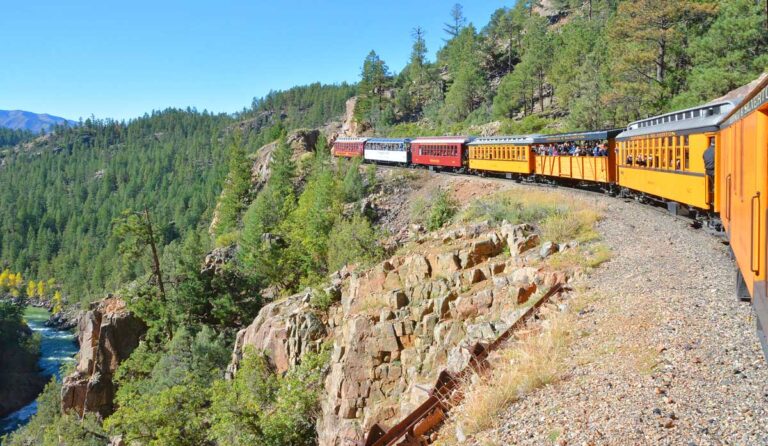

Durango-Silverton Railroad

We board the Durango train late, later than is comfortable because trains keep tight schedules. They will leave without you.

The Durango-Silverton Narrow Gauge is an 1890’s style coal-burning steam train. My wife and I are using it to access the backcountry near Silverton, Colorado high in the mountains of the southwestern US.

The train runs all the way to Silverton, but also lets passengers off and then picks up a few days later, allowing outdoors enthusiasts to fish the Animas River, camp or backpack even further in, like we’ll be doing.

I’ve been here before. We’re essentially making another pilgrimage. Vestal Peak and Arrow Peak are about 7 miles and several thousand feet of elevation gain from Elk Park, where the train drops us off. The ride saves us the 36 switchbacks we would have subjected ourselves to if we had elected to park at Molas Pass and descend.

The last time we were here, we counted every one of those 36, and then counted them again on the way out as we gained 2,000+ feet of elevation.

The time the Durango-Silverton train ride saves us is good. The last time we attempted Arrow Peak we were denied by the cold and repeated trouble connecting with the trail along Vestal Creek. We’re hoping for better luck now.

The train jostles along the tracks out of Durango and into the lower mountains. The engine nearly brushes the rock walls, many of which were dynamited extensively to make space during construction in the 1880’s. Its narrow track width allowed passage to mining encampments where standard width trains would have had difficulty.

The Beautiful River

The river is accessed at several points to give the train the water it needs to make steam along the climb to Silverton. As we chuff and whistle into the hills, the locomotive lets off sudden geysers of thick steam, purging itself of river sediment that could create wear on the engine. Coal cinders gently rain down outside between the covered cars. We pass close by the river, then high above it and back again.

The turquoise water is nearly ice cold, having been snowpack just hours earlier.

We’re dropped off along with a group of preteen backpackers and their guide, wearing a Telluride Academy t-shirt. What a field trip! I speak with the guide to clarify the situation with the trail – we follow an initial section different than the one from the pass – and he asks where we’re headed. The kids are hiking in the same direction as our route to the peak, but stopping at the prime camping spots near the beaver ponds.

When the camp guide is told that we’re headed back to Arrow and Vestal Peak, he perks up. He hasn’t been yet, but has heard stories. It seems everyone who’s visited the peaks reveres them, remains in awe of them, and tells their friends. Any of the people I’ve talked to about Vestal Peak and its north-facing Wham Ridge take a special ownership of the area, and I guess I do too.

I climbed Vestal with an Outward Bound expedition shortly after high school, but as much as I’d like to climb it, that’s not the peak we’ll be doing this trip. We’re not rock climbers, and we’re not outfitted with ropes and the necessary gear.

Vestal’s sister, Arrow Peak, is our aim, and it’ll be quite enough of a trial. It’s a similarly shaped upheaval of quartzite from the crust of the earth: triangular, sudden, and violent. While it’s not a technical ascent, it’s very much Class 4 climbing with frequent use of hands, lots of exposure, and plenty of places to die.

My wife, Jeanine, has historically feared heights to some degree, though she’s come around a little lately. I’m really hoping she’s game for the summit. I’ve downplayed the nature of the peak thus far in hopes I can gently cajole her to push her edge as she gradually realizes what we’re in for. For this reason, I’m not totally attached to the idea of summiting, though I’d certainly like to.

The Amazing Natural Beauty of Colorado

Wild flowers, aspen and ivy abound as we pass along the creek; it’s been green this year with lots of rain. And indeed it’s going to rain. It’s not if, it’s when. Afternoon thunderstorms are a certainty in the Rockies, and we know not to expect otherwise. This is why it’s so important to be off the peak by noon. Around 20 people are struck by lightning in Colorado every year.

As we stop to put on rain gear and pack covers, we’re passed by the group and their guide says, “Yep, it’s about that time,” as though he was awaiting its arrival with the same burdened certainty.

The rain in the Rockies is clean, cold and beautiful if you can stay dry. It’s usually brief and often followed by uncanny sunshine. You wish it away, denying it all morning, knowing it’s coming and hoping it isn’t.

The rain is inconvenient, and nobody likes dealing with wet gear, but when it passes it leaves a kind of uplifted giddiness in backpackers. The anxiety of getting wet clears into relief and sunshine.

This rain clears, but not before it hails. The hails hurts through the hood of our parkas. The torn red tarp I’m using in place of a pack cover continually falls off, and holding it in place makes my hands wet. Wet hands are cold hands.

We pass the first oncoming backpackers we’ve encountered just as the hail stops. They’ve been where we’re headed, and say they had the entire basin to themselves. These two men have the post-rain giddiness and are talkative, having been deprived of society for a week. We talk. I realize they have that same ownership of Vestal and Vestal Basin, like it’s a gift that was given to them and they want to share it.

They report mountain goats and the possibility of moose at the beaver ponds. We were hoping for mountain goats. These goats are spectacular, magnificent wild animals that want nothing more than to lick up human urine. They need the electrolytes, and are neither shy nor particular about how they get them.

The Colorado Trail

We meet the kids and their guide again at the beaver ponds where our trail to Vestal is departing from the Colorado Trail. He asks about the peaks again, if the trail to their base remains visible such as it is here, and if I think it would be a feasible day hike for the kids tomorrow. I say I think it’d be a go.

As we descend for a final crossing of Elk Creek I feel bad for telling him it would work for his group of teens. It won’t. The trail hits a steep, sliding section then requires a sketchy crossing on downed pines across fast-moving water.

The trail becomes faint as we climb, and we have trouble tracking it despite constant attentiveness. It’s difficult to tell if the patch of trail that we’re walking is “the” trail or just a game trail followed mostly by elk. The trail we’re following tapers off into the thick underbrush, leaving us to backtrack and attempt to locate “the” trail again.

Eventually, the canyon rolls out into a wide meadow, and we stop to camp. It’s late and we’re exhausted, though part of me wants to go further and spend the night above tree line. It would shorten our hike tomorrow when time is of the essence in avoiding the thunderstorms, and it’d just be cool to sleep in the high alpine.

That being true, the meadow is perfect and a spot near the trail is flat for the tent. We feel conscious of the delicate ground-cover we’re trafficking. Everything this high up is delicate and clinging to life. It’s so pristine that care should be taken.

The world is timeless and entirely ours as the sun sets behind the peaks to the north, and Vestal is the last peak to be illuminated over the rise. It’s a monumental temple constructed without human involvement, a golden spire in the dusk.

We fetch water from Vestal Creek which is so thickly vegetated as to make that difficult.

This high up in the mountains I have no qualms about drinking untreated water. It’s delicious. Iodine tablets or filtration are not necessary to avoid giardia because there is so little upstream, and in fact so little above us at all. It’s simply snowpack and spring water.

We awake to the goats. It’s as if they know hikers emerge from the nylon domes with the sunlight and that urine is a certainty at that time of day. Our phone batteries are nearly exhausted by the picture taking, and the goats give plenty of opportunity for shots.

I’m the first to emerge, and the goats are close to the tent, too close for comfort. The wild, horned animal walks directly toward me. It comes as close as 20 feet and I retreat back into the tent. Photos can wait.

The goats keep their distance as we eat breakfast, and we settle into an uneasy trust with the two animals. Breakfast does not involve the stove – cold cereal. This allows us to get moving more quickly; it’s past 6:00 am, and we’ll need to move fast to ensure we beat the afternoon rain.

At the base of the peak, we must mount a rock ledge that runs as a steep, wide ribbon most of the way to the summit. The initial obstacle here is a wakeup. My wife has difficulty with the maneuver – I have a big height advantage – and the danger of a 10-foot fall is immediate.

This may not sound like a big drop, but a broken ankle is real trouble and a head injury is a disaster this far in. I think to myself that we should really be wearing helmets, bike helmets if nothing else, goofiness be damned.

We proceed up the ridge avoiding water that’s flowing over the rocks. The stone grips very well when dry, yet turns to oiled glass when wet. This is another reason we must be off the peak before the thunderstorm.

The skies are mostly clear so far, and the altitude we’re gaining affords us an awesome view of Vestal’s sharp rise. Moving a little higher we can see Vestal Lake, teal blue with patches of ice remaining even this far into the summer.

The trail disappears entirely now and we’re climbing on all fours, managing one maneuver upward at a time, then scouting for the next point where we can safely move higher. I lead, and pick a spot between boulders that looks feasible. It is, but the spot it leads to isn’t one we can climb out of. We’re forced to backtrack and go around.

Jeanine is reporting mild low blood sugar dizziness. I suggest going back, but she thinks she’ll be fine if we stop to eat. We do stop, and watch clouds beginning to form in the northeast sky. She’s a trooper, but I can tell she’s approaching her limit.

Cresting a small saddle between the actual summit and a dramatic false summit spire gives her a second wind because the view of the other side of the horizon becomes available. Gray stone, snow, and sky is all that can be seen in the distance.

We drop our bags. They’re cumbersome, and we think we’re within 100 vertical feet of the summit. I’m confident we can find them again on the way back down. This helps, because the obstacles continue all the way to the top.

Atlast, We did it

We’ve done it, and I let out a holler. We’re 13,809 feet above the sea, and the world lays out 360 degrees around us with snowcaps as far as we can see. We kiss, take pictures, and pause for just a short time before descending. The clouds are still far away, but they’re darkening.

Going down is almost harder than going up because you can’t see footholds or easily assess what’s below you, but we make the descent without incident. The clouds have built up heavy now. It’s just a matter of time. We’re safe from lightning, but not the inconvenience of wetness.

Fortunately, the rain begins its first drops as we unzip the tent. The tent is a victory, and the timing of the rain a blessing.

We nap, we eat, we make little moaning sounds when we attempt to move. I’m so sore, despite a steady diet of Advil that I’ve put myself on since we got off the train.

As the rain clears, the meadow basin is illuminated with life, and we realize it’s all ours – we’re the only two people in the world. It’s Eden.

I go barefoot to the creek to fetch water and fully submerge my body in the cold. I lie flat in the shockingly icy water and grip the rocks to keep the creek from carrying me away as I put my head under. I’m reborn.

Not long after redressing we get our first visitors since departing from the beaver ponds. Our solitude is broken, but not by much.

I talk with the first of three packers as the other two come up from behind. He’s beardy, has kind eyes, and introduces himself with a handshake that implies we’re going to talk for a while. These guys are local to Durango and looking to climb Arrow as well in part of a longer trek that will drop them down into Needleton.

They offer us a beer. These crazy men are packing around beer this deep into the backcountry, possibly good beer in heavy glass bottles which they will then pack out again. It’s a burly, irreverent thing to be doing; whiskey would have been more space-efficient and much lighter.

After completing the trek back out to the train stop we sit by the Animas feeling fulfilled and victorious, enjoying the moment yet anticipating the food and the comforts of Durango. Stepping aboard the train, we begin the transition to civilization again.

We enter amongst the other passengers, distinguished from them for having gotten off for a greater adventure than just the ride to Silverton and back. We’re distinguished by our odor too.

Fortunately, a shower and another, more civilized adventure awaits us in Durango.

If You Go to Durango or Silverton

If you’re not going to backpack, at least get off the train and camp overnight. The ability to transport gear on the train means you can essentially car camp far, far from the road.

For more southwest Colorado adventure, check out the nearby ruins of Mesa Verde National Park.

Jack Bohannan is a freelance writer and outdoor enthusiast living in Denver, Colorado.