Myanmar (formerly Burma), wedged between China, India, Laos, Thailand and Bangladesh, feels like a land lost in time. It is a medieval country of golden towers and ancient stone temples on hilltops.

The expansive plains of Bagan, in the country’s dry center, were once studded with more than 6,000 of them in an area of only about 15 square miles (40 km²). About 2,000 pagodas still exist today — some meticulously maintained, many crumbling back into the earth. This hazy savannah of closely packed pagodas stretches to the horizon, and feels like a scene from a movie epic. Many, originally built to house nat, orspirit deities, are more than one millennia old.

From Bagan it’s a 10-hour journey into the mountainous Shan Plateau in the Shan State of eastern Myanmar. Road travel is slow around Myanmar, and some major routes are often closed to foreigners by the ruling military junta.

Along with my fellow band of travelers, I chugged along in an archaic bus past horse-drawn carts, trails of orange-robed monks, and town people whose faces were smeared with beige paste, their lips blood-red from chewing betel nut. Out in the wilderness, a gang of “involuntary” laborers stopped digging just to wave at us enthusiastically — a typical response of the locals, who seem bewildered by foreigners, almost in awe of us, and often delighted to be in our company.

They are, however, forbidden from discussing politics with tourists. Their concerns about undercover police overhearing ensures that they obey. The locals were reluctant to talk with us about their country’s policies, and anxiously glanced around as they spoke to us.

In 1962, and again in 1988, a socialist military junta forced its way into power and has held the country in an iron grip, pillaging natural resources, crippling the economy and oppressing its people through human-rights abuses. Any citizen overheard talking state affairs with an outsider will find himself in a labor camp. As a foreigner, our only contact with any tourist-friendly authorities was an occasional road block or the requisite payment of a small government fee at some locales.

More than 35 years of suppression has attracted little attention from the United Nations, so human-rights groups and Aung San Suu Kyi, leader of Myanmar’s democratic movement and Nobel Prize–winning peace activist who is being detained by the dictatorship (on and off since 1989) urge people not to line the junta’s coffers through tourism. However, there’s a flip side. When I was planning my trip, I considered that the Burmese people needed a chance to eke out a living through tourism, one of the few industries to which locals had access — and most of them desperately wanted to open the eyes of the world to their situation.

Myanmar is a land of great beauty and intrigue, and its people are modest and respectful. On my trip in April 2006, there were relatively few tourists compared with the rest of Asia, and this lent itself to genuinely warm hospitality, adding further to its charm.

We eventually made it to Kalaw, a Burmese market town in the Shan Highlands that is popular with trekkers.

On the weekend, old wrinkled tribal women descended from the countryside to sell their produce, now that opium is no longer grown in the area. Dressed in colorful longi (traditional wraparound skirts) and headdresses, they sat cross-legged among their wares, smoking large, cigarlike cheroots. Hypnotic prayer was chanted over a loud speaker from the main temple day and night, punctuated by the occasional well-broadcast cough and splutter from the chanting elder, who probably smokes too much.

From our base at Kalaw we took a three-day hike to Inle Lake, the second-largest lake in Myanmar — 14 miles long by 7 miles wide (23 km by 11 km) — and one of the highest, at an altitude of 2,900 feet (884 m). Enormous water buffalo pulling wooden carts along dirt tracks occasionally passed us, with small naked children riding them bare-back. Workers cultivated fields, steering rustic wooden ploughs pulled by buffalo in the dry heat, and they all stopped and waved to us from a distance.

The scenery changed from rolling countryside to a surreal rust-red landscape of hills and canyons. Finally we came to a beautiful teak monastery in a forest where we stayed the night, awash with young novice monks timidly peering down at us from darkened windows. As part of Theravada — the oldest surviving school of Buddhism and the predominant religion in Myanmar — young men will typically take up the monastic robe and bowl at some point in their lives.

The people of Inle Lake (about 70,000) live in four cities bordering the enormous lake, surrounded by mountains. Stilted bamboo houses and shops perched above overgrown marshland and waterways. Women washed from jetties at the sides of their houses, while adorably happy children splashed alongside water buffalo, submerged but for their huge heads. In the distance, fishermen stood tall at the backs of their tiny fishing boats, while other boatsmen tended rows of floating crops. Flower gardens and rice paddies were also filled with workers. Golden towers and stone pagodas nestled in the surrounding hills, many lying in ruin and engulfed by trees.

After our stay at the lake, we traveled to Yangon — renamed from Rangoon in an attempt by the junta to distance itself from a colonial past — where the contrast was dizzying. Yellow colonial buildings lay dilapidated along tree-lined avenues that buzzed with rickshaws and comical pre-war vehicles that have been running since the British Empire left in 1948. Before Naypyidaw became the new capital in 2005, Yangon was the country’s principal city. It is still the largest metropolitan area today, with nearly 5 million inhabitants.

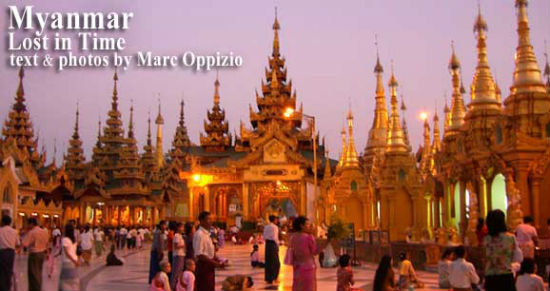

We were feeling a little templed-out, but Yangon’s mezmerising 322-foot-tall (98 m) gilded Shwedagon Pagoda (a religious monument) was a highlight; this enormous shimmering pagoda houses eight sacred hairs of Siddharta Gautama, the founder of Buddhism. Pilgrims teemed among the surrounding marble courtyards filled with lavish gold pavilions and shrines. The setting was incredibly serene, especially at dusk.

Dusk is when most of the city’s residents assemble on the streets for recreation: Groups of women stood around talking, while circles of men played footbag with a small bamboo football. Amid the vibrancy of people and traffic, street vendors were cooking piles of chapattis to mop up delicious lamb curries and bean soups, all adding to the unique flavor of this captivating country.

To Learn More:

CIA Factbook: Myanmar

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/bm.html