There is a saying in Moldova that goes something like this, “Eating makes me sleepy; when I wake up I am always hungry.” As a Peace Corps health volunteer in a small village in Moldova for two years, through late 2004, I think that sums up my experience: a mixture of cynicism and hope.

There is a saying in Moldova that goes something like this, “Eating makes me sleepy; when I wake up I am always hungry.” As a Peace Corps health volunteer in a small village in Moldova for two years, through late 2004, I think that sums up my experience: a mixture of cynicism and hope.

Moldova, a landlocked nation between Romania and Ukraine, is a country at the crossroads of history and culture. Heavily influenced by the Romans and the Ottomans, Moldova was a part of Romania until after World War II, when it was absorbed into Russia.

Upon declaring independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, the country fractured along cultural lines, with differing ethnicities and regions of the country claiming autonomy, promoting unification with Romania or refusing to recognize the new government. Russian forces have remained on the land east of the country’s Dneister River, claiming the area as its own republic, called Transnistria.

Culturally, ethnic Romanians are the majority population in Moldova, and Romanian is the national language. After decades of Soviet rule, however, many people still speak Russian. The country has gradually settled into economic depression — it’s the poorest nation in Europe — and corrupt politics.

Today, governed by a freely elected communist party, Moldova continues to try to find its way in a maze of cultural conflict and ineffective economic policies.

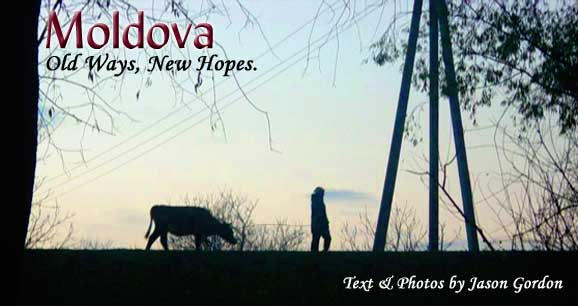

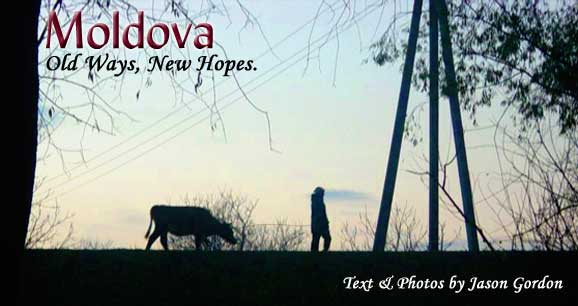

Moldova is a densely populated country, with large villages and towns surrounded by farmland. Despite its difficult past and continuing economic struggles, the country is blessed with a landscape of gently rolling hills, oak trees and numerous farms and vineyards.

The climate is temperate, with cold, snowy winters followed by warm springs and hot summers when fields of sunflowers bloom throughout the countryside.

Since the end of collectivization and the privatization of land, most families eke out an existence by laboring in the fields. Major crops include grapes, tomatoes, cucumbers, cabbage, corn, carrots, sunflowers, potatoes and beets. After the harvest, families preserve many of the fruits and vegetables for the winter, and the rest are sold for meager profits or kept to feed farm animals.

Moldova has been a center for grape growing and wineries since prehistoric times. The first institutions to become involved in winemaking were monasteries; today the country has scores of wineries producing high-quality wines. The climate is ideal for grape growing, and nearly every family has its own grape vines and produces homemade wine each fall.

Be sure to visit one of Moldova’s wineries, such as Cricova or Milestii Mici, for a tour and wine tasting. On a tour of Milestii Mici, you will be treated to a walk through an immense underground limestone labyrinth — with underground streets you can actually drive through, named after various grapes — housing an amazing quantity of wine.

You are then given time to sample wines. If you wish to purchase any of the wines, the price is quite unbelievable by western standards.

Moldova holds some interesting sites for the traveler, including many beautiful Orthodox monasteries. Orhei Vechi, an ancient monastery built in a cave overlooking a beautiful valley, is the most famous.

The country’s culture is based on hospitality. This can take some getting used to for non-locals. For instance, accepting food and drink upon entering a house is the guest’s obligation, not choice — unless you want to insult your host.

Once when coming home from work, I was invited into a villager’s house for a drink. Upon politely refusing, I was taken by the arm and steered into the house to drink vinegary homemade wine and discuss historical ironies. Talking about work always comes after polite discussion, and polite discussion often turns into a time-consuming meal.

Overall, life is slow and hard. Many people have to find work abroad to support their families, and the government is notoriously inept at fixing even the most basic problems.

As in much of Eastern Europe, Moldova’s population is still recovering from the collapse of communism, with people looking backward longingly for things like free education, free health care and universal job security.

This is what makes working in Eastern Europe difficult. How do you promote healthy habits and viewpoints to a person who has literally seen his or her world collapse? How do you talk to someone conditioned to the idea of group identity, traditional gender roles and rote memorization about the virtues of independence and critical thinking?

How do you convince a person who has been taken care of by the state for most of their life that they need to take care of themselves? Change comes slowly. Mostly the young are desperate to leave their communities and their country. An estimated quarter of the population works abroad.

As a middle school health teacher in a village on the eastern border, I learned that the most effective tool for combating despair and passivity is by setting a good example. During a classroom discussion on healthy lifestyles in class, a student argued that smoking and drinking was what every real man did.

By saying, “I don’t smoke, I don’t drink, I am a man,” I pointed out the flaw in his argument. My well-behaved classroom served as a model for other teachers to see that corporeal punishment wasn’t necessary.

In the fishbowl that is a Moldovan village, the only outside information comes from the television, which features American movies and Russian news and entertainment programs. By simply being myself and being open, my students and the people around me found that Americans weren’t all rich and petty, consumed with fast cars and fancy clothes.

Seeing my students and counterparts begin to think differently and initiate change in their lives was incredibly inspiring, but tempered by the acknowledgment of the overwhelming forces of tradition and history set against them.

In contrast, Chisinau, the capital city, situated on the banks of the Bac River and surrounded by parks and lakes, has a vibrancy about it largely due to the influx of foreign diplomats and businessmen who regularly stride down its lovely green avenues.

The stately old buildings look like something you would find in parts of Vienna or Paris, albeit they are dirty and rundown looking. Among the city’s attractions are the Museum of Nature and Ethnography; the National History Museum, with its life-size diorama of the 1945 Soviet invasion of the city; and Exhibition Hall, which features contemporary art.

The real spirit comes from the richness and diversity of the city, where huge outdoor markets compete with modern department stores, and elegantly clad youth intermingle with poor commuting villagers.

Full of fancy boutiques and great restaurants (try Green Hill Nistru, New York or La Taifas), the city seems far from the daily life of most Moldovans. The grandmother selling wine and watermelons by the side of the street is the only reminder of the life of the majority of the population.

Tourism isn’t developed much outside of the capital and public transport can be confusing, but with a guide, you shouldn’t have a problem. My advice to those interested in visiting Moldova is to remember that as a country in transition, it is important to keep an open mind.

Though the capital city of Chisinau is convenient and enjoyable, with hotels, restaurants, bars and clubs, try to make it out to the countryside to see how the majority of the population lives.

If You Go

Department of Tourism Development: www.turism.md/eng

- What is Altitude Sickness and How Can You Avoid it? - June 18, 2025

- Cinnamon Bay Campgrounds, U.S. Virgin Islands - January 10, 2021

- Colorful Colonia del Sacramento, Uruguay - January 9, 2021