Go World Travel is reader-supported and may earn a commission from purchases made through links in this piece.

The old gentleman in pressed khakis and a blue chambray shirt stood outside the Clifden Bookshop, greeting passersby with a tip of his cap. It was a mellow 65 degrees that July afternoon in western Ireland with the sweet scent of honeysuckle drifting in the wind. As my family and I drew closer, a pair of bicyclists asked the man how to get to Clifden Castle.

“Ah, indeed, you’ll need to take Sky Road,” he said, pointing his walking stick like a compass needle. “From there, you’ll come to a stone arch leading to the castle ruins.”

Savor the “Savage Beauty”

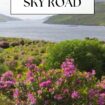

Sky Road. A circular ten-mile drive outside of Clifden, I had read, with stunning views of Connemara stretching west of Galway City, from Oughterard all the way to the Atlantic. We were in the heart of Connemara now. An area of “savage beauty,” Oscar Wilde wrote, perhaps noting its barren rockscape, deep-blue lakes, and ever-changing light.

“We’re only here for a couple more hours,” I said to the gentleman, explaining that my husband, two pre-teens and I were due 2 ½ hours east in Limerick by nightfall.

“Is Sky Road a place you’d recommend?”

“Aye, good lady, don’t miss Sky Road.” He leaned towards me on his stick, and with a knowing smile whispered, “It’ll stay with you forever.”

I glanced over his shoulder at Twelve Bens’ peaks on the horizon. Divinely sculpted angles and crowns lifted me above harried thoughts of carpools, after-school soccer and orthodontal appointments in New York. Sky Road was an opportunity to fall off the map without a plan. I imagined fields of yellow-petalled silverweed accenting a coastline of coves, islands and bogland.

A Place to Feel at Home

For as long as I can remember, I’ve felt a strong affinity with the Emerald Isle. Family and friends have often asked why. After all, DNA tests show that I’m only 3% Irish, with a predominance of Scottish and German ancestry and a touch of Swedish.

Maybe it was due to my maternal grandfather, who introduced me to the work of Seamus Heaney, whose passion for the Irish landscape lived in his poetry. My grandfather was also a master storyteller who often gathered family around the fireplace to spin tales.

His gift to enthrall us with wit, charm and verve was, in my youthful perception, Irish in nature. I grew up reading everything I could get my hands on about Irish history, culture and the arts.

Consequently, that July, when my young family and I ferried from Wales to Rosslare, Ireland, I felt a deepening kinship with the land and its people. A place where I continue to feel most at home.

We piled into our rented PT Cruiser. I drove, guided by the twisty rhythm of the road. Pinkish-orange light dazzled the horizon as we reached Sky Road. The swirl of colors set my joy in motion, as I looped around lakes, peat bogs, purple heather and a rocky shoreline, the pull of the ocean just beyond.

A Lawless Wilderness

Distant ragged peaks echoed the calls of peregrine falcons and protected what seemed a lawless wilderness. Sharing binoculars, Dan and the kids followed a flight of wild ponies across a field, but my eyes dared not leave the curves of the craggy coast. Reed-thin roads zigzagged through unpaved turf or bogland. Losing focus for two seconds might land us in a ditch, mired down for the night without a pillow.

Bogged Down

I slammed on the brakes, as a fox dodged our tires with a shrill bark. Its fluffy, white-tipped tail mocked us before I lost control of the car and skidded off the road. I held my breath as we bounced in our seats, and the car jolted to a dizzying stop.

Dazed, I swung the steering wheel to the right, turning our wheels away from soggy brown ground. But the car wouldn’t budge. The back tires spun, sending dirt and moss flying each time I accelerated.

“Stop! You’re digging us deeper into the bog!” yelled Dan, his voice bristling. I knew he was annoyed about losing time, but I liked the idea of being bogged down for a while. Instead of hugging the road, why not embrace the land?

We climbed out of the car, stepping onto a cushiony carpet of chocolate-brown bog moss. As I inhaled delicate scents of bell heather and pimpernel, I hoped nature would soothe Dan’s nerves.

Our car was stuck in a patch of waterlogged moss and grass laced with yellow-tinted lichens and triangular-stemmed sedges of russet and pale pink. I kneeled and touched the soft, watery turf engulfing our back tires. It felt smooth and malleable, reminding me of Seamus Heaney’s poem, “Bogland:”

The ground itself is kind, black butter

Melting and opening underfoot

I turned to see my son jump up and down on the quaking earth, starting a chain reaction as trees several feet away bobbed in sync.

Bogs were Ancient Burial Sites for Human Sacrifices

“Matt, don’t jump so hard,” I warned, recalling that bogs were ancient burial sites for hundreds of human sacrifices to the goddess of fertility. “We don’t want to lose you.”

But I couldn’t help wanting to lose myself. This is where I wanted to linger, to be more in the moment, far from familiar neighborhood faces and routines. I didn’t need a plan, and a map would just get in the way.

Dan, however, was bent on debogging our wheels from the unrelenting ground. His blue shirt was soon sprinkled with dirt, as he dug around the rear tires with a stubby branch.

Then he tied a white rag found in the trunk to the radio antenna to flag down help. But we’d meandered off the main road, and help seemed way out of the picture. I wondered how far one of us would have to walk to find bogside assistance.

I tried calling O’Donoghue’s farmhouse in Limerick to confirm tonight’s room, but cell signals were nonexistent. Daylight was fading. I imagined the four of us spending the night in our PT Cruiser: scrunched up against one another, with no food, water or blankets, stuck on unfamiliar turf.

A Weird Wetland Where Puffs of Bog Cotton Blew in the Breeze

The best way to help Dan, I thought, was to keep the kids busy and out of his way. With both kids in tow, I ventured further into this weird wetland while Dan collected rocks, bark, and branches for tire traction. We walked over spongy turf, following puffs of bog cotton blowing in the breeze. I encouraged Matt and Christie to squish the marshy soil between their fingers and to smell the decaying plant material.

“It stinks like the compost pile in our backyard,” said Christie, as she quickly stepped away.

Not wanting to be downwind of the stagnant puddles, I led a fox hunt in the opposite direction. On scrap paper, I drew a picture for Christie and Matt of a diamond-shaped fox track with four toes on each foot, as well as claws, pocketing the emergency whistle carried in my handbag just in case. I told the kids to yell or clap their hands during a close encounter, since foxes tend to flee rather than fight.

Dan, meanwhile, had put a few coffee cups full of pebbles and sand from the nearby shoreline under our car’s rear tires. The kids and I trekked back to the car and climbed in. I revved the engine while Dan strained to push the car forward. Still no traction.

As a fickle light faded above, and the kids moaned they were starving, I worried about a long, cold night ahead on empty stomachs.

Our Rescuers Rocked our Car Out of the Muck

Soon we heard the rumbling of a motor. It grew louder as it drew closer. A red pick-up truck pulled up next to our bog-splattered car. A young couple jumped out, asking if they could help.

My spirits soared, relieved that my prayers had been heard. The guy, who wore a classic green, white and orange rugby shirt, dragged two large sheets of plywood from his truck’s cargo space.

He slid a sheet under one back tire, while she slithered one under the other. Dan and the rugby player rocked our car back and forth while I started the engine. After several tries, the PT Cruiser lurched out of the muck.

“You’re sucking diesel now, mate, and it’s all good,” said our young hero, wiping dirt from his brow.

“Great teamwork,” said Dan, slipping them a tip, as they all shook hands. “Looks like Limerick’s back on the map.”

A Wild, Open Space Where God Had Painted with Gentle Strokes

I cheered our rescuers, who headed off in their truck, leaving behind deep tread marks. I glanced at Christie, Matt’s and my hands, our grimy nails proof we had romped on nature’s playground. Pieces of moss clinging to the back windshield reminded me of more than our battle with the bog.

Time had stood still for me this afternoon in Connemara. I looked out over this wild, open terrain, where God had painted with gentle strokes and soft hues. How fortuitous to have experienced a small chunk of it in fine detail.

I listened for the pounding hooves of ponies, felt the sea spray on my cheeks, and watched lofty peaks pierce the clouds. I smiled, thinking of the wise old man, who’d said Sky Road will stay with me forever.

If You Go:

Don’t miss the stunning landscape, wildlife, and the walk to Diamond Hill. Go at your own pace, as you take in the towering Twelve Bens’ peaks in the distance.

Clifden Castle was built in 1812 by John D’Arcy, founder of the town of Clifden. The castle today is a mere stone shell accessed through a gateway arch from Sky Road. Stroll a winding path to the castle where you’ll observe mock standing stones that D’Arcy erected as a legacy for his family.

A top-of-the-line dining experience in Clifden, especially if you enjoy fresh local seafood, friendly staff and ambience.

Read More:

Author Bio: Dorothy Maillet is a writer and adventurer from Irvington, NY. Her travels have taken her across Europe, Asia, Africa and North America. She has been a freelance feature writer for Gannett Newspapers, and her stories have appeared in the anthology, A Pink Suitcase: 22 Tales of Women’s Travel, Pembrokeshire Life (Wales), BootsnAll Travel, Westchester Life, and Go World Travel Magazine.

- 12 Cool Things to Do in Tbilisi, Georgia’s Vibrant Capital - April 29, 2024

- Travel Guide to Spain - April 28, 2024

- Travel Guide to Scotland - April 28, 2024