The United States Embassy, at the time, was closed. We’d looked through the gates of it during our visit and saw no signs of life. If there were any personnel staffing it, they weren’t exactly rolling out the red carpet.

My traveling companions and I held our breath as we awaited the results of our rapid virus test.

The tests were conducted alongside a small kiosk at the end of the departures area of Havana’s Jose Marti International Airport terminal. Tim, Matt and I were lucky we arrived in the dark at 6 a.m. just as the terminal was opening because we’d waited half-an-hour in a five-person line to, one-by-one, to get the nasal swab test. That same line behind us, as the morning sunlight only started to stream through the terminal windows, now had 50 people standing for what would be an excruciatingly long wait and potential missed flight.

Only two women were working at the testing kiosk. In no noticeable hurry one of them alternated between registered people, taking passports and a $25 payment, and completing the forms after the test. The other, after occasionally climbing up on a chair to pull down crates of testing kits, administered them on a plastic chair partially hidden beside the kiosk. I was astonished that while I was being tested with the nasal swab a janitor was mopping the floor right below me!

After about 10 minutes the same woman who administered my test called my name and handed me my passport and the results.

“Very good,” she said in broken English.

I was relieved and as I walked away, I opened the passport and paper just to have a look at the results.

The passport and results were not mine.

Luckily, I’d been handed the passport and information of my traveling companion Tim. He was lingering for Matt and I so we could all walk to the airline check-in counter together. Tim hadn’t bothered to look at his results because the woman told him he was negative, so he was surprised when I told him I had his passport. I was relieved when he opened the paperwork and found he had mine.

What would have happened if my passport and test results had been accidentally given to a stranger who didn’t notice and then got lost in the human swarm of people going through that Havana airport?

I was so nervous about the virus result that I considered tipping the registration lady and the test-taker to try to ensure a “negative result” before she administered it. Why? And why were each of us holding our breath almost on our knees praying for a negative result? The answer is complicated but, after four days, it was time for us to leave Cuba. A positive virus result would have been a disaster.

Navigating with Nothing

Not being allowed to board that American Airlines flight to Miami because of a positive virus test would have presented a very complicated situation for Matt, Tim or myself. None of us would have wanted to leave anyone behind, so thank God we all tested negative and it didn’t come to that. A situation like that could have provoked lots of guilt and may have strained our friendships.

Why was the prospect of being forced to stay behind in Cuba so dreaded and complicated?

First off, none of us had any money left. We’d used up all of the Cuban pesos we’d purchased on arrival because the Cuban peso has no value anywhere outside Cuba and even inside Cuba cannot be exchanged for other currencies. Use it or lose it.

We’d had to convert our U.S. dollars to Cuba pesos upon arrival because American money was not accepted anywhere. The huge pile of paper Cuban pesos piled on our kitchen table was dispersed between the three of us. Walking around money meant a wide wad in your pocket which looked like it was worth a lot more than it was. After dinner, for instance, we would count out the 40,000-peso tab in denominations of 100 and 200-peso bills. We made piles on the table in order to keep track.

Our U.S.-issued credit and debit cards were useless. So, by the end of the four-day visit we’d given away what we hadn’t spent. There were plenty of opportunities to give the money to street performers, musicians and restaurant servers. Whatever American money I held in reserve in my wallet was useless unless I could convert it to Cuban pesos.

So, challenge number one was we had no money – and no access to money.

Cutoff From Communication

Problem number two was that our American-based mobile phones had extremely limited and unreliable connectivity. When we did happen to find rare cellular usage areas it was extremely expensive. For instance, one brief, less-than five-minute call from Matt to his wife back in the states cost $50. Occasionally we found pockets of wireless internet through a log-in page, but there was no ordering up an Uber or even phoning up a taxi for Americans in Cuba.

I suppose we could have gone downstairs to the baggage claim entrance and found taxi drivers for hire…and maybe we could have exchanged what little American money we had if we could have found an airport currency exchange, but where would we have had them take us? Havana’s most notable hotels are off limits to Americans due to the U.S. trade embargo – which the Cubans refer to as a “blockade.”

The United States Embassy, at the time, was closed. We’d looked through the gates of it during our visit and saw no signs of life. If there were any personnel staffing it, they weren’t exactly rolling out the red carpet.

Our guide for the entire trip, a Cuban-born American friend named Felix Sharpe Caballero, encourages collaborative relations between the USA and the Republic of Cuba. He told us before dropping us off at the airport that if any of us happened to test positive he’d find us accommodating at his 13-story walk-up apartment (the elevator doesn’t work)…or with a relative in the city with no running water. Gracias, amigo!

Dose of Reality

Without money, communications or mobility, we would have been stuck. And even throughout the rest of the airport (which took lots of patience to get through with long check-in and bag check lines, immigration and security waits) we were limited in that none of the sparse shops, bars or coffee stands would take American money, credit cards, or even Cuban pesos. (Euro was accepted, and if I had it to do over again, I would have tried to use Euro throughout Havana.) But for us, no food – no drink – and toilets without toilet seats (a balancing act we’d become accustomed to throughout most of Havana.)

One aspect of Cuban life we did not become comfortable with was the Cuban government’s insistence on pandemic face mask wearing – even outside! A walk along Havana’s famed scenic, oceanfront Malecon required mask wearing. Ironically with a fork or drink in one’s hand in a restaurant or bar – indoor or outdoor – all masks were off.)

We stayed in a private-housing high-rise condo on the sea – allowable by U.S. law – but with no convenience stores or markets we had no ability to stock the refrigerator with basic necessities so it was a spartan existence. Even cigars seemed hard to come by.

I realize for blessed Americans like us this is considered a “first world problem” – a fact enhanced by our only temporary existence observing what third-world communism is really like. Each day we’d purchase extra cans of soda, rum and beer in bars to take back to the condo.

Viva Habana

There were moments in and around Havana, including in the upscale Miramar area that is home to many of the international embassies, during which it was easy to forget that the pandemic plus political sanctions and the communist government have created challenging conditions for the Cuban people. An elegant waterfront restaurant called the Vista Mar operated next to a crumbling, abandoned mansion. A chic coffeehouse was attached to a bumping nightclub with colored strobe lights flashing to the American hip-hop music the dj was playing.

The view of Cuba’s restored, glittering capitol dome (similar to Washington’s but taller) is breathtaking from the rooftop, poolside restaurant atop the bustling hotel across the street. From that rooftop dilapidated buildings were also visible and just around the corner from the famed Floridita – the classic club-style bar which calls itself the “cradle of the daquiri.” While live bands play Cuban music tourists line up to take pictures with the life-sized statue of one-time Havana resident and literary giant Ernest Hemingway.

La Bodeguita del Medio is the other Hemingway hangout in Old Havana where “Papa” drank mojitos. It was full of British tourists when we sampled a few of the rum, lime, sugar and muddled mint concoctions.

Finca Vigia, Hemingway’s house outside Havana, where his beloved boat the Pilar is also on display, is a treat to tour. Cojimar, the nearby small fishing village that was the inspiration and setting for Hemingway’s Old Man and the Sea, sadly, has become a shuttered ghost town lorded over by a bust of Hemingway in a raised pergola.

Sightseeing

The boisterous spirit and constant cheering displayed by the fans at an afternoon professional baseball game was astonishing…as was the youth baseball practice at which I watched the players pitching and hitting old baseballs sometimes held together by duct tape.

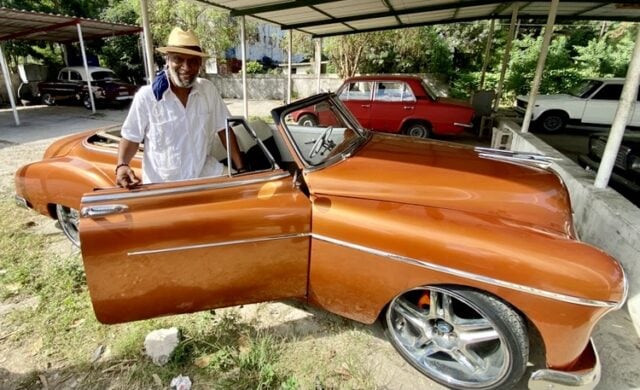

The Cubans also find ways to hold together the working, 1950’s colorful classic cars that populate and decorate its streets and neighborhoods with chrome and tailfins.

It was a bit intimidating to see the beret-wearing Cuban police, uniformed in Castro-colored drab olive green, guarding the historical vehicles – exhibited outside the Museum of the Revolution. I could not resist making eye contact and waving to the serious-faced, silent soldiers. Each of them looked startled that I would wave to them and then, with awkward but heartwarming humanity, managed to give a tiny, discreet wave back.

In fairness, the vehicles on display in the garden were somber in nature: the Granma Motor Yacht used to transport revolutionaries; Fidel Castro’s bullet-hole-riddled jeep; a Soviet tank used to battle the Bay of Pigs invasion; and the remains of an American U-2 plane the Cubans shot down.

Warmer Welcome

We received a much more effusive welcome from Padre Ariel Suarez Jauregui, a Catholic priest who spotted us while saying Mass at Iglesia Nuestra Señora de La Caridad and welcomed us by pointing us out as visiting Americans in front of the entire congregation during the service.

My favorite meeting was with a 12-year-old Cuban radio performer named Marian Garcia Pupo. Her mother Maria Pupo, a friend of Felix, introduced us at her home in Havana. Marian was initially reserved and polite but when I asked her to display her radio performance style, she lit up and spoke with the confidence, professional poise and enthusiasm of a true broadcasting star.

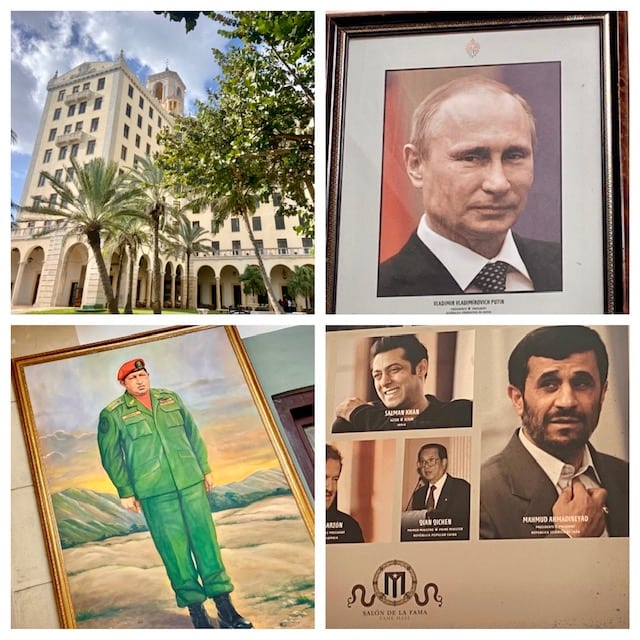

Every Cuban we met was friendly and eager to speak with us. A tuxedoed bartender at the Nacional Hotel was delighted when Tim gifted him a Detroit Lions t-shirt. On the wall above the bar: portraits of dictators Vladimir Putin of Russia; Venezuela’s late Hugo Chavez and former Iranian president Ahmed Ahmadinejad.

Cuban diplomat and ambassador Ines Fors Fernandez agreed, thanks to an introduction by Felix Sharpe Caballero, to meet with us in her office at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

“My mother always reminded me ‘What you have done in your life is because of Fidel Castro.’ Almost everything I have is because of the Cuban Revolution. I am proud that I am a diplomat from a humble family because of Fidel,” said Fernandez. “I had the opportunity to meet him many times. It was unforgettable. He is one of the most important persons of the 20th century”

Fernandez and her colleague, Ariel Hernandez Hernandez, joined Tim, Matt, Felix and I for dinner.

Later in the week we had tea with Sandra Yisel Ramirez Rodriguez, who directs the ICAP – the Cuban Institute of Friendship with the Peoples.

“You will always find friendly Cuban people to welcome you here,” she insisted. Then she dismissed the suspicion that American diplomats at the embassy had been harassed and sickened by some type of targeted noise sonic warfare. “There is no such thing as the so-called ‘Havana Syndrome.’ That is science fiction. We don’t have a technological device like that.”

Along the way we also met two gorgeous young dentists who, under the communist system, earned slightly more than an American dentist might spend on mouthwash each month. Our driver for the week was a sharp operator and a resource.

Dine and Dance

The restaurants we dined in were colorful and fun with live music and lively servers. San Cristobal Restaurant was full of photos, letters and souvenirs of politicians who’d dined there – from Russian leaders to United States Senators. The chair used by American President Barack Obama was mounted to the wall with an American flag draped over it.

El Carbon, across from the former Presidential Palace (now the Museum of the Revolution) was also full of eye candy (decorations and people.) The Cuban band was outstanding and, for the 50th time, we heard a rendition of the catchy Cuban standard Guantanamera.

I noticed an unusually-named item on the menu and called the waitress over.

“What does this mean? What is this?” I asked her quietly while pointing at the menu item.

The brunette flashed her big, brown eyes at me and answered, “That is, sir, exactly what it says.”

Without alerting the others I secretly ordered the item. You can only imagine their surprise when the waitress eventually brought the item and set the platter in the middle of the table…with a “pigs’ head,” eyelashes, teeth and all, on it!

Read more on Michael Patrick Shiels’ travel blog, The Travel Tattler. Contact Travel Writer Michael Patrick Shiels at [email protected]