and set the lunar desolation, the silent eloquence of blues on fire. In its unyielding march westward, the disc claimed territories under this orange glow, increasing its dominion with every passing moment. In time, those of us on the mountain also submitted to its presence and somewhere in Morocco or Spain, it was still dark and quiet.

“The smoke billowed up from it like smoke from a furnace, the whole mountain trembled….” ― Exodus 19:18

We witnessed the vast, beautiful dance between night and day, a process that determines our concept of time but is timeless itself, which gives rhythm to seen and unseen occurrences that repeat over days, years, eons and which is undoubtedly linked to cosmic forces beyond Hubble’s scope, beyond astrophysical explanation, beyond even the most informed imagination.

This process is hinged upon systems in a god-sized mobile, teetering and swaying in delicate balance, measured no longer by human numbers but with words invented to capture the unfathomable: for-ever, every-thing. Things as massive as planets and as small as rocks and sleepy, hungry people on a mountain top. This is what it feels like to feel the Earth move, to identify one’s self as a microscopic ― but no less integral ― participant of the dance.

If You Go

There are daily buses from Cairo to Dahab. Make sure to buy your ticket a few hours before departure, as seats can fill up quickly. It is an 8-9 hour drive to Dahab. Expeditions to Mt. Sinai are nightly and are organized by many agencies in Dahab.

Egypt Ministry of Tourism

www.egypttourism.org

Sinai Homepage

www.geographia.com/egypt/sinai