In Bangkok, forget or temporarily suspend the Western notion that the main function of sidewalks is for the movement of pedestrians. The facilitation of pedestrian traffic is one purpose, but it’s certainly not the priority.

In Bangkok, forget or temporarily suspend the Western notion that the main function of sidewalks is for the movement of pedestrians. The facilitation of pedestrian traffic is one purpose, but it’s certainly not the priority.

The narrow, crowded sidewalks also host a litany of alternative functions: food and clothing stalls, motorcycle taxi cues, telephone polls and booths, and grounds for fortune tellers, beggars and solicitors. Ironically, sometimes it is easier to walk on the traffic-choked streets than the sidewalks.

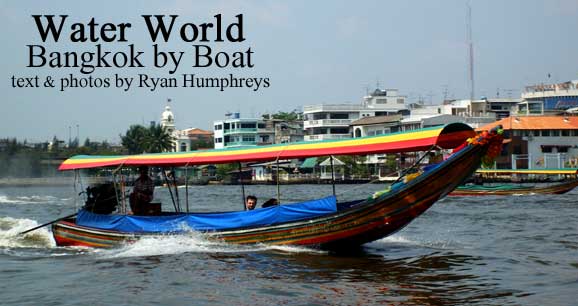

The frustrating obstructions, the oppressive heat and the relentless entrepreneurial salespeople can make exploring Bangkok on foot an aggravating experience. So where is all this leading, you ask? To the water, fellow traveler. If you are looking for a calmer, gentler, more traditional Bangkok, you might consider leaving the frenzied streets altogether and exploring it by boat.

As we glided peacefully down the canal, Joop, the captain, brought me out of my Huckleberry Finn–like daydream.

“To the front of the boat, to the front of the boat,” she called, gesturing vigorously, as we approached a low bridge.

I scrambled out of the seat next to her and rolled across the cushions toward the bow.

Another tourist group, approaching from the opposite direction, seemed to be involved in similar somersaults, moving to balance the boat’s weight.

We narrowly slipped under the bridge and, with a sigh of relief, Joop brought me deeper into the heart of her canal community.

The canal communities in Bangkok’s Thonburi District hug and spill into the cloudy brown water. I could easily have jumped onto shore and, if feeling particularly bold, joined numerous families for lunch, saved a penalty kick, joined a group of elderly men for a game of mahjong, helped a monk turn off a faucet or leaped, uninvited, into a wedding. Everything was open and within arm’s reach.

The children, with toothy, ivory-white smiles, were the most delightful surprise of the trip. A few feet from our boat they teetered fearlessly on pipes before back flipping into the water. They were everywhere along the canals: small brown heads bobbing like buoys in the dirty, coffee-colored stream.

One daring little rascal, naked, his skin a similar hue to the murky water, grabbed the rail of our boat and let it carry him along, shrieking and laughing before letting go. The boys were all over the place, but where were the girls? I asked Joop.

“Girls not allowed in the canals.”

“Why?”

She thought for a moment and dropped her ever-present smile. “Too dangerous,” she said, and as if reaching an epiphany, added, “and too dirty.”

There were several tourist boats like mine noisily chugging through the canals. The apparent ease with which the residents politely accepted legions of us into their lives was impressive and a little unexpected. Families eating, washing, playing, dressing and sleeping were in naked view. Did they mind? No, apparently not. But surely this complete absence of privacy must have bothered them, or was I viewing matters through a Western lens?

“No it doesn’t bother us,” Joop said, smiling at my suggestion.

“Since I was a young girl, foreigners visited these canals. If not for you, the government would fill them in and build roads.”

In the 19th century Bangkok really was a floating city, and deserved its title as Venice of the East. Four-hundred-thousand inhabitants lived in floating houses on the river, and the rest lived in amphibious habitats — houses on stilts on river or canal banks. The river was the community.

Beginning in the mid 19th century, King Mongkut (Rama IV), and then his son King Chulalongkorn (Rama V), pursued a policy of modernization, and roads and railways were built on and beside the canals.

In their blind, perhaps reckless, race to keep pace with the developed world, Bangkok’s unique aquatic communities were displaced, paved and replaced with roads and car parks.

We passed the Taling Chan Floating Market and saw wizened old women in dugout canoes selling food — chicken, pork, eggs and spices — to locals bunched together on barges. Farther on, past the market, old crumbling temples poked out from fleeting pockets of brush. Shortly after the market we left the canal and joined a wider channel, a tributary of Bangkok’s main river, the Chao Phraya.

Shirtless fishermen lined the shores, casting with their homemade rods into the calm waters under stilted buildings. In the middle of the river, water buses, tourist boats, barges and tug boats passed dangerously close to each other.

In the midst of this crowded marine traffic, a hunched figure in a dazzling purple frock paddled with swiftness and dexterity from the shore to our boat.

When this brave character reached us, I expected to view the countenance of a lean, chiseled rower. Instead, it was a happy, chatty granny named Dow who had been chasing tourist boats for more than 20 years.

Her canoe was heavily laden with cold beer and trinkets. I bought a cold Singha beer and five golden elephant key chains. Before she pushed off, I asked her if there were any difficulties in her profession: large waves, water snakes, too many vessels on the water?

“Ice!” She quickly replied, and pushed off to chase a long, sleek cruiser bursting with tourists.

Bangkok is an evolving city of contrasts — a dizzy, seething mixture of old and new, opulence and poverty, temples and mosques, markets and malls. The city’s industrious canal communities showcase a slower, more traditional lifestyle. The lives of these inhabitants, basic and authentic, are displayed along these narrow waterways. Go ahead, pass through their living room — they don’t mind — honestly.

If You Go

Take the skytrain to the last station (Saphan Taksin) on the Silom line and walk directly under the station to the pier. At the pier, staff at booths sell canal and river tours.

Alternatively, about 5 minutes walk northeast from Khao San Road, the pubic boats stop at the Tha Phra Athit River express pier, in the Banglamphu District. It is located on Ratchadamnoen Road under a low bridge, not far from Wat Ratchanada, Wat Saket or Democracy Monument.

You can book a seat on a group tour, hire your own boat or join the students, office workers and monks on the public boats. Expect to pay between 500-1,000 baht to charter a longtail boat for one hour.

There is no set price, and you can negotiate with the operators. It is polite to tip the boat operators, and it’s appreciated, since the bulk of their earnings come from your charity.

The average fare on the public express boats and canal boats is 5-10 baht, depending on distance.

Thailand River and Canal Tripswww.thailand.com/travel

Thailand Tourism

www.TourismThailand.org