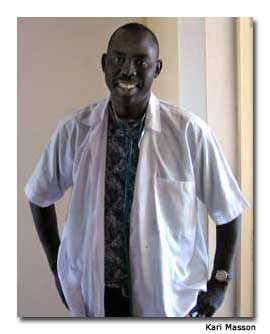

Second only to the chief, 42-year-old Daouda Mbengue is the most-respected man in his village. Although he speaks three languages and completed his medical degree in Sénégal’s capital city of Dakar, those are not what set him apart. His two wives and their sons are considered a symbol of status in his Muslim community, but that’s not why he is admired, either. What distinguishes Daouda is that he came home.

Much of Sénégal, in Western Africa, lies in the dry Sahel Desert, but the southern Casamance region has a lush and tropical climate. The capital, Dakar, lies on the Cap Vert peninsula, the westernmost point in Africa. This is the land of the Lébou, Daouda Mbengue’s people. Numbering about 300,000, the Lébou, traditionally fishermen, live along the coastal regions of Sénégal, in Mauritania, Gambia and Guinea-Bissau.

Daouda’s father and grandfathers made their livelihoods from the ocean, but commercial fishing boats slowly emptied the waters. Now, the only way for a Lébou man to make a good living is to leave the villages for the cities, just as Daouda did. His family pooled their money for him, the oldest son, to go the university in Dakar.

After earning his degree, Daouda was offered a prestigious job with the Sénégalese military. He worked in the children’s hospital of a large city and specialized in tuberculosis — a very different world than he knew growing up in the small fishing village of Sindou.

One day he received news that this village had built a clinic, but the country’s shortage of medical workers meant that there was no one to run it. Unless he returned to his village, the clinic would sit empty.

“Assalaamaalekum [Peace be upon you],” I said, greeting the man wearing a lab coat, as I took off my plastic sandals and entered the clinic. I had only been in Sénégal a few months, but already my cultural eyes had adjusted. I could see that this small, cement-block building with no water or power was a symbol of progress for the people of Sindou.

Unlike their neighbors, they now had a clinic. When malaria made its annual trek through the country, they would have a place to go for medicine. When their children fell on the jagged rocks, they could be stitched up. They had someone they could trust, one of their own who had come home to help them.

They also had me, a young American health worker who stumbled through their melodic Wolof language and didn’t know the first thing about treating malaria. But Daouda understood my greeting, and he reached out to shake my hand. “Maalekum salaam [and on you be peace],” he said, heartily.

Daouda introduced me to the clinic staff, which included Aida, the assistant, Pape, the pharmacist, and Mbaye Siny, the receptionist. Mbaye’s painful-looking twisted leg was the result of a poorly aimed immunization needle that damaged his sciatic nerve as an infant, a fact that did not escape me the day Daouda taught me to give injections and run an I.V.

I had prayed that my first patients would not be children, fat tears on their pudgy cheeks. In fact, the experience could not have been any farther from what I’d imagined.

Daouda and I walked on sand through dry baobob trees to the nearby village of Pintiure, where a woman was very sick, but her family did not have the money to have her hospitalized. We found the woman on a thin foam mat in her hut surrounded by her sisters, who were chanting and praying to Allah. (More than 90 percent of the population is Muslim.)

The woman’s name was Fatou. She was severely dehydrated, and not responding. Daouda’s resourcefulness impressed me as he strung an I.V. up to the straw roof. As I helped him, he said, in what I hoped was a joking tone, “Tomorrow you can do this by yourself. I’ll just watch.”

True to his word, the next day Daouda watched me preparing Fatou’s intravenous cocktail and then administering it during a five-hour process. My prayers had been answered: The first veins I worked on belonged to an adult who could not respond with tears or cries. Ironically, now I prayed that she would.

As we drank rounds of hot mint tea and waited, Daouda asked if I could come back tomorrow and do the same thing alone. We had been joking all day — like when I asked what to do with the used needles, and he told me to eat them to be sure the kids didn’t play with them — yet I decided not to respond sarcastically to his request for me to return solo, in case he was serious. He was.

Daouda had been forced to pick up a night shift at a hospital in the nearby town of Diamniadio to supplement his US$ 50 salary each month from the clinic, the most the village could afford to pay him. The next day he would work in the clinic in the morning, come by Pintiure to check on me in on his way to the hospital to work the night shift, then make it back to Sindou in time to work on Friday morning.

I wondered when he would find time to go home, catch a few hours of rest on his foam mattress, and eat a few handfuls of rice and fish prepared by one of his wives.

When we left that evening, Fatou had opened her eyes a few times, coughed once, and was moving her right arm. Her oldest sister tried to pay Daouda 2,000 CFA francs (US$ 4), which would cover about a third of the cost of the treatments, but Daouda refused and insisted that the money should stay in Pintiure, where many were malnourished. His selflessness and perseverance never ceased to amaze and humble me.

A few weeks later, one of the sisters in my Sénégalese host family brought her two-year-old daughter, Awa, to me. I quickly recognized the symptoms of malaria, so we took her to the clinic. Usually the clinic only closed for weekly prayers, and maybe the occasional soccer match against a rival team.

It hadn’t occurred to me that the clinic would be closed, since it was Friday afternoon and the men were praying at the mosque. Walking home, we ran into Daouda coming back from a shift at the hospital. Even after working all day and night, he opened the clinic for this little girl.

I followed Daouda into the pharmacy room when he went to get her medications. I told him that I wanted to pay the bill for Awa. He looked at me oddly, so I said again, hoping my accent would be better this time “I want to pay for it.”

He smiled, and then mimicked me exactly and said, “I want the clinic to pay for it.” To many of us, this may not seem like a lot, considering her treatment cost US$ 12, but in Sénégal that was a week’s pay.

Daouda would not let me pay, because Awa was part of my Sénégalese family. He knew that I had plenty of money to pay for the little girl’s treatment, but in his world relationships and family are the most treasured things.

The Sénégalese culture can be captured in one word: teranga, meaning hospitality. One of its many expressions is that you may be invited at any time of day or night to drink attaya, a hot and bitter green tea usually brewed and served in three rounds.

Each round takes up to an hour to prepare, and is served sweeter than the last. It symbolizes friendship, growing sweeter with time. Teranga is a way of life that treats others with kindness and respect, just as you would family.

I left Sénégal a few months later with stuffed bags, a filled heart and deep respect for a man named Daouda Mbengue, the man who came home.

If You Go

Sénégal Tourist Office

Travel and Tourism in Sénégal

www.au-senegal.com

Sénégalese Tour Guide

www.saintlouisdecouverteenglish.blogspot.com

When to Go

The best time to travel in Sénégal is between November and March, when it is fairly cool and dry.

What to Eat

Sénégal’s famous yassa ginaar is a dish made with chicken, caramelized onions and lemon juice, served over rice. You can find it on menus in fancy restaurants downtown as well as in street stalls. While yassa gets a lot of well-deserved attention, another delicious meal to try is ceebu jen. It’s not hard to find ceebu jen, as it is the meal served daily in Sénégalese homes. Smoked fish and vegetables are piled on top of rice cooked in a spicy broth, then eaten with your right hand.

Where to Go

The Île de Gorée is one of the most popular stops for visitors. An island off the coast of Dakar, it was the largest slave-trading center on the African coast, and the last stop on the slave-trade route before heading to the Americas.

A UNESCO World Heritage site since 1978, the island serves as a reminder of human exploitation and as a sanctuary for reconciliation.

In the Soumbedioune neighborhood of Dakar, there is a large artisan market offering handmade souvenirs. Bartering is half the fun. Walking away having made a new friend is the other half.

The city of Saint Louis — capital of the former French Western Africa from 1895 to 1902, and capital of Sénégal until 1958 — is in the northwestern corner of the country, at the mouth of the Sénégal River. It’s known for its colonial architecture and its annual jazz festival, and well as for being the gateway city to Djoudj Parc, a bird sanctuary about 37 miles (60 km) upstream.

If you are looking for a beach vacation, try the Saly-Portugal (or Saly-Portudal) area, about 45 miles (72 km) south of Dakar, which offers a multitude of western-run resorts with a wide variety of amenities and excursions. Shuttles from Dakar are available, and the scenic drive is a great introduction to Sénégal.