Franz Kafka once described his native city of Prague as being a dear little mother with claws who never let him go. Throughout his life he had a love-hate relationship with the city, always wanting to go but never seeming able to escape. Ironically, now, many years after his death, Kafka’s entrapment in Prague is greater than ever.

Franz Kafka once described his native city of Prague as being a dear little mother with claws who never let him go. Throughout his life he had a love-hate relationship with the city, always wanting to go but never seeming able to escape. Ironically, now, many years after his death, Kafka’s entrapment in Prague is greater than ever.

Declaring itself the “City of Kafka”, Prague has associated itself with the brooding iconic face of Franz Kafka. Gift shop shelves are cluttered with Kafka mugs, Kafka books and screen-printed Kafka t-shirts. There is a Kafka memorial near the Old-New Synagogue, a Kafka Café pub and a Kafka bust standing guard in the Mercure Hotel’s lobby, located in the office Kafka once worked at as an attorney.

With a newly opened museum chronicling the writer’s prolific and tormented life, Kafka is now forever trapped in the “bird cage” of Prague.

“I think he would hate it,” laughs Dr. Marketa Malisova, director of the Franz Kafka Society, when asked what Kafka would think of his celebrity status. “He never thought he was a good writer,” Malisova says, reiterating Kafka’s dying wish for all his works to be burned.

“He was an attorney first and a writer by night. During his lifetime, Franz Kafka was known as a great attorney. He did not become known as a writer until well after his death.”

But how did Kafka go from being a successful attorney with a writing hobby to becoming the literary icon of Prague? “During communist times, Kafka was forbidden,” says Malisova. “After the fall of communism, as Prague looked to morph its image into something new, Franz Kafka offered a piece of Czech culture that Prague could hold out to the world and say, ‘This is us’.” Thus, The City of K, a postmodern exhibition, was born.

Whether he would love it or loathe it, the ghost of Kafka has a presence felt at all levels of the city. Beyond the knick-knacks filling souvenir shops, Kafka has successfully, albeit unintentionally, shaped Prague.

There are the cultural events organized by the Franz Kafka Society, a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving both the literary genius of Kafka and also promoting and supporting aspiring writers and artists.

The Franz Kafka society is responsible for operating a Kafka library, featuring both his canon of works and a variety of literary criticism, along with creating the hauntingly abstract Franz Kafka memorial.

The haunts of Kafka’s lifetime speckle the city’s main attractions. Tracing his footsteps through the city gives the traveler a thorough tour of Prague. Even Kafka himself once seemingly foretold of this, stating that if one drew a circle around a map of Old Town, “That narrow circle encompasses my entire life.”

Start at Namesti Republiky and stroll up the tram-jammed Na Porici to the former office building of the Worker’s Accident Insurance Company of the Kingdom of Bohemia. Now home to the Mercure Hotel, it is here that Kafka spent his working days as an insurance attorney.

From work, chase the ghost of Kafka toward home. Continue down Na Porici, wind around the intensely muraled Municipal House and pass the imposing Powder Tower before merging onto Celetna and on to Old Town Square, the heart of both Prague and much of Kafka’s life.

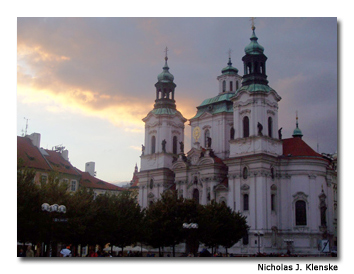

Kafka described this cobble-stoned square as being the equivalent of his front yard. At different points in his life, he lived and worked in various homes scattered around the premises of this legendary square containing such cultural icons as the gothic Old Town Hall and baroque St. Nicholas Church.

Addresses 3 and 2 can be found as Celetna Street opens to the hustle of the square and its plethora of cafes. It was inside these present-day souvenir shops, many selling memorabilia of their former patron, that Kafka lived with his family and penned his first story.

Farther into the square is the Unicorn Apothecary building, identified by the unicorn adorning its façade. It was here that Berta Fanta hosted an intellectual salon, where such great minds as Kafka, Max Brod, Franz Werfel and Albert Einstein once held court.

Within the square itself are a handful of former Kafka homes. Near the domed St. Nicholas Church, in the surprisingly quiet U Radnice Square, is building number five, Kafka’s birthplace in 1883. Crossing the square to the far side of the Town Hall’s astronomical clock is a distinct building covered in a black and white fresco depicting scenes from Greek mythology. A young Kafka lived here from 1889 to 1896.

The stone building snuggled into the shadows of Tyn Church’s dual towers, sharing a corner with a Kafka bookshop, is where Kafka took refuge during World War I.

Not only is Kafka unique in his writing style, he was also unique in his own cultural composition. He represented a small cultural faction of the Prague intellectual scene of the early-20th century, as he was Czech, spoke and wrote German, and was Jewish. Thus, Kafka’s trail undoubtedly leads to Prague’s Jewish quarter and the old Jewish ghetto.

From several blocks away, the jagged, pyramid roof of the Alt-Neu Synagogue cuts through the gray sky. With a history that includes hundreds of Jews being herded inside only to be slaughtered, it is unquestionable that Kafka, who attended services here, was influenced by these horror stories. Down the road from the synagogue is the Old Jewish Cemetery, where approximately 12,000 bodies, buried 12 deep, cause the earth to swell like the waves of a sea.

Across the gothic statue lined Charles Bridge and up into the expansive Prague Castle is the pedestrian Golden Lane. Although now various gift shops and other tourist attractions occupy the building, Kafka once called number 22 home.

Head down the steep Old Castle Stairs to the bottom of Castle Hill and the newly opened Franz Kafka Museum. Guarded by a ghostly, abstract sculpture of two men urinating into a pond, this comprehensive museum does an excellent job of capturing both the facts of Kafka’s biography and the creative genius that occupied his mind.

Along with rare copies of Kafka’s letters and books, the museum also has displays focusing on his major works.

Exit the museum and come face to face with a giant black K. Despite the fact that during his life Kafka only thought of escaping, today there is no escape. Franz Kafka permeates Prague, defining both what it was and who it has become.

Nothing summarizes this shared history better than the poignantly simple, yet somehow complex, letter “K.”

If You Go

Prague Tourism Bureau

www.prague-info.cz

Franz Kafka Society

www.franzkafka-soc.cz

Franz Kafka Museum

Open daily 10 am to 6 pm.

www.kafkamuseum.cz

Nicholas J. Klenske is a freelance writer living in Brussels, Belgium. His work has appeared in The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, New Haven Advocate and Eons.com. Contact him through www.KlenskeInk.com.