![LEADchiliRainbow[1]](https://www.goworldtravel.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/LEADchiliRainbow1.jpeg) White-dusted mountain peaks frame the trail of frothy waves left behind by our fast-moving catamaran. Rain is gently falling upon us when, all of a sudden, I see streaks of sunlight struggling to break through the cloud cover.

White-dusted mountain peaks frame the trail of frothy waves left behind by our fast-moving catamaran. Rain is gently falling upon us when, all of a sudden, I see streaks of sunlight struggling to break through the cloud cover.

“Look, a double rainbow!” a fellow traveler blurts out. What follows next is a cacophony of mechanized clicks and zooms as we grab our cameras, not wasting a precious moment. The scenery, it seems, changes constantly as rain clouds quickly give way to sunbeams burning through a misty and craggy panorama.Within minutes, we’re all comparing our digital photos. It’s a good thing we snapped those pictures so quickly. The rainbow is now gone, fading away as quickly as it appeared.

I soon learn, however, that seeing a full-banded rainbow in Chile’s Northern Patagonia – even a double rainbow against this dramatic backdrop of mountainous Pacific coastal islands – is not unusual along the intertwine of fjords here.

Several times a day, wind-driven rain lasting only minutes gives way to the deep yellow sunbeams of the Chilean spring, instantaneously illuminating the horizon with a rainbow’s colorful bands.

“It’s a secret in this hidden place in the world,” tour guide Rodrigo Mansilla tells us. “You have to brave a long trip to get here and then deal with the weather to discover this secret.”

This is only the beginning of my adventure through Chile’s Aisén region, supposedly named, as the locals will tell you, after remarks by naturalist Charles Darwin and others on how this area is where the “ice ends.” Aisén is sparsely populated with only about 90,000 people living along a shoreline of rugged, mountainous islands.

As we continue our journey, the sun casts long shadows, illuminating lush rainforests and misty mountaintops with pale green and yellow hues.

With hardly another boat in sight, our catamaran, the Patagonia Express, is whisking us within this very remote corner of the earth to Puyuhuapi Lodge and Spa, where we will spend our evenings and nights, with its healing baths of glacier-fed thermal springs.

After flying in from Santiago, our traveling began earlier in the day from the Balmaceda airport where we boarded a tour bus. We traveled along grassy countryside and river valleys on our way to the small port town of Puerto Chacabuco, where the Patagonia Express awaited our arrival.

On the way, we visited Coyhaique (population 50,000), the largest town in the Aisén region with its five-sided central square, where vendors sell handicrafts based on their indigenous heritage.

“It’s the only square in Chile that’s not square,” I recall Rodrigo saying with a laugh.

By nightfall, we finally arrive at the Puyuhuapi Lodge and Spa, where a sign reads “Bienvenidos Pioneros,” or welcome pioneers. It’s a greeting that’s not far off base considering the lodge’s scenic location along quiet Dorita Bay surrounded by mountains and glacier-fed streams.

Key to this location are the nearby natural thermal springs spewing heated water that constantly flows through the spa’s hot baths and pools. It’s the main reason lodge founder Eberhard Kossmann situated his bit of paradise here, and why he built the Patagonia Express to conveniently bring visitors to this small corner of the world.

The next morning, hiking guides Mauricio Ulloa and Daniel Muñoz lead us through Queulat National Park, where we will glide across a glacial lake to the edge of Ventisquero Colgante, the Hanging Glacier.

“Queulat means ‘far lands,’” Mauricio says while walking through this 340,000-acre (137,593 hectare) rainforest filled with moss-slicked rocks and budding ferns. “Everything is very green. Feel the tranquility of this very wild place.”

When we reach the glacial lake, we clearly see the Hanging Glacier atop a mountain in the distance. It doesn’t take long before we see chunks of its 24,000-year-old ice tumble hundreds of feet below.

Donning life jackets, we board a small boat to get a closer look and are soon chilled by downdrafts of frigid air.

“The wind of the glacier is coming. Can you feel it?” Daniel exclaims.

I stretch my neck upward to see torrents of water streaming down into lake-like fingers gripping the mountainside.

Back at the lodge, I embark on an afternoon kayaking adventure. Clouds roll in once again and we’re soon paddling through a brisk, cold rain shower. Sure enough, a rainbow emerges when the first rays of hazy sunshine break through.

The next instant brings a moment of serendipity. “Stop!” I yell to a fellow kayaker. He does so and sits motionless. From where I sit, he is centered beneath the elusive rainbow, framed in my camera’s viewfinder as if he could paddle directly under it.

Early the next morning, it appears the mighty Pacific Ocean is still asleep as the fjords are particularly smooth and glassy. It’s 7 a.m. and we’re heading out for the highlight of our Northern Patagonia adventure – a seven-hour trip aboard the Patagonia Express to the San Rafael Glacier.

Dramatic views of forested islands with white-capped mountains again surround us as Captain Cristian Dagnino maneuvers the catamaran through the maze of fjords.

“It’s like an amazing puzzle to me,” he says. “There are many ways to navigate and many ways to arrive at the same place.”

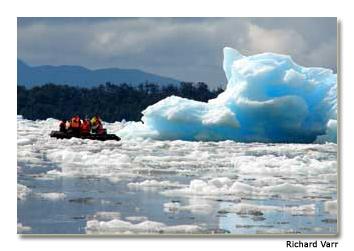

When we finally approach the glacier, the skies are blue and surprisingly clear. Sunlight reflects off floating icebergs, illuminating iridescent shades of cool blue deep within the ice.

The color depends on the ice’s age and the amount of light. “Older ice has less oxygen inside and that means the ice will appear much bluer,” points out Rodrigo. “This ice is old – 20,000 to 24,000 years old.”

The San Rafael Glacier is 24 kilometers (15 miles) long, standing 70 meters (234 feet) above sea level at its highest point. It’s retreating at a rate of about 100 meters (330 feet) a year. Despite clear skies, the cold mass has created an icy fog that shrouds the glacier.

“The sensation is like a big freezer in front of you,” jokes Daniel.

To take a closer look, we board a motorized raft. We’re soon cheering and clapping as we zip around one of the huge icebergs, while mindful of the possible dangers. We eye overhanging pieces that could at any second plummet into the sea and cause a thunderous splash that could capsize our raft.

Back on the Patagonia Express, crewmembers chip away at a giant ice chunk and bring pieces to the bar. We’re soon engaging in the Patagonian tradition of sipping whisky and the local favorite drink, pisco sour, a regional brandy, chilled with the 24,000-year-old ice.

As we begin our journey back to the mainland, we watch what seems like multiple sunsets as the sun dips below one mountain peak, and then, because of the moving boat, reappears, and then dips below another mountaintop and then another.

With the deep darkness of nightfall, Rodrigo points out the Southern Cross amid clusters of stars.

At this moment, I recall what Captain Cristian told me earlier in the day. “I like this job. For me, it’s a way to explore Chilean Patagonia, this unspoiled place on the earth – untouched in so many ways.”

If You Go

www.patagonia-connection.com

A former television news reporter, freelance travel writer Richard Varr is a member of the Society of American Travel Writers (SATW). His work has appeared in newspapers including The Christian Science Monitor, The Sydney Morning Herald and The New Orleans Times-Picayune; and in such magazines as Porthole Cruise Magazine, Highways, The Rotarian, New Jersey Monthly and German Life.

- How to Get Around in Sydney: A Local’s Guide to Traveling Around Sydney - April 24, 2024

- The Low-Key Magic of Ghent, Belgium - April 22, 2024

- Discover the Hidden Charm of Extremadura in Spain - April 20, 2024