Go World Travel is reader-supported and may earn a commission from purchases made through links in this piece.

From everything I’d read while preparing for my trip to Kyrgyzstan, the primary point of appeal was the nature and landscape. Therefore, after a few days in the capital city of Bishkek, I took a bus east towards Issyk Kul lake.

It is the second-largest salt lake in the world, the Caspian Sea being the first, and a key player in the country’s biosphere.

Found in Translation

The driver of our marshrutka, the 15-seater passenger van, didn’t speak any English. However, his assistant Munya knew a little and was also eager to chat with me via Google Translate.

“Why do you travel single?”

“Where will you stay at lake?”

“When you return to Bishkek?”

For 4 hours, we swapped questions about each other’s respective countries and customs, one line at a time. During our rest stop, he pointed out the popular fish that people ate with their hands. It was dried and hanging up by the roadside. The smell alone was enough for me to avoid it.

Hitchhiking to a Viewpoint Near Bokonbaevo

We pulled into Bokonbaevo, the largest town on the southern coast of Issyk Kul Lake. By this time, Munya had convinced me to check out a beautiful viewpoint within walking distance of the center.

I grabbed my backpack from the trunk, waved to the van still half full of people, and followed my Maps.me app to the road leading to the vista point.

I strolled between fields of tall grass and flowers, with snow-topped mountains on both sides in the distance. On the way, I met two Austrian travelers heading for the same viewpoint.

However, when they took out their phones to show me we realized that it was, in fact, 13 kilometers away. Therefore, we unanimously decided to save time and hitchhike, a very common form of transportation in the country.

Luckily, a car pulled up not long thereafter and we squeezed into the back, with two teenage children in the trunk and the father of the family driving. The mother, who spoke a little English, excitedly told us on our bumpy ride about their home in the mountains.

“It going to be guesthouse for travelers! We have dog, cat, horse, see baby chicken?”. In an unexpected move, she opened a shoebox on her lap. Three baby chicks were revealed, bumping around and chirping as they traveled to their new home.

We couldn’t help but grin in the back at her contagious enthusiasm.

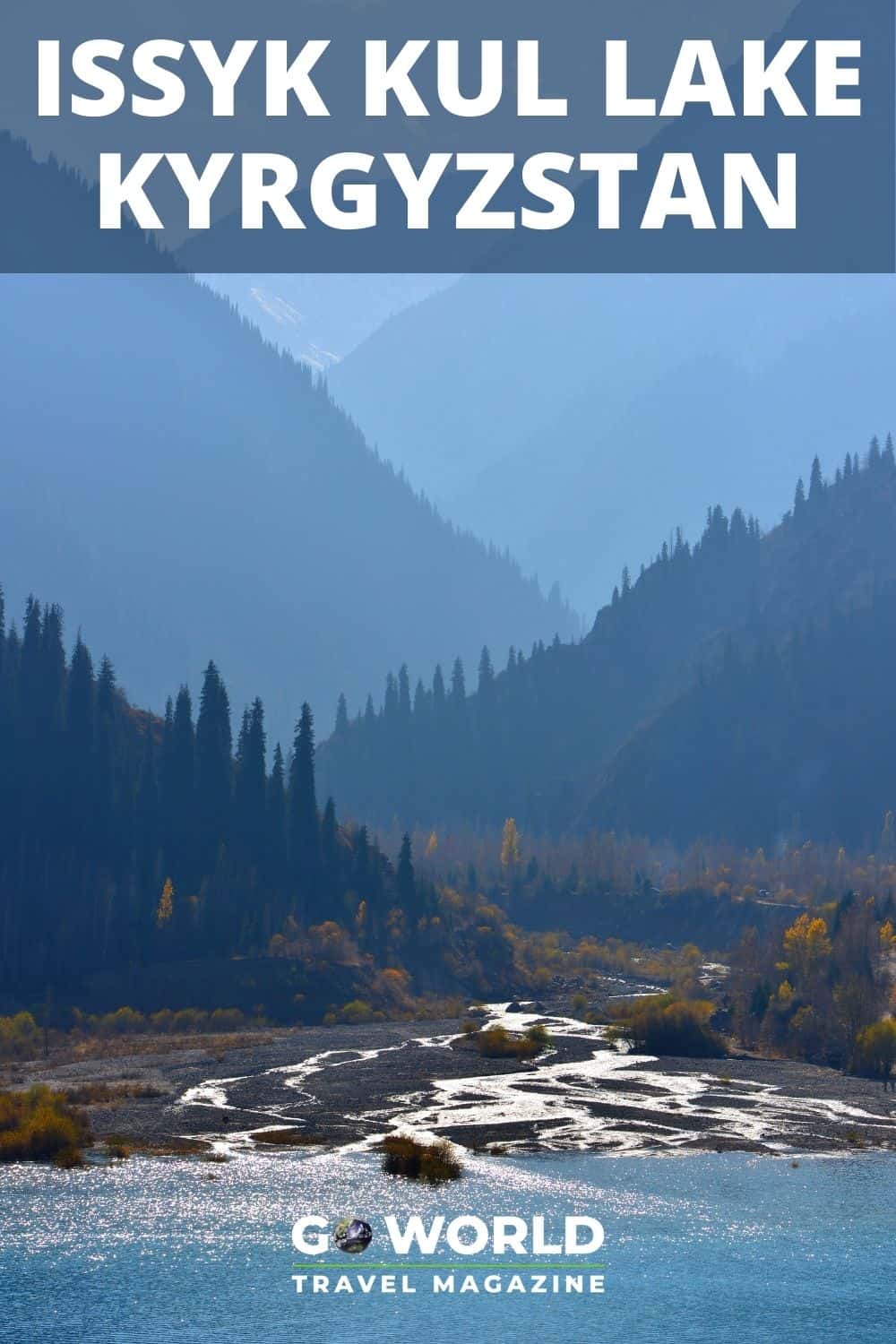

A View of Issyk Kul Lake

We jumped out at the final fork in the road and made our way up the last 1.2 km. It was a steep uphill climb, passing a farm along the way with muddy tractors and splinter-filled fences.

We gestured, indicating walking people with two fingers. Two older men in torn jeans and off-white buttoned-down shirts waved us through with a grunt.

Two yurt camps lay untouched, due to pandemic-era low tourist numbers, no doubt. At the highest point in the ridge, around a bend and past a brush, we finally emerged to a panoramic view of the lake’s southern coast. The next smallest town, Tong, lay on the left with multiple lake-side camps lining the shore down the right.

The preparations for the upcoming second annual Kol-fest, an international music festival, were well underway. Scaffolding and trucks could be seen all along the shore.

Further inland, the lights and tops of homes from Bokonbaeva were the largest blocks in view. The lake’s pristine blue water spread out in front of us, without any visible sign of the opposite shore.

Bel-Tam Beach Yurt Camp

We had all booked at the same Bel-Tam beach yurt camp for that evening so we shared a taxi there. The camp had about 15 yurts. Some of which could fit up to 4 mattresses on top of multiple layers of wool carpets on the ground. They were sturdily built to protect from the chill of the lake that was just 20 meters away.

A large dining yurt had multiple tables and numerous cushions on the floor. We enjoyed a home-cooked traditional meal there with other visitors from around the world. As we ate we shared stories of the horse riding adventures and hiking trails we’d visited that day.

Eventually, people began to drift off towards the bar by the open kitchen. Their laughter carried out over to where others sat around a bonfire, stargazing and breathing in the salty lake breeze.

I found myself by the hand-crafted swings with some of the young local staff. Many were high school students working during their summer holiday and hoping to practice their English.

They regaled me with stories about the last Kol-fest. “All the major singers came from all over the world, nobody sleep for days!” I also heard of all the work going into this year’s doubly grand event to compensate for the 2020 canceled festival.

When I retreated to my yurt for the evening, I found it to be pleasantly insulated. Not just from the cold but also from noise. The colorful interior matched the folktale written inside on parchment. It detailed the history of the previous owners, a nomadic family of 8.

A heavily padded mat rolled down to cover the entrance. The circular ring at the top, a family heirloom that gets passed down as an essential component for keeping any yurt intact, let in just enough light to see the night sky.

Kayaking on Issyk Kul Lake

The next morning, I was picked up for my kayaking adventures with Nastyia and Sergey, two Russians that were the tour guides for our group of 7. After a brief introduction to basic safety tips, we launched into the water.

We were two people per kayak, with life vests on and pouches of snacks, safely in plastic bags, for our break.

I was partnered with Nastyia, who pointed out the various rivers that merge into the lake with freezing glacial run-off water. I chuckled at her description of the decades-old “iron giraffes” which take goods, such as coal and wood, from ships and deliver them across the lake.

At one point, we passed a dock with a structure on it.

Nastyia mentioned it was for “pushing turpek” back in the Soviet days. When I asked what that was in English, she struggled to explain. It took 10 minutes of dancing around the elusive word before we discovered that she meant testing torpedoes in the height of the USSR.

At our lunch break, on the sandy beaches of the north shore, we spoke about the lack of water activities on the lake except for theirs and the potential for tourism and marketing there. They elaborated on their history of launching the kayaking business.

It was created with assistance, training and donations from the German development organization GIZ. Also, they had primarily developed it to provide for their NGO that ran leadership and language workshops for youth.

Meeting a Yurt Maker and His Family

After rowing back towards our launching point, we were dropped off in town where a friend met me with her rental car. She planned to meet a local yurt-maker to negotiate prices for shipping back to the U.S. and wanted some company.

With the man’s address in hand, we headed towards a small town called Barskoon. We pulled up to a large yard with an open gate and knocked on the main door.

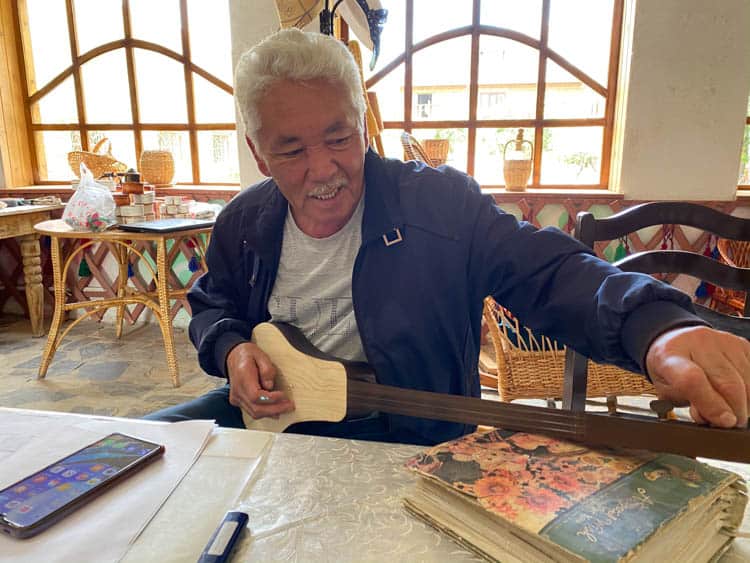

An elderly man, the yurt-maker named Mekenbek, welcomed us into his home and business, called Ak Orgo, along with his wife and 11-year-old daughter. The main entrance was clearly their living room. Hand-made wool crafts were all over the walls and on tables with stickers displaying the prices.

Mekenbek’s daughter stood by him, fingers furiously Google translating as he discussed prices and details with my friend. The cost was dependant on the size – 3 meters in length, 5 meters or 10 meters for large events – and the type of detail in the reeds which encircle the yurt.

The mother kept supplying the table with borsok, a triangular fried dough commonly eaten with jam and tea. Together, they were an adorably comical group. Mekenbek showed us photo albums of his artisanal crafts fair exhibition in the U.S. two decades ago.

His daughter chirped up once in a while from behind him with occasionally mistranslated words. His wife also popped in and out of the kitchen, only to reappear with a cup of sugar or bananas, eager to please her foreign guests.

During all this, she even convinced Mekenbek to play his komuz, a traditional string instrument that he happened to have hanging on the wall.

Making New Friends

Afterward, they took us on a tour of his workshop in the adjacent building. The first few rooms had a myriad of machinery covered in layers of wood chippings and dust.

Some were mechanized ways of pounding wool into the carpet. Others helped to shave off the rough layers of wood for the ring to encircle the bottom of the yurt.

A large room to the side held patterns for spray painting designs, and the largest room of them all held multiple pieces of curved planks which could be folded so the yurt could be transported.

An enormous outdoor space was open around a series of concentric circles, obviously used to erect and work on differently sized yurts.

By the time we left, Whatsapp numbers were exchanged and stored in our phones, the girl was confident enough to string together whole phrases in English and the mother gave us some pastries to go. We waved farewell to Mekenbek and his family, the melody from the komuz still playing in our memories.

Book This Trip

Start planning your trip to Kyrgyzstan today. Get prepared with insider tips on how to get around, hotel and VRBO accommodations, restaurant recommendations and more through TripAdvisor and Travelocity.

For the best flight options, train tickets and ground transportation in Kyrgyzstan check out OMIO Travel Partner.

After Kyrgyz, which is a Turkish language, Russian is the lingua franca. It will help if you can at least learn to read some Cyrillic, if not learn the basic phrases in Russian or Kyrgyz. Knowing some Turkish will also help in communicating with locals.

Download Maps.Me which has many hiking trails. Check the weather and pack accordingly – the summers around the lake don’t get much warmer than 25 in the daytime.

The Bel-Tam Beach Yurt Camps can make reservations in advance, although it’s not necessary. They can be reached at +996 555 922 919. They are also a part of a group of yurt camps with many other locations, depending on your preference.

Author Bio: Annie Elle is an international educator who has lived and worked abroad for the last 10 years. Originally from Los Angeles, she is currently living in the Kurdistan region. She has recently picked up ultimate frisbee and continues to passionately seek out new foods to try in her spare time.

- A Stay at Estancia Cerro Guido Will Enrich Your Patagonia Experience - April 30, 2024

- 12 Cool Things to Do in Tbilisi, Georgia’s Vibrant Capital - April 29, 2024

- Travel Guide to Spain - April 28, 2024