Perhaps it was the aftermath of four weeks in India spent negotiating my every movement that had considerably shortened my fuse. Perhaps my cool Canadian good nature had melted away in the three-digit steamy heat. Or perhaps, like the Grinch, my heart was simply two sizes too small that day.

I was cranky, unreasonably chagrined at paying 30 Sri Lankan rupees for a second-class train seat, only to discover all seats taken when I boarded, fully 45 minutes before departure. The one-hour train ride from Kandy, a city of central Sri Lanka to Rambukanna, and another half hour by bus to the Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage was far too long for me to stand, especially at the unreasonable hour of 7 a.m.

I had paid for a seat. I plopped down on a third-class bench and angled out of the window until I caught the eye of an agreeable Sri Lankan rail worker. He inspected my ticket, listened earnestly to my predicament, and cheerily beckoned me back to the second-class car: “Come, come!”

It was early; I was fatigued, sweltering and peevish. For all its magnificent splendors, there is no sufficient cappuccino equivalent in Kandy, and I was wrathfully into a week of full-blown caffeine withdrawal. I was not naively going back to a carriage I knew was full. It could be a scam:

I might not only lose my third-class seat and have to stand for a whole hour, but possibly have to pay for another pass. (In my defense, this actually happened to me in China.) I snatched my ticket back with a petulant exhalation, slumped against the open window and sulked into the tropical scenery, determined to commandeer as much space as possible along the cracked blue vinyl.

The jungle canopy was luxuriant in the bright face of morning. The verdant tangle swayed in a sweet zephyr while fruit burst from the earth in all manner of seeds, flowers and spikes. Waterfalls streamed over smooth-shouldered chocolate boulders, easing into pools mirroring sapphire sky and raw-silk clouds. Inside, locals unconcernedly alternated between sitting and standing.

Adults and children sang together, white teeth glinting delightedly in the splintered light, in a pleasured crescendo as the train shot through short black tunnels. The passengers around me eagerly consumed exotic snacks: baskets of crunchy fried bundles laced with spicy dried peppers; mammoth cobs of steamed golden corn; bunches of enigmatic sugary fruit. Grudgingly, I felt my irritations begin to subside.

Several passengers pointed out the Rambukanna station to me. I stalked to the main road, past the sinewy barrier of auto rickshaw drivers and friendly touts. Where was the connecting bus to the village of Pinnawala? After I asked two different people and received convincing gestures in completely opposite directions, my anxiety ratcheted up a few notches.

Hungry for business and undoubtedly smelling sweaty desperation and foreign currency emanating from my incandescent white skin, a line of auto rickshaw drivers commenced vigorous animation of their green and yellow tin chariots.

“Can I help you?” I looked skeptically from the gritty ground at my dirty feet to see pressed trousers, a casual pinstripe shirt and a welcoming smile.

I realized that as independent as I wanted to be, I did, in fact, need some help. Through clenched teeth, I ungraciously replied that I needed to find the Pinnawala bus, but that I did not want to have to pay him to show me where it was.

The warm smile wavered somewhat, like a cloud passing through a clear afternoon. “I am not a beggar! I don’t want your money. I am a real Sri Lankan! I will help you — come!” And my day-long lesson in humility began.

The self-assured fellow walked me to the bus, secured me a window seat, and waited on the bus until the driver confirmed that it was, indeed, headed for the elephant orphanage. Twenty minutes later, no fewer than five passengers and the driver cheerfully pointed out my stop.

Sri Lanka, an island country in the Indian Ocean just southeast of India, is home to about 3,000 wild elephants, down from about 20,000 animals 150 years ago. Humans encroach on their habitat, which is rapidly shrinking.

When elephant cows are killed, if the hungry animals raid a farmer’s field for example, the nursing young usually have no other chance of survival than the 24-acre (9.7 hectares) Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage established in 1975 by the Sri Lanka Wildlife Department. Today, the orphanage is also a breeding ground for elephants.

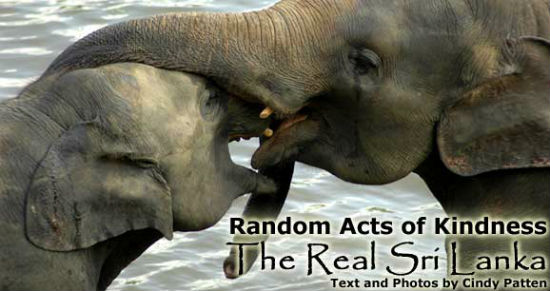

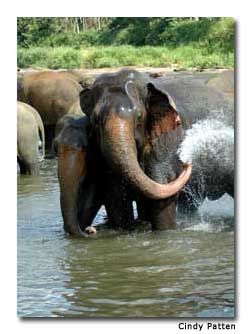

I spent a wonderfully quiescent afternoon at the orphanage, exceeding all my elephant expectations. The enormous prune-skinned mammals appeared genuinely sanguine, and their mahouts treated them with care. The pinnacle was bath time in a nearby river, where each day the 80 or so parched pachyderms spend hours frolicking.

Grinning mischievously from tusk to tusk and winking long-lashed, jovial eyes in the cool spray, they become surprisingly playful, wrestling and slapping at one another like a gaggle of junior-high-school students on a loosely supervised field trip.

Occasionally, small posses sneaked to the far bank for a vigorous dust bath, or trotted downstream into dense bush to foray for a leafy treat. Several reclined in the river, snorkeling in bubbly gusts from their brawny, expressive trunks.

Wandering back toward the main road, I paused to admire some souvenirs. I bargained heartily for several treasures before finding my way to the bus stop, weighted under a backpack, a colossal camera, and now two souvenir tables and a set of cinnamon-bark plates.

Sarath, the congenial store clerk, was waiting for the same bus. I found myself whining about continually having to be on my guard as a traveler and how tiresome I had found the morning’s train experience. Sarath spoke compassionately. “That’s how it is with Sri Lankans also, we do not always get a seat, but there was room for you to stand, wasn’t there?” Oh.

When the medieval bus ground to a tortured halt, Sarath helped me wedge into the standing-room-only vehicle. Before we lurched two blocks, a teenager smilingly nodded to me and surrendered his seat. Sarath grinned at me warmly: “Because you are a foreigner!” I felt a strange little tap on my heart, recognizing just how unselfish and truly loving the small gesture was.

Bus fare clenched in my fist, I waited for the conductor to collect. It never happened, and I suspected that Sarath had paid for me. When I tried to reimburse him, he chuckled merrily and waved my money aside, ushering me onto the connecting bus. Another tap stroked my heartstrings.

Again with standing-room only, we had hardly proceeded three minutes before a young schoolgirl in a white blouse and blue jumper sunnily volunteered her seat to me and all my formidable packages.Tap.

The bus clung to the road by virtue of gravity, the singular saving grace of a prodigious passenger load. Knotted into a mass of standees, the girl pitched defenselessly like seaweed in a tidal rip while I reposed conveniently. Tap. The elderly gentleman sitting beside me held her heavy backpack so that she could better grip the overhead rails. Tap. Tap.

He then sincerely apologized to me for his country’s political tensions, mostly between the government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, who seek independence in the northeast corner of the island. It was not real Sri Lankans who were at war, he remonstrated. Real Sri Lankans are peaceful, and revile the bloody battle that has internationally defined their small nation since 1983. He was very sorry for me, and hoped I would return to experience the good side of his country in the future. Tap. Tap. Tap.

En route to Kandy, my conscience gnawed at my ego to exorcise the tawdry fiend that had earlier possessed my sensibilities.

I hated to admit that hyperactive conjecture had triggered my early morning wash of negativity. The difference between second- and third-class train tickets — regardless of whether or not one arrived early enough to secure a seat — was 6 Sri Lanka rupees for locals and foreigners alike. I had allowed the equivalent of less than six cents U.S. induce me into a state of Western infantilism.

I have a new goal: to one day possess the spontaneous charity and character of a real Sri Lankan, and to touch the hearts of others with such caring, selfless acts of respect and kindness.

If You Go

Sri Lanka Tourist Board

www.srilankatourism.org

Elephants in Sri Lanka

www.elephantsinneed.org

- Life of a Champion: Exploring the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville - April 19, 2024

- What It’s Like to Live as an Expat: Lake Chapala, Mexico - April 18, 2024

- Top 5 Spots for Stargazing in North Carolina - April 17, 2024