The Philadelphia skies are heavy with wintry clouds and the changed leaves of the trees near Independence Square have fallen to the ground. Through the carpet of yellow and brown, boots plod past on the cobblestone streets. The wind seems not to stop, and passersby hide beneath the shelter of thick scarves and wool pea coats.

The Philadelphia skies are heavy with wintry clouds and the changed leaves of the trees near Independence Square have fallen to the ground. Through the carpet of yellow and brown, boots plod past on the cobblestone streets. The wind seems not to stop, and passersby hide beneath the shelter of thick scarves and wool pea coats.

Cool stone benches dot the edges of the Old St. Paul’s Episcopal Church graveyard, a colonial cemetery in the heart of Old City, Philadelphia. The people lie quietly now, with not much more than grave markers to tell the stories of their past.

Much of the United States that we know today began in Philadelphia. Long before the colonists’ 1776 declaration of independence from Britain, this Pennsylvania town was designed and developed by William Penn, in 1682. This was the birthplace of the United States’ earliest public parks, its first volunteer fire association and its first hospital. And from 1780 to 1900 it served as the nation’s capital.

Philadelphia was the hub of events leading up to the American Revolution, and thus a magnet for influential people. Many of them — including scientist and diplomat Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), American astronomer and first director of the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia, David Rittenhouse (1732-1796) — found Philadelphia to be their final resting place.Philadelphia cemeteries, found throughout the city, offer a unique way to discover American colonial history.

Old City/Society Hill

Beginning downtown, on Third Street, and walking south from Market, visitors can take a self-guided tour of four colonial cemeteries. Between Walnut and Locust Streets, a small iron gate swings open to a short path alongside Old St. Paul’s Church. No longer used as a church, it serves as headquarters for the Episcopal Community Services of the Diocese of Pennsylvania. In contrast to the red brick of the restored church, whitewashed gravestones line the sidewalk.

Though small, the cemetery at Old St. Paul’s holds 11 revolutionaries, from doctors and patriots, to captains and soldiers. Visitors can pass the family vault of Philadelphian George Glentworth, who was buried here in 1792. Glentworth graduated from the University of Edinburgh in 1758, and served as a senior surgeon in the American Revolution.

Glentworth’s son, Plunket Fleeson Glentworth, was also interred at Old St. Paul’s. America’s first president, George Washington, was attended by the younger Glentworth while the president was in Philadelphia.

Fleeson became a fellow of Philadelphia’s College of Physicians, which has a museum dedicated to educating future doctors. Today the Mütter Museum is visited by curious locals and visitors, who stop by to view the Fear Factor–style displays of preserved anatomical specimens and medical abnormalities.

South of Old St. Paul’s, near the corner of Third and Pine streets, is St. Peter’s Church, with its tall spire. This National Historic Landmark continues today as a house of worship. The ministry maintains the site’s crowded colonial cemetery.

Enclosed by iron gates and short brick walls, the worn tombstones stand cluttered together like tiny soldiers; more than a century of weathering has rendered many inscriptions unreadable. It’s surprising to find such calm near the pub-driven tourist district of South Street. But the people interred in this now-quiet churchyard were not so reserved during their lives.

George Mifflin Dallas (1792-1864), for whom the Texas city is named, held high ambitions for political fame. He rose from mayor to district attorney, state senator to U.S. vice president under James Polk.

With hopes of a presidential future, Dallas made a career-ending mistake by abandoning his constituency on the issue of tariffs. In addition, Dallas’ unflinching stance on heavy national issues assured his eventual demise.

Across the churchyard from Dallas lies American portrait painter Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827). An eager patriot, Peale moved to Philadelphia to join in the American Revolution as a captain of volunteers, painting military leaders whenever he had the opportunity. The earliest-known painting of George Washington is believed to be by Peale.

White settlement in the Americas wrought the distressing reality of new diseases that immigrants brought with them, which took the lives of countless Native Americans. Eight Native American chiefs contracted smallpox while visiting Philadelphia to meet with the country’s first president. St. Peter’s churchyard was their final stop.

One block away, at Fourth and Pine streets, an archway covered in green ivy marks one of several entrances to the cemetery at Old Pine Street Presbyterian Church. Like the other two churchyards, Old Pine Street is a tight colonial cemetery.

American patriot George Duffield was the first pastor of Old Pine Street Church, which was built in the 1770s. Duffield used his position in the church to fight the same war he would wage on the battlefield: the battle for American independence. His stance drew nearly 60 parishioners into battle.

In 1777, British troops occupied Philadelphia and gutted the church building, turning it into a makeshift hospital. Pews were burned to warm the sick and, later, the church became a stable. The cemetery yard was also desecrated, but, one block away, Old St. Peter’ s remained a house of worship.

Today, the churchyard is lined with leaning gravestones that mark the burial sites of revolutionary war soldiers, captains and colonels. Interred is the namesake for Philadelphia’s ritzy Rittenhouse Square neighborhood, David Rittenhouse. Mathematician, astronomer and inventor, he helped build one of the first telescopes used in the United States. The former conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra for 42 years, Eugene Ormandy (1899-1985), is also buried here.

About six blocks north, in the Christ Church burial ground, at Fifth and Arch streets, lies Philadelphias better-known inventor, and its most famous resident, Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790). As a scientist, Franklin made major contributions to the theory of electricity. Most notable was his experiment of flying a kite during a thunderstorm, which proved that lightning is an electrical discharge.

In addition to being a scientist, Franklin was an inventor, printer, civic activist and diplomat. A member of the committee that drafted the Declaration of Independence, Franklin has also been credited with inventing the idea of an American nation.

His name appears across the city, with a major bridge, busy parkway and an interactive science museum, the Franklin Institute Science Museum, all bearing his name. A huge sculpture near Fifth and Market streets honors his kite experiment, and even on a short trip through the city, it’s easy to see that Franklin is Philadelphia’s poster boy. When Franklin died, an estimated 20,000 mourners — philosophers, physicians, politicians and regular citizens — attended his funeral.

The two acres (about 8,000 m²) and 1,300 markers of Christ Church burial ground are surrounded by high brick walls. A simple marble stone marks the resting place of Franklin and his wife, Deborah. When the sun shines, the marker flashes with the reflection of a few scattered pennies, the smallest of American coins. Good luck is said to bless the coin-tosser.

For 25 years the cemetery was closed to the public, but the grounds were reopened for good in May 2003 in preparation for the city’s 2006 year-long celebration of Franklin’s 300th birthday.

Through December 2006, a historian-guided tour starts at the Franklin gravestone and continues on to the grave markers of his family, friends and foes. The tour is included in the price of the grounds entry fee, US $2 for adults, US $1 for students and US $10 for groups of any size.

Laurel Hill Cemetery

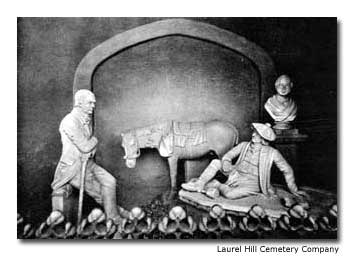

A few miles north and west of Philadelphia’s downtown district, tombstones spread like ripples on water across the rolling expanse of Laurel Hill Cemetery . Laurel Hill’s 78 acres (.3 km²) and thousands of tombs were designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1998.

Beyond the iron entrance gates, narrow roads snake through a landscape of simple sandstone markers, towering granite obelisks and carefully carved marble sculptures. Tightly grouped columns and pointed arches mark many of the grand mausoleums. Atop one vault an angel gazes skyward; beside her Jesus bears a cross. Buried here are rich Philadelphia families and Civil War generals, some graves marked with tiny American flags.

Laurel Hill was designed by Scottish-American architect John Notman and founded in 1836. The cemetery’s park-like grounds were a popular attraction in the 1840s. Its popularity helped inspire a national movement toward green spaces in urban areas.

On the west side of the grounds, terraces are cut into a bluff. More mausoleums, some the size of miniature houses, overlook a section of the 128-mile-long (206 km) Schuylkill River . (Philadelphia’s first developer chose the city’s location based on the confluence of the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers.)

Follow the curved steps down cemetery terraces or walk the narrow paths between crumbling colonial gravestones; the memory of Philadelphia’s historical heavyweights survives well beyond the depths of dusty books.

If You Go

While the cemeteries in the Old City and Society Hill neighborhoods are great for a walking tour, Laurel Hill Cemetery is best reached by car. For maps and travel information visit the official Website for the Greater Philadelphia area: www.gophila.com

Old Pine Street Presbyterian Church

www.oldpine.org/opstory.html

Historic Christ Church and Burial Ground

www.oldchristchurch.org

Laurel Hill Cemetery

www.thelaurelhillcemetery.org

Mütter Museum, College of Physicians of Philadelphia

www.collphyphil.org/mutter.asp

For more information on additional cemeteries in the Philadelphia area, visit www.phillygraves.com.

- Why the Kimberley Should Be Your Next Australian Adventure - July 5, 2025

- How We Finally Afforded Our Dream Trip to the Swiss Alps (And You Can Too) - July 5, 2025

- Escape Manhattan for Governors Island - July 5, 2025