Brexit be-damned, the Hastings Europa Hotel in Northern Ireland continues to throw open its borderless doors to the many tourists now visiting Belfast – a capital city of history and intrigue to the six counties that make up most of Ireland’s Ulster province.

If you’re baffled by the geographical references, that’s good, according to tourism industry professionals who would rather visitors not focus on the political distinction between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, which many tourists are surprised to learn are two different countries flying three different flags with two different currencies…on one island.

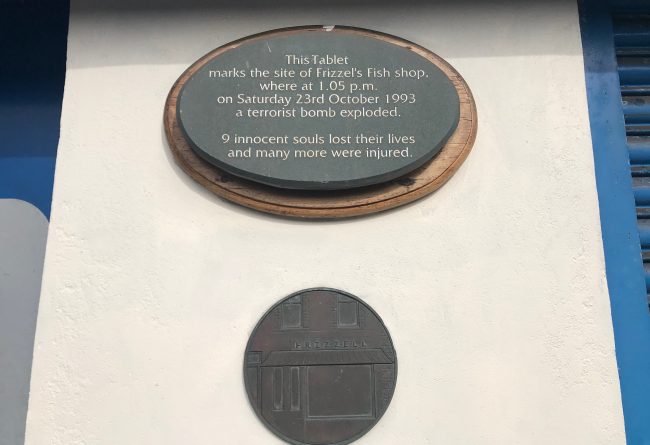

A hard border separating Ireland from Northern Ireland was eliminated in 1993 and all visible evidence of security checkpoints and customs stops were gone by 2006. But in Belfast, a different type of border remains visible: the giant walls often painted with striking political messages separating the city’s Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods. Those dramatic walls draw tourists via Billy Scott Black Cab Tours.

“The walls were put up in the late 1960’s and 1970’s to separate communities which were fighting each other by burning each other’s homes to the ground. The government likes to call them ‘peace walls,”’ said Des Hand, a former activist now guiding tours from behind the wheel. “The Good Friday peace agreement called for the bringing down of the walls and fences by 2020 and we need to make sure that is implemented. But to bring down the walls, you’ve got to bring down the walls in people’s brains and hearts.”

Peace Walls of Belfast

The walls and their elaborately painted, dramatic political messages are striking and the memorials both sad and frightening in their intensity.

“We show the political murals and try to explain what they are representative of. Some say the British Army have occupied Ireland. At one time, there were 30,000 troops here patrolling the streets. They’re gone now due to the Good Friday Agreement. The idea of these tours is to show people the history of the Troubles without prejudice. We explain the position of both sides,” said Hand.

After parking the cab next to a particular memorial Hand explained that he would not be leaving the car.

“What you will see in there are some very graphic images told from one political perspective,” said Hand.

He was right. The photos and captions detailed atrocities and bombings and compared their perpetrators to terrorist organizations such as Isis and Al Qaeda.

“The reality of life in Belfast is that the vast majority of people have moved on from the conflict. But we don’t have integration – we still have large parts of society and schools segregated. It’s unfortunate because of the religious and political aspects of the situation,” Hand admitted.

The Europa Hotel Beats in the Heart of Belfast

The landmark, four-star Hastings Europa Hotel holds an important place in both Belfast’s past and present.

“We are the original hotel in the heart of the city,” said the Europa’s James McGinn, who has been voted the best hotel general manager in Northern Ireland and has directed the property since 2003. “We were built in 1971 and through the Troubles we suffered 33 bombs in that period – the last being in 1994. We are now the symbol of hope and prosperity and everything that’s great about living in Ireland.”

U.S. President Bill Clinton was instrumental in the Irish peace process, during which his presidential entourage booked 110 rooms at the Europa in 1995. Clinton’s room 1011 is now named the “Bill Clinton Suite” and his stay is celebrated by a circular plaque behind the reception desk.

Clinton is one of many presidents, prime ministers and celebrities who have enjoyed the prospect of Bushmills Whiskey in their porridge during the Europa’s Irish breakfast buffet or live jazz music performed in the lobby bar with Six-Nation’s rugby showing simultaneously on the television. The Glasgow Rangers legends hold a reunion each year at the Europa and in 2011 MTV Europe staged its Music Video Awards there featuring pop-stars Justin Bieber, Lady Gaga and others.

Bustling Belfast is Buzzing

Like the Europa, Belfast’s city center is snazzy and stylish with plenty of traditional architecture, too. City Hall at night is an up-lit, bejeweled building and there are many nightclubs, restaurants, shops, and the Titanic museum, with young, vibrant people buzzing between places like Kelly’s Cellars, a cave-like pub built in 1720.

The fanciful Opera House is next to the Europa and near classically ornate Ulster Hall, where I watched the famed Irish stand-up comedian Tommy Tiernan, who also stars in the smash hit television series “Derry Girls” seen around the world on Netflix, perform. The first 10 minutes of his act, comprised of sensitive political jokes and rants about the Troubles, and Catholics and Unionists provoked some of the audience members to walk out in protest and phone the police.

So, yeah, the sectarian tensions are still right there, just below the surface.

While watching a rugby game in a Belfast pub, my colleague toasted one of the patron’s we’d just met with the commonly known phrase “Slainte,” meaning “to you health.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” the suddenly straight-faced reveler replied.

Later, at Le Parisien, the chic French restaurant across from City Hall, my colleague again got a smack back when he wished a waitress “Happy Saint Patrick’s Day.”

“Not for everyone,” she barked back.

We both shrugged.

Exploring Belfast

Deciding it was time to get out of the city center, we went back to the New Lodge neighborhood Hand had driven us through during the Black Cab Tour and ventured into McGrath’s Pub. It was the kind of authentic, simple, clean bar the Irish would describe as a “local,” so we were quiet and respectful, but were quickly engaged in conversation by the regulars who immediately identified us as American tourists.

When the moment seemed soft, I carefully dipped my toe toward the subject of politics…but found out that was more like jumping into the deep end of the pool. With the slightest show of interest they were instantly ready to talk about the loyalist gunman on New Year’s Eve in 1997 who came in with a rifle – killing one and injuring 12.

“The bar used to be along the front all next to the door,” one of the patrons explained as he sipped a pint I’d bought him (after he’d bought me one). “After that the place was redesigned so that the bar is here in the back so the bartender can see who comes in.”

Another friendly fellow, who’d moved up from Dublin, leaned in and whispered, “You see that white haired fellow down at the end of the bar? He was big in the IRA.”

The Irish Republican Army was originally the enforcement wing of the now political party named Sinn Fein, which ultimately desires a unified Ireland via the end of British rule in the North.

The Ulster Unionist party had its own paramilitaries, and the charming bartender Patricia hooked her smart phone up to the television behind the bar to show us YouTube video of a recent, planned loyalist march that resulted in the police using water cannons and rubber bullets to control crowd of Catholics who’d come to peacefully protest.

One of the patrons guided my fingers onto the area above his right knee so I could feel, through his jeans, the permanent scars left by the rubber bullets. By law, he explained, the police aim so the bullets ricochet off the ground rather than aiming directly at a human target.

Old St Mary’s Church, an Oasis of Peace

That evening, during Mass at Old St. Mary’s Church back in the city center next to Kelly’s Cellars and Manny’s Fish and Chips shop, I closed my eyes and allowed my mind to wander over how beautiful the Northern Ireland’s Antrim coast is and how lovely its’ everyday people truly are.

Near the end of Mass three female musicians, including teacher Barbara Fitzpatrick, played a gentle melody I recognized as “The Green Glens of Antrim.” The lyrics are a love song to Northern Ireland’s County Antrim. “’Till I know every stone I will recall every tree where the green glens of Antrim are heaven to me…”

The congregation in the peaceful old church was silent when the musicians concluded the song. With tears in my eyes, I badly wanted to clap for them, but wanted to be respectfully appropriate in the church.

Suddenly the old priest Father John Nevin, standing at the lectern microphone, broke the silence when, in the thickest but softest brogue imaginable, uttered, “Wasn’t that beautiful?”

The heartfelt statement subtly and elegantly gave the gathered the permission to shower the musicians with appreciative applause.

Michael Patrick Shiels is a radio host and travel blogger. Follow his adventures at GoWorldTravel.com/TravelTattler. You can contact him via [email protected].

- e.baldi is Beverly Hills Best Italian Dining Delicacy - April 23, 2024

- Ashford Castle Hotel, U2’s Bono and Why Visting Ireland is So Entertaining - March 28, 2024

- Solo Travel to Oceania Cruise Ports St. Barth’s and Barbados Became Authentic Cultural Encounters - February 27, 2024