The petite, raven-haired women in shimmery rainbow-colored pleated skirts swirled off the launch carrying bundles and bags, and then disappeared up Escheresque stairs that climbed the steep hillside wherever I looked.

I scurried to follow. I was intrigued by these living symbols of folk tradition who still wore the finely embroidered blouses and silken skirts of their ancestors as they went about their daily routines. But the Purépechan Indian women seemed to evaporate like a fading rainbow into a rabbit warren of stairstep shops, rooftop terraces and crooked alleyways.

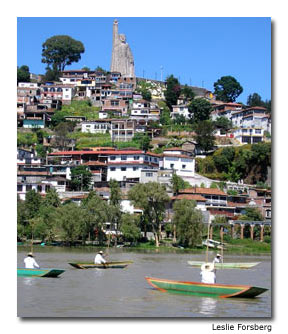

My husband, Eric, and I were visiting Janitzio, a tiny, gumdrop-shaped island on 15-mile-long Lake Pátzcuaro, tucked into volcanic mountains in Mexico’s Michoacán state. The houses, churches and other buildings on the island seemed squeezed as if by a giant grip, pressing skyward. We had approached Janitzio on a long, wooden, canopied boat filled with three dozen passengers — Purépechan Indians returning from their marketing chores in the lakeside town of Pátzcuaro and a few Mexican tourists.

As we skimmed over the shallow, silty lake toward the island, a statue of José María Morelos, a Mexican revolutionary, grew to giant proportions atop the island, raising his fist skyward.

Just off the island, fishermen in dinghies stood up and dipped immense butterfly nets into the water for the entertainment of the boat’s passengers, then passed baskets for collections.

A young brother and sister on our boat beamed as they playfully dipped their tourist-trinket reed nets into the water, mimicking the fishermen’s motions. This style of fishing has been done here for generations. The catch,pescado blanco (white fish), is the centerpiece of the local cuisine.

We disembarked in a plaza and worked our way up well-worn stone steps, passing modest stucco homes; a cemetery where the graves were adorned with marigolds and candle stubs; and a middle school recreation yard buzzing with plaid-uniformed students on recess. A small stone church tucked into the hillside was a welcome break from the heat of the day.

Inside the dim space, women kneeled before an immense altar with a painted statue of Jesus, arms outstretched. Overhead, fishing nets filled with masses of brilliant yellow marigolds hung from the ceiling. Marigolds have held ceremonial significance in the Lake Pátzcuaro region since pre-Hispanic times.

There were no marigolds at the apex of the island, but a profusion of roses and other flowers, in a tidy formal garden surrounding the base of the Morales statue. Inside the statue, a circular staircase wraps ever tighter and narrower, like the inside of a nautilus shell, to the summit of the statue.

Just one floor up, Eric paused to examine one of a series of vivid historical murals of Morelos’ life that lined the stairs then he stared balefully upward at the steep stairs. I knew Eric was acrophobic, so I tossed down the gauntlet: “Come on! It’ll be OK!” I said, as I retraced my steps from the next level up. “No, I’ll stay right here, Eric said, emphatically. “Come on, if I can do it you can,” I urged. Farther up, I leaned over the railing to look down the spiral. “Oooh, it’s just black below … don’t look down!”

Step by step, holding hands in the narrow parts, we crept upward 150 feet (46 m) until we emerged from the stuffy, tomblike interior to an observation platform teased by a fresh breeze. Eric sported a wide grin as he surveyed the scenery.

The lake spread before us to nearby islands, distant green hills that looked like rumpled velvet and farm fields. To the south, we could make out the patch of buildings on the forested slope that is Pátzcuaro, one of the loveliest towns in Mexico, and the place where we were staying.

This high mountain town of 45,000 is surrounded by pine forests and lush tropical vegetation in an area where the volcanic soil and moist heat of the day create a jungle-like profusion. The town’s two plazas are shaded by immense elm trees that form a canopy over the adobe buildings with red tile roofs. Red-and-black signs, all using the same style of writing, identify each business.

Purépechans (called Tarascans by the Spaniards) settled in the Pátzcuaro area in 1324. Pátzcuaro was the most important religious site for the Purépechan kings, who believed that the region was the gateway to heaven. In addition to being religious, the Purépechans were accomplished warriors. They were the only indigenous people who managed to keep the Aztec empire from expanding into their area. Thus, the Purépechans developed their own unique culture.

We had arrived in Pátzcuaro in the evening, and settled into La Mansión de los Sueños, (House of Dreams), a lovely boutique hotel in a restored 17th century home, with hand-carved furniture, folk art and a fireplace in each room. It was dinnertime, and we explored the profusion of cafes lining the cobbled streets around the central square, Plaza Vasco de Quiroga.

We chose a charming restaurant, El Primero Piso, (The First Floor) and were lucky to score a table on a private balcony. We dined on fried pescado blanco served with an almond sauce, and a delicious Tarascan bean soup, aromatic with chiles and with a dollop of soft white cheese on top. That was it … we had to have the recipe, and decided to search for the ingredients needed to make this extraordinary soup.

In the morning, we set off to explore. Following a small tide of people, we turned a corner and wandered into the town’s Friday market. We waded into the bustling crowd of shoulder-high Purépechans shopping, and others selling their local harvest or catch at rustic wooden stalls or just out of baskets lined up in the church square. A hum of conversation swirled around us as diminutive grandmas in gingham aprons and shawls, hair wrapped in cloth, pushed past, carrying bundles and crates.

At one wooden stall, a bubbling cauldron of fish soup served in brown pottery bowls was breakfast for a dozen locals. Moms greeted friends streaming into the market, while toddlers and children played nearby. Woven baskets of tiny dried silvery fish took up an entire section. Ten-inch-long (25 cm) fish lined up on newspapers were still gasping. “That’s how buyers tell they’re fresh,” Eric joked.

Papayas, oranges and lemons were stacked high in the fruit section. Nearer the church door, used clothing was heaped in piles on the cobblestones. Back toward the street, permanent market stalls catered to those in need of embroidered blouses, a shave or hardware. Three little girls in pink and orange dresses played ring-around-the-rosy in the center of the sidewalk. They flashed shy, curious smiles as we edged past.

Beyond the girls, a kind-eyed woman in a checkered apron beckoned to us. She gestured to a pile of fruit that looked somewhat like apricots. “Que es?” I asked. “Misperos,” she replied. She chose one and offered it for a taste. It had a sweet, tropical flavor, vaguely familiar, yet unknown to our palates. We bought a small bag of them to enjoy on our walk.

Rounding a corner, we came across a bean shop where dozens of varieties of beans were displayed next to numerous dried chiles. We asked the merchant how to make Tarascan soup, and she measured out yellow beans and smoky black chiles, then offered to write the recipe down for us. Eric and I were exuberant, thinking of rainy days to come at home with fragrant Tarascan soup bubbling in the kitchen.

Leaving the market behind, we strolled to Plaza Vasco de Quiroga to shop for some of the local crafts. When Spanish bishop Don Vasco de Quiroga was sent to Pátzcuaro in 1536, he decided to help improve the economy of the Purépechans.

He did this by encouraging the people living in traditional villages around Lake Pátzcuaro to develop unique crafts that they could use for trading. This early business venture blossomed, and today the region is well-known for its traditional crafts: Hand-painted pottery, copper plates, woven tablecloths, silver jewelry and straw ornaments.

In El Mesón Galeria, gorgeous pottery pumpkins in green, gold and brown hues with whimsically curly vines caught my interest. They were displayed next to heavy glassware with cobalt blue rims, and wooden religious icons. Painted tin decorations — hearts, crosses and other symbols — made up a kaleidoscope-bright display on one wall.

When we had our fill of shopping, we stopped at a sidewalk ice cream shop beneath one of the square’s arcades. A sign said “Since 1905.” Ice cream is one of Pátzcuaro’s specialties. Deep metal cans with lids were nested in burlap and ice. I tried mango ice cream, while Eric had piñon (pine nut) and peach-colored mamey, (a tropical fruit). We settled onto a bench in the square and watched children playing in the fountain and boys showing off their bike tricks.

An evening concert in the courtyard of the Jesuit College brought out a blend of locals, from well-coifed women in pant suits to moms in shawls and voluminous skirts, toddlers on their laps. As day settled into evening, bats flew overhead and Grupo Gaban, five Morelia musicians in serapes, played festive music from throughout Mexico on violins, guitars, a clarinet and a harp.

Dinner, after, was at the market. Pools of light at food stalls lit up the darkness. A potato chip maker plunged whole, spiral-cut potatoes into hot oil and served them to us still warm and crunchy, with chile sauce and lime juice.

Nearby, at El Pollito Feliz (The Happy Little Chick) we squeezed onto benches next to students, and listened to the cozy hubbub of conversations over the roar of the gas-fired stove and the bubbling sounds of our dinner — a huge platter of fried chicken, served with a mountain of sautéed carrots and potatoes in a mild chile sauce.

Two bright-eyed little girls in braids and ruffly party dresses played hide-and-seek, families relaxed and chatted after a day’s work, and Eric and I sat among them, ruminating about the vividness of life here and feeling very much a part of this inviting, beautiful place.

If You Go

Pátzcuaro Tourist Guide

www.mexperience.com/guide/colonial/patzcuaro.htm

Mexico Tourism Board

La Mansión de Los Sueños

www.prismas.com.mx