As the legend goes, St. Augustine’s Monastery in Erfurt, Germany, is where Martin Luther trained as a monk after he came perilously close to being incinerated by a lightning bolt, prompting him to devote his life to God’s service. Inside what’s now a Lutheran meeting and event space, the public can see the cloisters where Luther walked in silent meditation, the chapter room where he publicly confessed his sins, and the simple church where he worshipped.

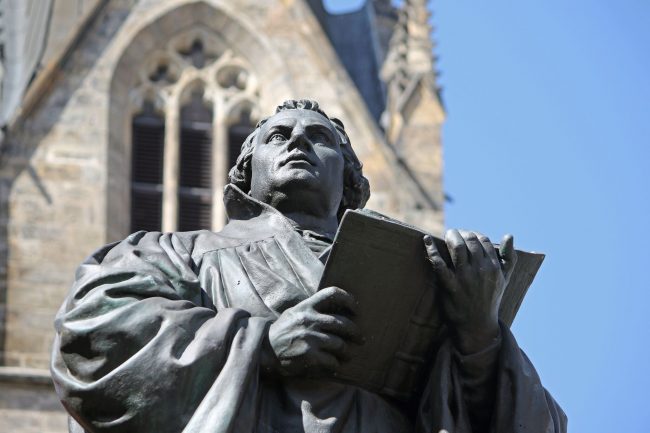

Following Martin Luther’s Footsteps in Germany

Earlier this summer, I found myself standing on the altar of that church while traveling in Germany, looking at the beautiful stained glass windows adorned with white roses. Was it possible, my guide speculated, that Luther chose the white rose as his symbol because of this window?

Then my guide casually mentioned that the entire night before his ordination, Luther lay in the shape of a cross atop a tomb embedded in the altar’s floor. That tomb was inches from my feet, and looking at it in this quiet, contemplative space, I felt a shiver run through me. I could visualize Luther lying on that very spot, and even across five centuries, I was moved by his devotion.

500th Anniversary of the Reformation

The depth of my emotion astonished me. I’d come to Germany as so many thousands of other people are doing this year to observe the 500th anniversary of the Reformation’s beginning — it was in 1517 when Luther famously nailed his 95 theses to the church door in Wittenberg.

I knew very little about Luther before I arrived, nor — truthfully — did I have much interest. Though I was raised a Protestant, the man who initiated the break from Catholicism was a historical enigma to me, and not one I had much passion for learning more about.

Instead, I’d read that the cities in Germany where Luther lived and worked are unspoiled gems, pristine time capsules with half-timbered architecture and lots of bratwurst and good dark beer. So I thought I’d use the Reformation anniversary as an excuse to immerse myself in German culture. I didn’t expect to be moved by the story of a man who singlehandedly changed history. I didn’t expect to get a sense of him as a human being. And yet as I traveled from one city to another, that’s exactly what happened.

Erfurt, Germany

Erfurt certainly qualifies as one of those unspoiled German gems. Its central city is one of the best-preserved clusters of medieval and Renaissance architecture in Germany. Half-timbered structures, a few sagging in places as though they’d started to melt and then solidified, stand side by side with Renaissance townhouses adorned with golden crowns, golden wings, golden eggs. Gargoyles, including a set exemplifying the Seven Deadly Sins, are everywhere. Sleek modern street cars slither like red and green snakes through the cobblestoned streets. There’s even a substantial number of Art Nouveau structures thrown into the mix.

The point isn’t how much contrast there is, but rather how everything blends into a seamless, charming whole. Should you visit, you could do worse than just wandering aimlessly through the winding streets of this extraordinarily lovely city, happening on such gems as the Merchant’s Bridge, a 400-foot-long structure that, like Florence’s Ponte Vecchio, is lined with artisans’ shops.

When you emerge into the huge central square, actually one of a number of beguiling squares, you may well have the wind knocked out of you — atop a hill overlooking it stands an imposing Renaissance fortress alongside two beautiful churches, one of them the cathedral where Luther was ordained.

Erfurt is one of those fairy tale cities where there’s astonishment around every turn — It was exactly the type of place I’d come to Germany to see. Yet it was also a place where I could now imagine Martin Luther in his monk’s cowl striding through its streets.

Visiting Eisenach, Germany

“My beloved city” is what Luther called the town of Eisenach, where I had my next soulful stirring. It was a town important to him at two points in his life, the first when he was a young boy and attended the local grammar school.

What’s called “The Luther House,” where he boarded with a local family, is now a museum focusing on Luther’s translation of the Bible into German, a potentially dry subject but one I found quite absorbing.

I learned that Luther was so intent on getting the translations right that he not only consulted experts in Greek, Latin and Hebrew, but also butchers for Biblical passages referring to meat — he wanted to find just the right word, and when one didn’t exist in German, he made it up.

His invented vocabulary and metaphors still pervade modern German, just as the King James Bible does in English. Elsewhere in the museum are exhibits on his influence on German music, especially on Bach, and on German literature — Bertold Brecht, an atheist, admitted that no other work of literature had greater influence on him than Luther’s Bible.

While I was intellectually stimulated at the Luther House, I wasn’t emotionally moved. Nor did any shivers go up my spine at the other place in Eisenach where modern-day pilgrims frequently find it happening — the magnificent castle on a mountain overlooking the town.

Wartburg Castle is where Luther spent time in Eisenach as an adult after the pope labeled him a heretic and an outlaw, basically declaring “open season” on him after his refusal to recant at the Diet of Worms.

His powerful protector, Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony, had Luther kidnapped and brought to Wartburg where he spent 10 months hiding out, disguising himself as “Squire George,” letting his hair and beard grow and wearing aristocratic clothing.

The simple “Luther Room” in the castle, the place where he got started on his Biblical translations, is a place of reverence for Luther devotees, but oddly, I was little touched by it. The only item in the room that was there during his stay is a huge whale vertebra, which he used as a footrest.

It’s said that Luther threw a pot of ink at the wall in this room while wrestling with the devil, but many regard this tale as apocryphal and the ink stain disappeared long ago. The room was also musty and dimly lit — maybe that too contributed to my inability to connect.

But then — wham! — another emotional encounter, and as so often happens, it came when least expected. I’d gone back down the mountain into Eisenach and made a stop at St. George’s Church, the stately church presiding over the town’s main square. Luther sang in the boys choir there as did Johann Sebastian Bach, born in Eisenach two centuries later.

I was staring at the pulpit where Luther may have preached, the baptismal font where Bach was christened just underneath it. I was surrounded by fellow tourists I’d just seen at the castle or around town. Suddenly, the magnificent organ up in the loft unexpectedly swelled with soul-stirring music so sublime I burst into tears, not just because of the music, but because of a sense of convergence.

I felt a connection with Luther, with Bach, and with the tens of thousands of visitors across the centuries who’ve been touched by this spiritual place. It felt as if the man who’d composed “A Mighty Fortress is Our God” was there, just out of sight.

Churches in Meissen, Germany

Perhaps not surprisingly, other emotional encounters took place inside churches. In Meissen, a city better known for its exquisite porcelain, I heard an unforgettable choral concert by the Bach Society of Houston with voices so harmoniously balanced they reverberated throughout the gorgeous Meissen Cathedral.

I met Reverend Robert Moore, also from Houston, a pastor with the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America, who’s serving as a “Reformation ambassador,” welcoming groups from the U.S. I came away with the sense of how many thousands of pilgrims are making their way to Germany this year in a form of spiritual quest. A bit belatedly perhaps, was I becoming one of them?

And inside the simple castle church in Torgau, it was another organ concert that stirred me. This town where Russian and American troops first shook hands in the waning days of World War II is yet another architectural gem with hundreds of medieval and Renaissance structures, including the spectacular Hartenfels Castle with its very plain chapel.

It was there I found myself having another connection with Luther — It’s deemed the first Protestant church and was consecrated by Luther himself in 1544. Torgau also has associations with Luther’s wife, Katarina von Bora, who died here after an accident in a horse cart. I learned of the Luthers’ happy marriage, his devotion to his children, his playful side — he referred to his wife as “Herr Käthe,” Mr. Katie, since she supposedly wore the pants in the family.

Oddly though, the churches of Wittenberg, the city where Luther spent the bulk of his life and career, left me untouched. Yes, there’s that famous door at All Saints Church where he nailed the 95 theses, but the door itself is long gone, destroyed in a fire in 1760. What’s been rebuilt is a monument — huge bronze doors with the 95 theses inscribed on them.

The nearby St. Mary’s Church, where Luther preached as many as 3,000 sermons, also gave me no sense of connection with the man, in spite of the beautiful artwork by Lucas Cranach that depicts Luther and his contemporaries as participants in the Last Supper.

Similarly, the Luther House, his Wittenberg home, didn’t much resonate with me. It’s gigantic — he lived there with as many as 50 other people, including relatives, servants, and student boarders. But there’s little sense of it being a family home, mostly because it’s now the world’s largest museum devoted to Reformation history, filled with hundreds of fascinating documents and artifacts — even a chest for the collection of money to purchase indulgences, the very issue that got the Reformation rolling. I learned so much there about how the Reformation began and then spread like wildfire from its source in Wittenberg.

Still, I just couldn’t imagine the Luther family inhabiting these rooms. The Lutherstube (Luther Room) came the closest. It’s the chamber where he retreated after dinner to discuss important matters of the day with students and guests. The windows, paneling, and flooring are of the period, but there’s not much furniture, making it hard to visualize a room full of people hanging on the Great Reformer’s words.

But afterwards, when I went to an adjacent building to see a special exhibit called “95 Treasures, 95 People” I felt like I met Martin Luther himself. The exhibition is indeed filled with treasures — Luther’s writing set, his will, even the pulpit from St. Mary’s Church where he preached those thousands of sermons. Many of these artifacts will be moved back inside the Luther House when the exhibit closes in November.

And then I found myself standing in front of Luther’s monk’s cowl, perhaps the one he was wearing when he refused to recant at the Diet of Worms. Looking at it, I began to visualize a human form inside that plain garment.

I felt as though I were face to face with the complicated individual whose conscience and convictions allowed him to take a stand against one of the most powerful institutions of his day. I’d learned so much in the preceding days that I was seeing him as far more than the learned scholar people traveled hundreds of miles to hear, a man dedicated to bringing the spiritual into the lives of everyday people.

He was also a lover of music, a devoted father, even a gregarious teller of bawdy jokes whom I’d been told left a substantial unpaid tab at his favorite bar when he died. So I knew him to be as complex a human being as any of us, not just a towering faceless figure who changed history.

So mission accomplished. I’d gone to Germany for an immersion into its captivating culture. I’d seen the towns that are like time capsules into the past. I’d had the many bratwursts and dark beers I’d hoped for. And quite without meaning to, I’d become a convert — I was enthralled, and likely always will be, by the story of a man who made life different for all us simply by nailing some world-changing documents on a church’s door.

If You Go

October 31, 2017 is the actual date of the 500th anniversary of the day Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses to the church door in Wittenberg, traditionally understood to be the date the Reformation began. A variety of special exhibits and events have been taking place throughout Germany this year to mark this event, with many of the exhibits closing in early November.

However, the sites associated with Luther will continue to be available for visits by tourists, and other events will be opening during what the Germans are now calling “The Luther Decade” as other events during the Reformation celebrate their 500th anniversary. Since Martin Luther lived and worked in a variety of cities in east-central Germany, a couple websites serve as “one-stop shops” to get information across the region. These include:

The bulk of the cities of the cities significant to Luther are in the German states of Thuringia, Saxony, and Saxony-Anhalt. For more information on cities and attractions in these states, go to:

Author Bio: Ohio-based travel writer Rich Warren travels the country and the world looking for offbeat and off-the-beaten-path stories. He’s a graduate of the Elf School of Iceland and also has searched for leprechauns in Ireland and gone on a ghost hunt in the house where the Lizzie Borden murders took place. His work has been published in the Chicago Tribune, Dallas Morning News, Cleveland Plain Dealer, National Geographic Traveler, AAA Home and Away, AAA Highroads, Ohio Magazine, Country Living, American Way, The Saturday Evening Post, and others.

- The Low-Key Magic of Ghent, Belgium - April 22, 2024

- Discover the Hidden Charm of Extremadura in Spain - April 20, 2024

- Life of a Champion: Exploring the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville - April 19, 2024