I met John in the lobby of the El Ati hotel in Erfoud, Morocco’s tourist-desert city. The Englishman who called himself a modern troubadour had just made a trip through the Dades Valley and Canyon where countless historic mud fortresses called kasbahs dot the landscape. When I asked what he thought of these trademarks of Morocco, he answered in poetry:

I met John in the lobby of the El Ati hotel in Erfoud, Morocco’s tourist-desert city. The Englishman who called himself a modern troubadour had just made a trip through the Dades Valley and Canyon where countless historic mud fortresses called kasbahs dot the landscape. When I asked what he thought of these trademarks of Morocco, he answered in poetry:

Kasbahs, melting under torrential rain,

Kasbahs repaired to rise and live again,

Kasbahs sprouting new, small and grand,

Fairytale forts, built by magical hands.

The next morning our group of five followed in John’s footsteps as we made our way westward from Erfoud to explore kasbah land ourselves.

Morocco was a French protectorate from 1912 and achieved independence in 1956. The full Arabic name of this Kingdom in northwestern Africa is Al-Maghreb (“The West”) and widely used in Arabic. Morocco, as the country is called in most other languages, derives from the name of the former capital, Marrakech.

It is believed that the Arab tribes, which came from Yemen, brought with them the art of building kasbahs (from Arabic qasbah for “citadel”) because the same type of fortress-castle is still being constructed there.

In the oases land of southern Morocco, this form of building took a firm hold. Built from the soil of the countryside, which is mixed with straw, kasbahs cost very little — ideal for people who have hardly any money to spare. They fuse traditional Berber battlement exterior building techniques with finely decorated interiors inspired by the Andalusian palaces of Moorish Spain.

Men of modest means construct their small homes kasbah-style, while the powerful and affluent erect huge fortress structures as a sign of wealth, which are considered the true kasbahs.

After a leisurely three-hour drive through a sparsely settled, semi-desert land we reached Tinerhir — a rich agriculture town of 10,000, some one hundred miles (160 km) west of Erfoud. Set in a fertile valley amidst some of the most beautiful landscape in Morocco, it is the door to the Todra Gorges, Morocco’s most famous natural wonder.

As we drove northward, our driver first stopped atop a cliff to let us enjoy the splendid view of the green valley below. Thousands of fruit trees dominated by countless palms were intermixed with fields of grain. A galaxy of gold-colored kasbahs, a good number newly built, contrasting with the silver-green of the olive trees, the deep green of the date palms and the emerald green of carpet-like grain fields, made it an unforgettable sight.

A short distance onward, we reached the Todra Gorges — probably the most impressive geological formation in Northern Africa. Two steep limestone cliffs rise vertically through gray, green, yellow and red rock to 984 feet (300 m), towering above the gravel base of the canyon, which is at its narrowest point only 33 feet (10 m) wide. A small crystal-clear stream runs through it, reputed for curing sterility in women.

We spent an hour examining the gorge, then returned to Tinerhir to relish this oasis town nestled in a surrounding of olives, pomegranates, date palms and a large number of Kasbahs. Here, we also found the ruins of one of T’hami El Glaoui’s mud castles. El Glaoui was a Berber chief, a French-supported warlord and pasha from Marrakech who controlled large parts of southern Morocco from 1912-1955.

Westward from Tinerhir, we drove for half an hour through a barren landscape until we reached Boumalane — noted for its fantastic-looking Hotel el-Madayeq, built kasbah-style of course, and overlooking the town. After examining this superb structure, we took the road which led to the Dades Canyon, an awesome and torturous limestone gorge with dizzying cliffs, dotted with bizarre rock formations resembling melted wax. It was a rough, jagged universe, a mixture of mauve, purple, red and other colors.

Carved by the Dades River thousands of years ago in eerie, but breathtaking shapes of eroded limestone, the canyon is lined with innumerable kasbahs built by chieftains in the past ages. These mud fortresses of the strong seemed to be everywhere. Their adobe walls and squat towers are fine examples of Arab-influenced Berber art, whose motifs are seen on the local carpets, jewelry and pottery.

As we looked down from our twisting road to the valley below, it seemed that the grass was greener, the soil redder and the kasbahs more appealing than those outside the valley. The fantastic colors of the stone cliffs contrasting with the valley green and towering kasbahs had us enthralled and gave us a feeling that we were in a fairyland of enchantment.

Back from Boumalane we drove westward, following the Dades valley — a thin line of green in a barren world, called the “Valley of a Thousand Kasbahs.” Between Boumalane and Kelaa M’Gouna, our next stop, the road was lined on both sides with Kasbah-style buildings — many newly constructed. Until we reached Kelaa M’Gouna, the whole route appeared to be one continuous town.

Kelaa, 6,560 feet (2000 m) above sea level and called the “Rose Garden” of the Dades Valley, is a magnificent and superb place, and the center of a fertile rose-growing oasis. The French introduced the Damascus rose from Syria in the 1920s into the valley where it thrived. In spring the fragrance of these flowers intermingled with those of the fruit and nut trees make it an enchanted region.

Travelers have written that in May and June, at the time of the Rose Festival, the countryside around Kelaa is completely covered with roses whose aroma hangs heavily over the countryside and the town itself. Perfumes from the fruit orchards, almond trees, and grape fields smothered by rose hedges produce a feeling of heavenly seduction.

For a short distance west from Kelaa, the highway was edged on both sides by greenery and imposing kasbahs and more new kasbah-like homes, but soon we were driving in an arid landscape until we reached Skoura, a luxurious oasis also famous for roses, which grow amid grain fields and palm trees.

West from Skoura, we drove through countryside full of dry river-beds, under the shadows of the snow-capped High Atlas mountains looming in the distance, until we reached Ouarzazate, built by the French as a garrison town in the heart of Morocco’s Great South. Located at the crossroads of the Draa, Dades and Sous Valleys, the town is encircled by a barren landscape and overshadowed by the snow-capped Atlas.

A provincial capital of about 50,000 inhabitants, whose setting is romantically scenic, it is an important pre-Saharan crossroad — an ideal point from which to set out on journeys of discovery to the valleys of the kasbahs both to the south and east. Even though it offers all the amenities of a modern and vibrant city, its atmosphere is tranquil and fresh. Nicknamed the “Pearl of the Sands,” Ouarzazate appears to have a bright tourist future.

Here, we spent two days exploring the many kasbahs in town and on its outskirts. The most prominent were Tifiltout, parts of which have been renovated and Taourirt, both built by El Glaoui. The latter is considered to be the mother of all kasbahs. Encompassing a series of crenellated towers, rising out of a mass of closely packed houses and lavishly decorated with geometric motifs, it is one of the most beautiful in Morocco.

At one time, it was on the edge of the city, but today the modern town is surrounding this popular tourist site, where the movie “The Jewel of the Nile” (1985) with Kathleen Turner and Michael Douglas was filmed.

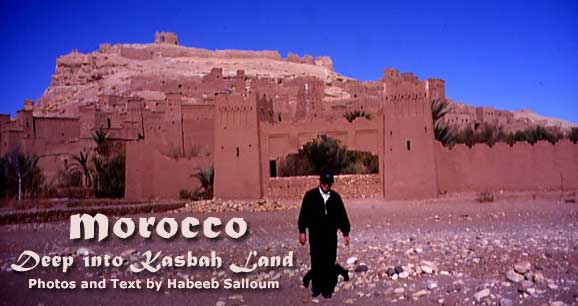

Leaving Ouarzazate, we stopped at the Atlas Cinema Studio where a great number of films are shot, then continued to the largely uninhabited strengthened village of Aït Benhaddou. From a distance, its adobe buildings and ancient homes looked magnificent. But only a small section of this model of architecture has been restored by UNESCO who recently declared Aït Benhaddou a World Heritage Site.

Just eight families now live within its walls, whereas a few decades ago there were hundreds. The village is on the itinerary of tourists thanks to Hollywood. Movies like “Gladiator,” “ Sodom and Gomorrah,” “Jesus of Nazareth,” “Lawrence of Arabia” and “The Jewel of the Nile” were filmed in one of these enchanting ksours or castles that no visitor to Morocco should miss.

If You Go

Most visitors don’t need visas to enter Morocco — only valid passports.

If you know French, which is widely spoken in Morocco, it’s easy to get around in Morocco. But many locals also speak some English.

Morocco ’s currency is the dirham (MAD). US$ 1 equals MAD 8.4. You can exchange money at banks or hotels. The rates are all the same with no commission.

When traveling in Morocco, trains are the most comfortable. Buses are inexpensive – CTM the best. Small autos, with unlimited mileage and fully insured, rent for about US$ 60 a day insurance included.

Tips are expected for every service — always carry small change.

Barter for all tourist items and never shop with a guide. His commission is usually about 30 percent.

At night, avoid dark alleyways. Morocco is safer than many other countries, but muggers still stalk the lonely streets.

Moroccan Tourist Office

www.tourism-in-morocco.com

- Exploring the Culture and History in Fascinating Astana, Kazakhstan - July 24, 2024

- Breakers & Beyond: Top 10 Things To Do in Newport, Rhode Island - July 23, 2024

- Laid-Back Lombok: Coconut, Coffee and Coral Reefs - July 22, 2024

I recently visited Merzouga and it was an absolutely incredible experience. The beauty of the Erg Chebbi dunes took my breath away, especially during the camel trek at sunset. Spending a night in a traditional desert camp was a highlight, with warm hospitality, delicious food, and stunning starlit skies. Interacting with the friendly locals and exploring nearby villages added a cultural touch to my journey. The guides and drivers were knowledgeable and passionate, enhancing the overall experience. Merzouga is a transformative destination that combines breathtaking landscapes, cultural immersion, and a sense of tranquility. I highly recommend it to anyone seeking a remarkable adventure.

Really comprehensive, well-laid out options and descriptions of each. Much appreciated!

Wow, beautiful article! Thank you for sharing.