Every year, 31,000 climbers fly from around the globe to northeastern Tanzania to climb Mount Kilimanjaro. It’s easy to see why.

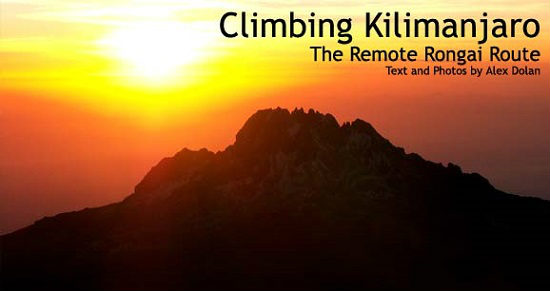

From miles away, the solitary volcano rises from the plains and dominates the landscape, cutting through the clouds and peaking in a flattop.

Climbing Kilimanjaro

Most climbers trek up the Marangu Route, which has earned the name “the Coca-Cola Route” after the hordes of Americans who use the route.

The 12 members of my hiking party are looking for something more remote, and we find it on the east side of the mountain.

Rongai Route

Our path is the Rongai Route, close to the Kenyan border. This relatively undisturbed route promises majestic views and a buffet sampling of the African wild, as it cuts through verdant jungle, alpine desert and glaciers.

We start our 10-day trip from the Kibo Hotel at the base of the mountain, in the town of Marangu. Jimmy Carter stayed here in 1988 when he climbed Kilimanjaro.

But the cozy compound, draped with autographed jerseys of those who’ve summited, feels anything but presidential.

In the morning we pack the Land Rovers and head out on rocky, red clay roads. For three hours, the extreme vibration of the truck makes me feel like I’m in a hardware store paint shaker.

Forehead pressed to the window, I take in the banana fields, and wave to barefoot children who line the road dressed in bright colors, on their way back from church.

It’s a relic from the 1930s with aged tin roofs and, between the springy twin beds and the dim corridors, it has a distinct dormitory feel. Here at the foot of the mountain, the thick palm trees still tower over us.

As we get closer, there’s something out of place about the mountain. It sticks out from the landscape like the monolith from director Stanley Kubrick’s movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, and it’s hard for any of us to take our eyes off it.

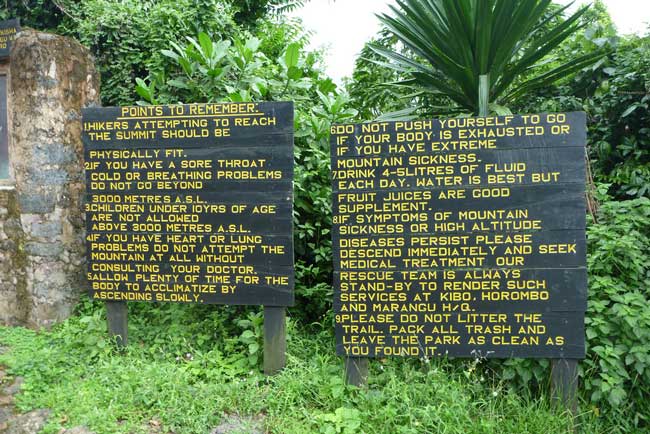

For an amateur hiker like me, Kilimanjaro offers a unique opportunity. At 19,340 feet (5,895 m), it’s the highest mountain in Africa, and the highest peak in the world that’s not part of a mountain range.

Situated just south of the equator with a relatively gentle incline, it’s also one of the few mountains in the world this high that you can ascend without technical climbing skills.

During our previous briefing by the head guide at the hotel, we’ve been told we can all make it, but I’m still nervous, and unsure about how I’m going to adapt to the altitude.

That’s the biggest challenge of the mountain, and for the past six months I’ve been training to prepare myself. One rule of thumb is that you should be able to run for a half-hour straight before you attempt the climb.

My training consisted of runs and trips to the gym, but you can do anything that will build up your cardiovascular endurance.

It’s a slow pace, but if you go on an organized tour, you’ll likely be hiking for four to eight hours a day (and as many as 17 hours on the summit day).

There’s also a lot of required equipment. Your travel agent should provide a list of recommended gear. Follow it to the letter. I did, and was thankful later.

To see how you’ll adapt to the altitude, you can try to climb a high mountain, but if you don’t have one nearby, just try to build up your endurance.

A word of caution: Those who are hypoglycemic or have low blood pressure should consult a doctor before committing to this.

The altitude will affect you more than others. That being said, my climbing team ranges from 25 to 64 years old, and includes a wide span of fitness levels.

On the plus side, if you go on an organized tour, you’ll have help. The porters outnumber our hiking team by about three to one.

These guys are mountain goats, putting us all to shame by hauling up tents and cooking equipment twice as fast as we can climb, so by the time we arrive, all of our sleeping tents and the larger mess tent are already dotted about the campsite.

The guides and porters are all extremely friendly, and they provide some essential encouragement along the way.

After unpacking the Land Rovers, we start out at an unmarked trail head with a view of Kenyan farmland below us. It’s sunny and hot, and we strip down to T-shirts and shorts before walking slowly through a half-mile (800 m) of maize and sunflower crops.

The stalks are as tall as us, and I occasionally spot a bulge of ripening maize in its husk.

The incline is slight, and although we’re only at 6,000 feet (1,829 m), the pace is polepole — Swahili for “slowly” — a word I come to love throughout the six days of the trek.

I’ve been on safari for the past nine days, and after more than a week of wildlife watching from a vehicle, my unused legs have the consistency of Kobe beef. I relish the slow pace.

The terrain changes quickly from cornfields to rain forest. A thick forest canopy blots out the sun, and we find ourselves on a narrow, root-heavy path lined by ferns.

Beneath towering, moss-coated avocado trees, the air is rich with damp, earthy odors.

We’re even lucky enough to see monkeys hiding in the foliage. Soon, we’re out of the forest and back in the sun, winding through shrubs on the way to camp. I focus on my breathing as a warm up for what’s to come.

The first night it snows at the top, giving the summit a sugary dusting of powder, but the equatorial sun melts it within an hour of sunrise.

The incline gets a bit steeper and the air a bit colder. Shrubs and heather cover this part of the mountain like a coat of fur.

At first, the vegetation reaches to our shoulders, but the higher we climb the shorter the shrubs, until they’re only ankle high.

At this point, we can look out over the Kenyan plains for hundreds of miles.

In the mornings and evenings, we convene in the mess tent for porridge and soups that can help us hydrate for the long days. I was expecting swarms of mosquitoes, but they stay below 6,000 feet (1,829 m).

The nights in our tents are progressively colder, and even in my thick sleeping bag, rated to minus 10 degrees Fahrenheit (-23° C), I wear thermal underwear.

Mawenzi: Climbing Mt. Kilimanjaro

I drink so much water during the day that midnight trips to the outhouse (bring toilet paper) are inevitable, but at least I’m rewarded by the clearest night sky I’ve ever seen.

The mountain rises in two volcanic peaks: a smaller one called Mawenzi (17,564 feet, 5,354 m), which is rocky, pointed and resembles the Matterhorn, and Kibo, the giant, glacier-capped volcanic flattop.

The third night we camp at the base of Mawenzi, and waking up to another dusting of snow on the craggy peak definitely reminds me of the Swiss Alps.

On the fourth day, we trek what’s known as the Saddle, a long stretch of alpine desert between these two summits, covered in hard sand and small rocks.

By now, we’re at about 13,000 feet (3,962 m). The wind whips over us as we creep across. The desert seems to stretch forever in every direction, and the only real landmarks are jagged Mawenzi behind us and the dark-brown camel hump of Kibo.

Now dead ahead, so close that we can clearly see the glaciers that crown the top.

Kobo: Mt. Kilimanjaro

The trail is essentially flat at this point, but the direct sun and wind make it a battle against the elements. Sun block and lip balm are critical, along with a constant supply of water.

Throughout the trip, I’ve been rationed sugar products — chocolate, juice and biscuits — and the extra energy comes in handy. At the end of the day, we camp at the base of Kibo, all visibly anxious, knowing that the most challenging stretch is only a few hours away.

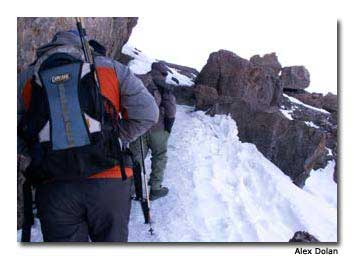

I’m wearing every layer I’ve brought, and should have thrown on a second layer of thermal socks. But after a grueling six-hour climb in the dark, a ripe red sun rises over Mawenzi and warms us instantly.

We see how far we’ve climbed during the night — a viciously steep slope up to Gillman’s Point at the rim of the volcanic crater.

From here, we get a closer view of the glaciers that rise a few hundred feet from the scree, giant white walls out of the brown.Today is summit day.

This is a 17-hour day. We need to start at 11 p.m. so we can arrive at the summit by dawn, and it’s freezing.

The wind lashes us, and outside the small circle of light from my headlamp, I can’t see a thing. We trudge at a slug’s pace up switchbacks as the bitter cold seeps into my gear.

After a brief rest, we traverse the rim, around the ash pit of the dormant volcano to Uhuru Peak, the highest point on Kibo.

Ironically, the final part of the climb, while much gentler than our evening hike, takes the wind out of all of us.

At the summit, we all celebrate with hugs, and savor breathtaking views from the roof of Africa. Because we’re standing at the rim of a crater, we don’t see the 360-degree panorama one might expect.

But the views of the Tanzanian plans are stunning, and the sense of accomplishment is worth all the work.

We descend along the easier Marangu Route for two days, and I can finally compare the two paths.

Marangu is less scenic than Rongai, wide enough for an automobile, and the tread marks indicate that it’s been used by many.

It’s more manicured, and dotted with wooden bridges and huts that seem like small villages.

At night, instead of taking in the stars, we overlook the brilliant city lights of Moshi (population 145,000) on the southern slope of Mount Kilimanjaro.

After the climb, we celebrate with a few beers, including a sip of home-brewed and pulpy banana beer, and pack for home.

As someone who’s been looking forward to this climb since I was around eight years old, I’m still thrilled months later.

I had envisioned the trip for years, but the actual experience was grander and more vibrant than I’d hoped.

For anyone considering the trip, this is the amateur hiker’s dream, and almost anyone who prepares for it can make it.

If You Go

The African Adventure Company

www.africa-adventure.com

Tanzania Tourist Board

www.tanzaniatouristboard.com

Tanzania High Commission London

www.tanzania-online.gov.uk

Explore-Share

Climb via the Rongai route in 7 days