The first leg of our Trans-Siberian railway trip on the Rossiya (Russia) train took us from the gloomy port of Vladivostok to Irkutsk near the shore of Lake Baikal. While some brave souls take the Rossiya for the full seven days to Moscow without a breather, we decided to break it up with a stop in Siberia after the third day.

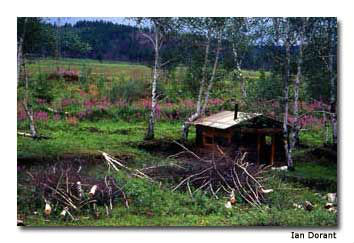

For three days and three nights, we passed through taiga forests, Siberian flood plains and rolling hills covered with purple and pink wildflowers. With the tracks following an inland route parallel to the borders of China and Mongolia, we saw the landscape change several times a day, with a favorite being the low green hills that we learned usually preceded a village of ramshackle wooden cottages and subsistence farms. But we soon found out that a Trans-Siberian story isn’t really in what’s outside the window — it’s more about who is inside looking out.

One Thursday morning at 10:35 a.m., my boyfriend Ian and I were sitting on the bottom two bunks of our standard second-class cabin, 5,772 miles (9,289 km) from Moscow. As the triumphal departure music blared, we waited nervously to meet our travelling companions, who had left their luggage on the top bunks and joined the chaos of people in the aisle, chatting and waving to family and friends out the window. A man with thinning grey hair just visible beneath a plain blue cap cheerfully sat down and launched a barrage of Russian at us. Our polite smiles and nods encouraged more friendly Russian chat, which sounded suspiciously like a question.

“I’m sorry. We only speak a little Russian. Do you speak English?” Ian asked him hopefully.

The man, who we soon found out was nicknamed Vladimir, sank back, deflated. “School,” he said.

“Oh, you learnt English at school?” I prompted.

He gave a half-smile, stood up and busied himself with his luggage. “Yes,” he said, his last word for 23 hours. He climbed up onto the bunk and fell asleep.

As the train shuffled out of the urban landscape and into surprisingly endless greenery, our fourth cabin occupant appeared. It seemed a pity that Vladimir had already retired for the day, because her English was more than sufficient to have helped us make proper introductions.

Tanya was a 50-something woman from Vladivostok and she shared her homemade jam with us, on bread bought from the vendors crowding the tracks at the station. Eager to practice the English she’d studied at university, she regaled us with reminiscences of Soviet times, the effects of the economic restructuring of perestroika and the subsequent fall of Communism, and her concerns for the future.

“Before perestroika, if I wanted a particular thing, coat, or shoes, or furniture, I had to ask around to people I know, and wait for a favor,” Tanya explained. “But now, no waiting. If I have enough rubles, I can get whatever I want.” I thought of the tiny outdated selection sitting forlorn in the GUM department store in Vladivostok and knew sadly, this wasn’t exactly true.

She paused as the carriage provodnitsa (train attendant) entered our cabin, wanting to check our tickets and collect money for bedding. While Ian argued that we’d brought our own sleeping sheets and didn’t need to pay for extras, I ran my brain through all I’d learned in high school history classes about life behind the Iron Curtain. Tanya continued before I’d formed my next question.

“Before perestroika,” she said, “everybody knew their place in life. They could make plans. We had only a little money, but it was reliable. Now, everything is always changing. Banks close and we lose our money. Even the American dollars we all keep in a cosy place are not safe. The value goes down. Nobody can plan anything.”

She was the first Russian, but not the last, to speak to us so plainly about their situation. “It’s hard for us to imagine a life like that,” I said.

“In Russia,” Tanya said, “we have a saying.” She paused for a moment, tapping some excess jam off her knife. “Maybe in English it says, ‘Life is very good, except where we are.’ I think it’s true.”

“Which do you prefer then, life under socialism or now?” Ian tentatively asked.

Tanya didn’t need time to think. “I don’t choose which is better, I just say, I like a normal life.”

That evening when the train reached its ninth stop of the day, Vyazemskaya, near the far northwestern tip of China, we shook hands with Tanya and watched our best-ever history lesson walk off the train to meet her sister.

On Friday morning, Vladimir finally reappeared. A 15-minute stop at Belogorsk, still almost 4,900 miles (7,866 km according to the regular markers) from Moscow, refuelled both in energy and confidence, and from a long string of syllables we heard something like “Australia.” We seized on this and within seconds had drawn a map of our country and labelled some of its famous cities.

“Ah…Canberra?” Vladimir asked.

“Yes, here!” I said, marking a big cross to show our capital. Some reasoning connected to his grandfather and the navy had helped Vladimir recall the name Canberra, a puzzling memory as a ship could never reach landlocked Canberra. Just the same, it was enough to ignite a conversation. At great effort all round, we managed to speculate that Vladimir worked for the army in Irkutsk, and that his only child was a 17- year-old son at military university in Moscow. Our mutual knowledge of English and Russian exhausted, Vladimir retired again to his bunk.

Our second day and night on the Rossiya followed the routine of the first. Tranquil hours staring out the window of our cabin at the ever- changing scenery were interrupted by stints standing in the corridor gazing out the other side of the train.

We made frequent treks to the samovar (an urn with a spigot at its base) for boiling water, both to cool in our canteens for drinking later and to pour on our instant noodle dinners. As the light fell outside, Ian and I played noisy games of cards until one of us lost too often to be interested; we read Dostoyevsky and wrote long entries in our diaries. Vladimir remained with closed eyelids on his top bunk. At the most inconvenient moments, the provodnitsa would insist that we raise our feet so she could vacuum the inside of our cabin. When the darkness really fell around ten o’clock, we crawled into our sleeping sheets and were rocked to sleep by the now familiar train rhythm.

By the third morning, the 8-year-olds we’d been exchanging smiles with in the corridor finally had the courage to talk to us. Tiny Pavel, the shyest looking of the lot, ran up and down the train, asking us questions in his polite English, then returning to his mother’s carriage to learn the next one.

“My name is Pavel. What’s your name?” he began, proceeding through, “I’m 8. How old are you?” to “My mother is a doctor. What’s your job?” Pavel later introduced his three friends — all from families travelling back to Moscow after their seaside holidays — and they crowded onto one of our bunks, playing bungling bilingual versions of cards, chess and checkers. Our phrasebook got its most strenuous workout as we tried to keep up with the boys’ curiosity and to learn about their lives, too.

About 72 hours had passed when we pulled into Slyudyanka on the southern tip of Lake Baikal, a pause causing great excitement among everyone on the train except us. Being non-locals, we didn’t appreciate the quality of the Lake Baikal smoked herring offered for sale at this stop. Thanks to Vladimir’s purchases, however, we got a good chance to appreciate the not-so-pleasant odor. For that reason it was with some relief that we were able to disembark for our welcome stopover in Irkutsk. Yet watching the Rossiya pull away, taking some of our new friends on the seven-days-straight journey to Moscow, I felt almost reluctant to be on stable land, and kept imagining the chi-chunking sensation of the train as we pulled on our backpacks and walked out of the station.

If You Go

Getting a visa to enter Russia is still a little complicated — you need an invitation letter — so totally independent travel isn’t so easy. Travel agencies will organize anything from just the invitation letter and visa (usually requiring you book at least some of your accommodations) to arrangements for your whole stay or even a fully escorted tour. Homestaying is an increasingly popular (and relatively inexpensive) way to experience the “real” Russia. Hosts are often middleaged Russian widows looking for some extra income or Russian families interested in making contact with foreigners.

Tickets for trains along the Trans-Siberian route vary considerably in price according to the stops you make and where you buy them; you can travel in first class (a two-berth cabin), or for half the price, second class (a four-berth cabin). Facilities such as showers vary between trains; check before buying tickets if you need some comforts.

Restaurant cars are available on nearly all trains, but you can also stock up on food from the numerous locals plying their wares at each platform along the route. Spending several days, or even a whole week on a train isn’t for everyone, but as a relaxing way to experience Russia from end to end, it can’t be beat.

Russian National Tourist Office

Geographia

www.interknowledge.com/russia

The Man in Seat Sixty-One

www.seat61.com/Trans-Siberian.htm

- Life of a Champion: Exploring the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville - April 19, 2024

- What It’s Like to Live as an Expat: Lake Chapala, Mexico - April 18, 2024

- Top 5 Spots for Stargazing in North Carolina - April 17, 2024