We are reader-supported and may earn a commission on purchases made through links in this article.

“Lourdes? But it’s for religious fanatics! They’ve got the tackiest stuff there. I’ve heard of the holy-water bottles shaped like the Virgin Mary and hologram postcards and … ”

Lourdes, a town in southwestern France at the foot of the Pyrenees, is noted for its Roman Catholic shrine marking the site where the Virgin Mary is said to have appeared repeatedly to Saint Bernadette in 1858. For my upcoming trip, I was sent off with snickers and sarcasm.

Few places arouse as much reaction (and derision) as Lourdes does. Many of these reports revolve around the endless souvenir kitsch, the fervent religious devotion and dubious claims of miracle cures. I couldn’t wait to see the spectacle for myself.

With a population of about 17,000, this small town receives 5 million pilgrims per year drawn by their faith in the healing powers attributed to the waters of the shrine. More than half of the visitors are made up of the sick and elderly.

The American Heritage Dictionary defines pilgrimage as “a journey to a sacred place or shrine,” with a pilgrim as “one who embarks on a quest for something conceived of as sacred.” The abstract definitions meant little to me. But perhaps even jaded travelers could uncover inspiration in Lourdes, the most beaten of paths.

Along Boulevard de la Grotte, one of the main streets in Lourdes, endless paraphernalia seduced from wall-to-wall souvenir shops. I came across a black-and-white photo of 14-year-old Bernadette Soubirous, whose visions brought the city its recognition.

Though a round-faced brunette with thick eyebrows in life, she was widely depicted as a fair-haired child with a lamb. A marketing department somewhere had turned her into a poster pinup for God.

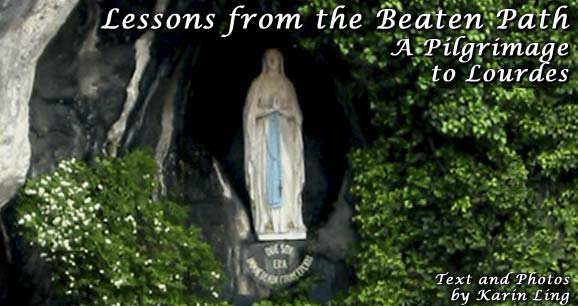

Even though I had been warned that it was “just a dent in the hills,” the Grotto of Massabielle, where the Virgin is said to have appeared, was anticlimactic. From behind the sea of people, I caught a glimpse of the Virgin Mary statue and objects hanging from the ceiling and walls of the grotto.

On the other hand, the nearby spring known for miracle-cure capabilities was an impressive gusher. A very efficient system of faucets sprouted from a curved metal railing on the side of a hill. When pushed, the timed taps released energetic streams of water. It all seemed much more suited to a campsite or a sports stadium than as the source of a holy spring.

Families lined up at the taps with 5-gallon (19 liter) jugs. A woman rubbed her feet with determination under an endless stream of holy water, and young people refilled their Evian water bottles. Everyone had a different method of stocking up on holiness.

The visual centerpiece of the sanctuaries was the Basilica of the Rosary, built 13 years after the apparitions. The breathtaking affair of spires and towers with gold detailing gave the place a surreal, fairy-tale air.

“What? Is this Disneyland?” was Benoit Porte’s reaction during his first visit. Benoit was an old college friend (we were both exchange students in England) who I remembered as having a perpetual grin on his face and a pint of beer in his hand.

He was also the only person I knew who devoted two weeks every summer to a religious organization, l’Hospitalité Saint Roch, which attends to the old and sick on their Lourdes pilgrimage.

Only in his 20s, Benoit was one of the younger volunteers. His initial judgment of Lourdes had faded as he took on his duties: changing beds, washing sheets and cleansing pilgrims too weak to do the job themselves.

Having taken part in his share of processions, prayers and masses, Benoit has come to see all of these activities as different forms of meditation. “Each person has his own way of reaffirming his faith,” he explained.

I couldn’t understand why the devoted who were ill would make a risky trip when the chance of a miracle cure was reputed to be nonexistent. I pounced on Benoit. “Don’t they get disappointed? Aren’t their expectations crushed?”

What was nonexistent was my concept of faith, so he tried to not lay too much religion on me. “They don’t come expecting miracles. Some of the bedridden pilgrims don’t see more than a handful of people all year. When they come to Lourdes, they get a rush of compassion and openness. They find themselves surrounded by people who share the same understanding.”

From a mezzanine on the side of the basilica, I paused to watch the pilgrims assembling for mass. The gentle shuffling into place recalled none of the pushing and shoving that characterized the French gatherings I had known.

Wheelchair pilgrims took up the first rows, and stretchers were assembled in front of them. For the first time since my arrival, my sarcasm faltered. “In Lourdes, they find relief in their suffering. And they give relief to others” was how Benoit put it.

Trying to reconcile my conflicting impressions of the town, I brought up the kitsch question. “Aren’t people offended that religion has gotten commercialized? Those souvenirs are so tacky.”

Without denying it, he recounted a story of a town in Argentina. To this day, the townspeople pray to a statue of the Virgin Mary that pilgrims had brought back from Lourdes. This gift was the pilgrims’ way of sharing the experience with those who couldn’t make their own pilgrimage.

One morning, I watched a man with a cane carefully picking over a selection of Saint Bernadette handbags and baseball caps. I wondered Is Lourdes just another city whose existence is centered on a thriving tourist industry? While it embraces all the requisites of such a place, it does so with a twist.

Though Lourdes holds the record for the greatest number of hotels in France outside of Paris, most are of the modest, bare-bones variety. Effort is made to provide handicap facilities, but it’s nothing else to write home about.

Nondescript restaurants offer simple French fare … plus pizza, plus ice cream, with fries on the side. Translations in five languages give their laminated menus an unexpected cosmopolitan touch.

Walking back up Boulevard de la Grotte, I paused before a series of wall hangings with prayers in 12 languages — from Maltese to Croatian to Tamil; pilgrims to this place come from distant places.

Somehow, the concept of “the beaten path” started to lose its previously straightforward connotations. In a world where there are fewer barriers to where we can go and how we can travel, our expectations are as elevated as the possibilities.

The idea of a journey as sacred means the chance to put down the guidebook checklists and skepticism. It means strapping on a little faith. When I asked Benoit why he made the trip to Lourdes year after year, he replied, “de partir ailleurs et revenir différent” — to go away and return a different person. If that is what traveling can be, then it’s a beaten path worth exploring.

If You Go

Lourdes is a 5½-hour trip by train from Paris. There are four return journeys every day.

Notre-Dame de Lourdes Sanctuaries

www.lourdes-france.org

Lourdes Tourist Office

www.lourdes-infotourisme.com

French Tourism Office

www.franceguide.com

French National Railway System

www.sncf.com

Inspire your next adventure with our articles below: