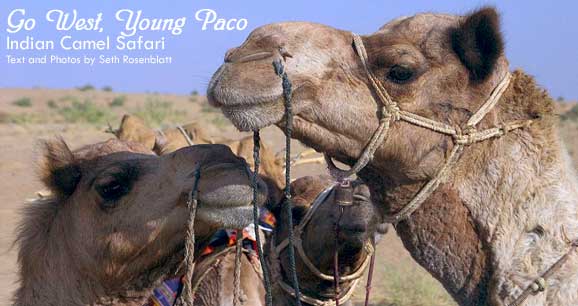

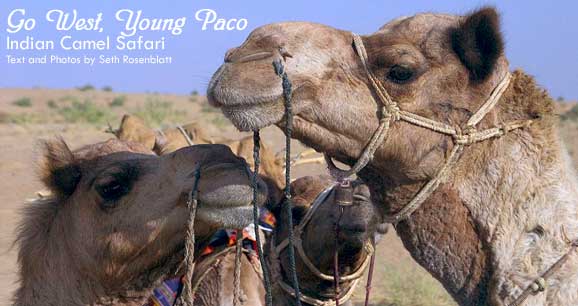

When talking to several camel safari operators in Jaisalmer, India, they all assured me that the trek was worth it, despite the pungent aroma of the dromedaries, as if the camel stink was something foreigners could handle only with advance notice.After spending two days perched on one, though, I can say that the stink just wasn’t a big factor on my trip. They didn’t smell like roses, but maybe I just got used to the stench of mine; I called him Paco.

When talking to several camel safari operators in Jaisalmer, India, they all assured me that the trek was worth it, despite the pungent aroma of the dromedaries, as if the camel stink was something foreigners could handle only with advance notice.After spending two days perched on one, though, I can say that the stink just wasn’t a big factor on my trip. They didn’t smell like roses, but maybe I just got used to the stench of mine; I called him Paco.

Paco was a bit young for safaris, and the guides said that it would be dangerous to use him for treks without a human lead walking alongside him. He, and all the camels used for schlepping are always “he,” because the she-camels are larger and prone to driving their male counterparts into hormonal rages that end in what can only be described as the dromedary with two humps.

I was the only tourist on my trek to suffer the trauma of having a horny adolescent camel. The other four tourists on the trek, including my traveling companion—my Financial and Menu Adviser—were able to guide their own camels with their own reins. There were five of us: Stu, the Canadian; Tim and his girlfriend Mel, a British couple; and the FMA and I.

Stu was wacky.

He had a digital video camera with a separate lens component that looked like military or spy hardware strapped to a headband. The recording part of the camera was positioned on his belt. With his longish red hair, he looked a bit like Richard Simmons gone Borg. While the locals we would encounter clearly enjoyed discussing him, none of this made him memorable.

What really made Stu unforgettable was that he rarely walked upright. He bobbed and weaved, his thin, pale white arms with their dusting of red hair spread out for balance. He crouched low, then rose up high, like a cross between a boxing instructor and a DIY infomercial on how to shoot extreme sports.

Stu was friendly, too, a nice guy with a genuine interest in what went on around him, but whack-a-mole wacky. He’ll probably win an Oscar someday.

Tim and Mel, on the other hand, were the antithesis of Stu. Clean-cut Londoners, they provided a perfect balance to Stu’s optimistic bob-and-weave. Pleasant to talk to, willing to share the more embarrassing moments of their trip as eagerly as the exciting, frustrating or horrific ones, it was nice to meet others who enjoyed India, but didn’t think that it was some kind of mysterious magical wonderland.

With Paco and I at the tail of the line, we trudged westward with our guides, past the brown desert scrub and toward the sand dunes north of the town of Sam. We ate during the hottest part of the day under some scrubby trees on the edges of the dunes. The guides helped us dismount, with much gronking and chortling from the camels, and then they cooked us an authentic desert meal: rice, chapatis, dhal and some kind of curried desert vegetable.

The guides used very little water when cleaning the dishes. They used sand for soap, which resolved the issue of waste by absorbing anything left over. When we left, the dung beetles that infested the sands moved on the remains like large black maggots.

From the larger mammals to the occasional bird and the ubiquitous insects, the desert boiled with a curious stew of creatures. People, too, populated the scorched, scrubby plains and shifting dunes. As the camels and our guides slowly plugged along into the four o’clock sun, we came upon a lone tree with red strings tied all over its branches: a Hindu cemetery, explained the guides.

Soon after, I saw a village spread out on the horizon. Much closer, a group of cisterns and wells was being used by the villagers. We dismounted to get water for the camels, so I went over to the locals. Ignoring me as they chatted among themselves, they pulled water up from 70 meters below the surface of the sand. When the rope reached the top, I was surprised to see it wasn’t attached to one of those cheap plastic buckets found all over India.

Instead, the rope was tied to the four corners of a piece of brown leather. Pulled up like a baby’s nappy, it looked like it held a frightfully small quantity of water for the effort required to haul it up.

Over and over again, it was dropped then hoisted, and its contents dumped into containers, into hands, onto heads. For a place that measured its rain not in centimeters but in years, as in, “We haven’t had any measurable rain in two years,” they seemed absurdly wasteful of such a precious commodity.

After about two hours of more camel riding, we closed in again on the dunes. The sun fell lower in the sky, and our shadows, elongated on the sand, became a photo-op for Tim and Mel. Restricted to the top of his camel, Stu’s bob-and-weave videography was limited to the cadence of his carrier.

Before we knew it, we’d reached the center of the dunes. Only on the edge of the horizon did the sine wave of sandy hills flatten to infinity. After dismounting, the FMA and I walked away from where the guides were unsaddling our rides, for the night.

Confronted by such enormous, overwhelming repetition that somehow wasn’t repetitive, we parked our sore butts and legs on the sand and watched the sun slip below the horizon. The pollution from Pakistan floats eastward, so the sun turned an angry red and then dropped out of sight far above the horizon. While our view of the sunset was utterly undramatic, it was the same one that the large group of day-tripping tourists on a nearby dune saw.

Dinner came and went, and tasted the same as lunch, even if the food was different. Indian beer wasn’t much to speak of, either, with a marginal alcohol content to match the marginal taste. Before the beer was gone we were interrupted by one of the guides. The moon was rising.

We clambered up the dune to be greeted by a big fiery ball of white. The valleys and mountains on the moon’s surface were visible to the naked eye. The dunes were almost as bright in the moonlight as they were four hours earlier, in daylight. We all stood in awe. Tim even proposed to Mel, choosing what she later called “the perfect night” to ask her to marry him.

The second day brought me Paco 2.0, an older and more mature camel than the first, which I was able to lead on my very own. It was like graduating kindergarten. And just like back in kindergarten, it didn’t take me long to find myself getting chastised. One guide told me not to kick in my heels to get P2 to speed up, since that upsets their stomachs.

Camel welfare, however, did not interfere with the same guide repeatedly beating another camel on the neck with his fist, when the beast misbehaved. I thought about pointing out this irony to the guide, but decorum and a severe language barrier got the better of me.

The village of Sam, a collection of a dozen huts and three dozen piles of trash on the ground, was unremarkable. There were no local crafts that were pointed out to us, no obvious reason why the village was even there.

At the end of the trek, we visited a well where many women were, collecting water in steel jugs that they balanced on their heads. Our guides wouldn’t let us approach them or even ask questions from across the well, but at four in the afternoon it was damn hot to be carrying steel jugs anywhere.

All I could take away from the camel safari, besides another interesting, yet not fantastic Indian adventure, was a reminder of a Zen moral translated in 1990s parlance: It’s the experience, stupid.