No one would claim that the ’20s and ’30s were perfect years, but they had a sense of style and sophistication that has never been forgotten. That style lives on at Art Deco Napier.

Napier, a town of 56,000 in the heart of Hawke’s Bay wine country on New Zealand’s east coast, throws itself with enthusiasm into the past: Every year on the third week of February, locals and visitors dress to the nines. Hundreds of spit-and-polish vintage autos cruise along Marine Drive, big band music wafts through the air, and laughter is everywhere.

Some visitors return annually. Anne and Geoff Beetham of Auckland have been here eight times: “Every year we say we won’t come again, and every year we come again,” she says. George and Iris Phillips of Orewa (north of Auckland on the Hibiscus coast) have been twice “and we’re booked for next year,” he says. Phillips, 75, loves to sing and is often invited to join the men’s choir that strolls through the heart of the downtown area. “It’s fun,” he says, with a big smile.

Peter Mooney, Art Deco Festival coordinator, tells the story of an English woman who made her first visit to the Art Deco Festival in 2003. “She wore a long gown with a train. She said it was the gown she had worn when she was presented at Buckingham Palace,” he says. This year she returned to the festival, with a dozen friends in tow to this North Island city.

Napier (a four-hour drive north of New Zealand’s capital, Wellington) is a popular retirement and tourism center, set among rolling hills where sheep farms, orchards and vineyards flourish, and agriculture — mostly vineyards — is the main industry.

The city was destroyed by a massive earthquake (7.8 on the Richter scale) on February 3, 1931. Only a few buildings in the downtown area survived and 162 people died. Napier was rebuilt in just two years.

At that time Art Deco was fashionable. It was safe, as all new buildings had to be built of concrete — a material then thought to be resistant to earthquakes and fire. And it was cheap to build with concrete. The typical relief stucco ornaments were an economical way to beautify buildings during the Great Depression. Today, Napier is said to have the largest collection of Art Deco buildings outside Miami. It was from tragedy that today’s treasure was created.

Art Deco was a movement in decorative arts that also influenced architecture. Its name was coined during the World’s Fair held in Paris in 1925, which was formally titled “Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes.”

Art Deco, which is considered to be eclectic, was a major style in Europe from the early 1920s. It is characterized by use of organic materials such as sharkskin and zebra skin, zigzag and stepped forms, bold and sweeping curves, chevron patterns and sunburst motifs. One example of the popular sunburst motif is the spire of the Chrysler building in New York City.

It was an opulent style, attributed as a reaction to the forced austerity during the years of World War I. By the late 1930s — the decade perhaps most strongly associated with it today — it was in its Streamline or Streamline Moderne phase. This followed manufacturing and streamlining techniques arising from science and mass production. After World War II, the International Style, devoid of all decoration, dominated. Not until the late 1960s did people begin to rediscover Art Deco as a symbol for vigor and optimism of the Roaring Twenties.

Carol Hall, an ex-patriot American who has lived in New Zealand for 13 years, bought 10 outfits for the festivities. On Friday night, she was clad in a beige dress and fur stole and a snappy little brown hat. Her “gentleman friend,” Bruce Cato, dressed in a tux and bowler hat. For Saturday, Carol chose an outfit all in white for a ride through town during Automobilia, an Art Deco vintage car rally with more than 150 participating vehicles. And on Sunday, she donned a fur-trimmed off-white dress for the Gatsby picnic in the park along Marine Parade.

“You’ve picked the best weekend to be here,” Carol tells me. “Everybody has fun. Everybody looks fantastic.” It’s a good thing to return to the past once in a while, she adds. “We’ve lost a lot of style.”

But there’s no loss of style this weekend.

Even two-year-old Roman Walewski dons a tiny tux and bowler hat. He is the spitting image of his father, Cornel, who wears the same duds, while his mother, Amy, is a brilliant flapper in blue.

Hundreds of others join in the fun, flappers and swell fellows in sporty jackets and boaters, to say nothing of those wearing black suits, white ties and carrying violin cases. Max Patmoy chooses a different kind of costume; each year he arrives dressed as Charlie Chaplin’s “little tramp.” He’s become a fixture at the festival, particularly at the “Depression Dinner,” held on Saturday night.

About 250 people start their evening at a “soup kitchen” at Marine Parade, then stroll, tin mugs in hand, a few blocks to Clive Square where long, paper-covered tables have been set up at a marquee. En route, some stop at an outdoor pub to fill their mugs with beer. Others use them as begging bowls.

“I’ve got NZ$ 1.65 here,” one woman laughs. “Soon I’ll have enough for the illegal gin.”

Dinner is lamb stew served on tin plates and accompanied by slices of white bread. It’s a raucous crowd; there’s much banging of tin mugs on the tables in response to the music and jokes from the quartet that entertains us with songs of the ’30s. But it’s not all Depression-style: wine and beer are available. Unlikely that would have happened at the soup kitchens of the 1930s.

The Art Deco Weekend got its start in the early ’80s, coordinator Peter Mooney explains, when a group of visitors from the International Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) said: “Do you realize what you’ve got here?” After that, “a few enthusiasts created the first Art Deco walk. They expected a couple of hundred walkers. About 1,200 people turned up,” he says.

In 1987, the Art Deco Trust was established. “They made a very sensible decision,” says Mooney, “because the Trust really has no legal powers to stop people destroying the buildings. So, it was decided, if we can make these buildings a tourist attraction, then the locals won’t let the owners tear them down because the tourism brings money into the town.” In 1989, Art Deco Weekends were started and the fun began.

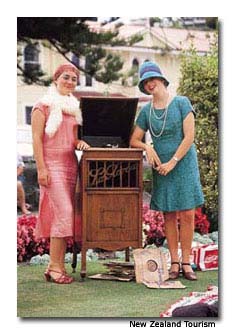

On Sunday, gazebos are set up on the seaward side of Marine Parade Park on Sunday for the Gatsby picnic. Families and friends gather to dine at tables set with white linen, fine china and silver tea sets. The menu includes tiny party sandwiches, elegant cakes, strawberries and cream, and tea. There is also a good deal of bubbly available, chilled in 1930s-style ice buckets. Some have even brought along wind-up phonographs on which they play songs from the “good ole’ days.”

But Anne and Geoff Beetham choose to dress down. They are clad as a ’30s couple hit hard by the Depression: She’s wearing a burlap skirt, cotton blouse and a kerchief; he’s wearing cotton pants and shirt and a vest. They have spread a blanket on the grass and are dining on onions, bread and water. After all, it was not all music, dance and bubbly in those long-ago years.

If You Go

Art Deco Trust Napier

Tourism New Zealand