Go World Travel is reader-supported and may earn a commission from purchases made through links in this piece.

At 4:30PM on April 14th, 1861, after nearly 34 hours of concentrated bombardment from the surrounding Confederate batteries, Major Robert Anderson lowered the flag of the United States of America and he and his beleaguered Union command marched out of Fort Sumter to the tune of “Yankee Doodle Dandy” with their heads held high. Thus began 4 years of intra-familial horror.

Exactly four years later, Anderson stepped towards the flagstaff of the nearly unrecognizable fort where he and several survivors of that day raised the very same, bedraggled flag to the top of the 150-foot-tall flagstaff. As it unfurled and snapped to attention, the band played “The Star Spangled Banner”.

Nearly 161 years later, as Park Ranger James Drass shared these facts with us under a warm mid-morning sun, 14 volunteers, including my wife Kathy, stood by holding the United States Flag while a Marine Corporal on-leave grasped the halyard.

At Ranger Drass’ signal, the corporal heaved on the line which lifted the flag upwards and out of the reverent hands of its guardians.

Fort Sumter

As the flag reached its peak and was tied-off, Drass spoke passionately for several minutes as to what the flag meant and the significance of the continued unity of the States of America that those 4 hard-fought years had wrought.

“We are a diverse country. There is no doubt we will have differences. But despite those differences, we are all Americans. We should never forget this” It was a moving moment for all of us in attendance and not one that will soon be forgot.

We had started our visit earlier that morning at the Fort Sumter Visitor Education Center at Liberty Square along the waterfront of Charleston, S.C.

Fort Sumter sits on a 2 1/2-acre island in Charleston Harbor and is only accessible by boat. We had decided to walk to the Square that morning. Misjudging the length of our walk, we hurried the last several yards in order to catch the first ferry of the day.

Spirit of The Lowcountry

Our water-borne transference this day was the Spirit of the Lowcountry, a modern interpretation of an early side-wheeler. Its 3-decks of understated charm were our time-machine to a much earlier time.

We settled into chairs on the upper deck which provided a great vantage point to see Charleston by water. The views from the boat are beautiful. The trip itself takes about 30-45 minutes.

As we sailed The Charleston Harbor, we neared Shutes Folly, a small island which is home to the little-known Castle Pinckney, a deteriorating 19th century fortification. We also sailed passed Patriot’s Point, home to the USS Yorktown, one of 24 Essex-class aircraft carriers built during World War II.

As we continued along, a volunteer provided running narration about the harbor, the sights and, especially, Fort Sumter. He went into more detail about its role in the Civil War and how the war affected Charleston.

Historic Fort Sumter

By 1861, Fort Sumter was a looming presence that consisted of an unfinished five-sided stone masonry fort with 55-foot tall walls. Two tiers of gunrooms lined four of the fort’s walls. Officers’ quarters, three barracks buildings and a parade ground completed the grand structure.

As tensions between North and South escalated in December 1860 with the secession of the state of South Carolina, Major Anderson and his 85 troops occupied the unfinished fort. At that time, only 60 out of the planned 135 cannon were mounted and in place.

On the morning of April 12, 1861, tensions finally reached the breaking point. At about 4:30 a.m., a mortar shot arced into the air and exploded over the fort as other Confederate batteries joined in and opened fire on Fort Sumter. After facing a severe bombardment, the Union-held fort surrendered the following day.

Upon capture, Ft. Sumter was the South’s symbol of defiance and had to be defended at all costs. It was a symbol of secession for the North, and had to be taken at whatever the cost.

Over the next 4 years, the union made several assaults and fired nearly 50,000 projectiles at the fort. Confederates held Fort Sumter until February 1865, only weeks before the surrender of General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865.

As our boat docked at the wharf, I was surprised at what we encountered. Although the aged masonry-and-brick walls are still there, the exterior of the fort retains little of its appearance in 1861. When I asked the ranger about this, he stated that Union artillery had effectively reduced it to a standing pile of rubble.

The damage wrought and the simplistic Confederate repairs to Fort Sumter had transformed the former three-tiered brick-and-masonry monolith into a barely recognizable shell of its former self.

Today, a red band around the flagpole several dozen feet above our heads marks the height of the walls before the Civil War began.

Inside Fort Sumter

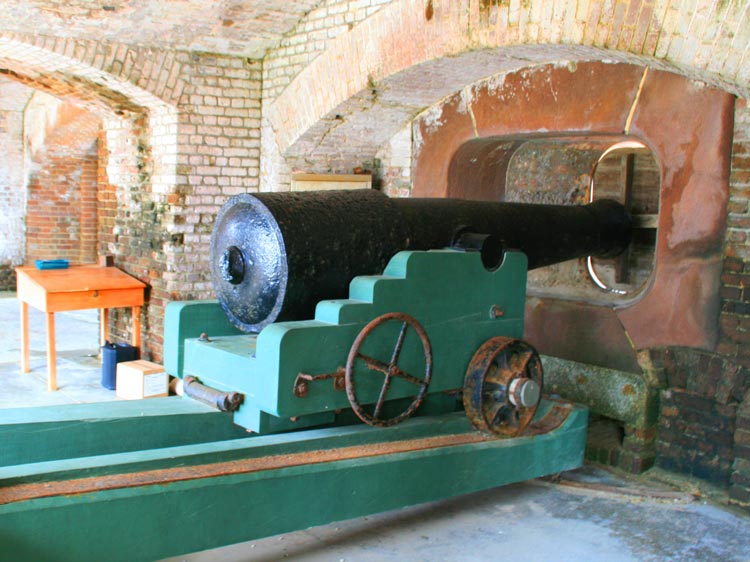

Inside the walls, several huge, black cast-iron cannon are on display throughout the grounds and in the cavernous casements (gunrooms). One, a 15-inch Rodman cannon with its oddly bottle-shaped appearance, weighs in at over 50,000 lbs. and could toss a 400 pound shot over 2.8 miles.

Nearby, the unrepaired brick ruins show the devastation inflicted during the course of the war. A rusted artillery shell lay embedded in one of the damaged walls. It is one of at least 4 shells that remain impacted in the brick.

The interior parade ground has changed dramatically. Battery Huger, a large black and unsightly concrete structure, was added in 1899 during the Spanish-American War.

Designed to protect Charleston Harbor from naval surface attack, it mounted two breech-loading guns, which fired 1,000 pound shells. Today, it’s ugly distracting, dark presence houses restrooms and a small, but informative museum.

Greatest National Conflict

Today, viewing the serene surroundings, it’s difficult to imagine what the occupants, of both sides, must have endured during the course of the 4 years of the steady destruction by shot and shell.

I stood atop of the grassy mound of earth that effectively covers a portion of the ruins, and gazed across the harbor towards Charleston and wondered of its inhabitants as they stood on rooftops some 161 years ago and cheered as shells plunged into the citadel.

Believing, as they did, that the war would be short-lived, I wondered if they ever considered the eventual outcome— and its consequences?

That same thought occurred to me as we slowly returned across the harbor past the forlorn looking Castle Pickney. It’s was long ago reclaimed by nature as trees, brush and vines enveloped the walls.

A roost for scores of Pelican’s and abandoned by both state and federal authorities, a lone flag pole stood upon it with its Stars and Bars, a flag of the Confederacy, hanging desolately over the grounds.

Abraham Lincoln said, “The last ray of hope for preserving the Union peaceably expired at the assault upon Fort Sumter…” Today, the broken ramparts of Fort Sumter stand both as the genesis of our greatest national conflict and of the nation’s great resilience.

Book This Trip

- Tours begin from Liberty Square in downtown Charleston, S.C. or Patriot’s Point, Mount Pleasant, S.C.

- Adults $32.00

- Seniors/Active Military $29.00

- Children (4-11) $19.00

- Together at Sea: A Mediterranean Family Adventure - April 27, 2024

- Travel Guide to Colorado - April 26, 2024

- Travel Guide to Croatia - April 26, 2024