The local government unexpectedly sent Volodya, a park ranger, along on my organization’s trail-building project near Lake Baikal in Siberia — not the first last-minute surprise they’d sprung on us.

The local government unexpectedly sent Volodya, a park ranger, along on my organization’s trail-building project near Lake Baikal in Siberia — not the first last-minute surprise they’d sprung on us.

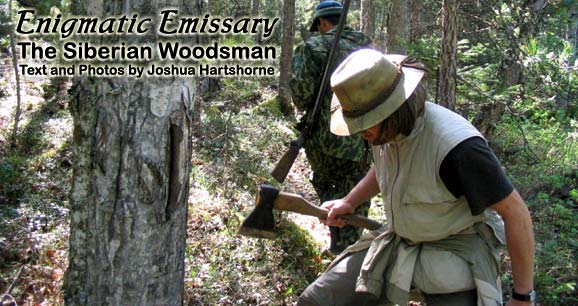

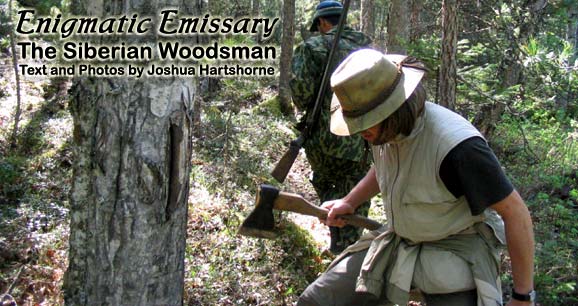

With Volodya came his taped-together double-barreled shotgun and four mangy dogs. Before knowing his name, we referred to this dark, gaunt and bestubbled man in fatigues as our “minder.” As the local representative of a government that at times seemed to treat us more like Gulag inmates than volunteers, Volodya had a fair amount of distrust directed at him. One of our crew leaders, trying to be upbeat about it, said, “He should at least add some color to camp.”

And he did.

Volodya, approximately in his 40s, spoke only a few words of English. As the project’s official translator and one of the few Russian speakers in the crew, I had the most opportunity to get to know him. Opportunity is not success, however, and Volodya’s ready and unabashed ability to contradict himself in successive sentences meant that the more I talked to him, the less I understood.

Volodya was born in Azerbaijan, a former Soviet republic north of Iran. However, he considers himself Russian, despite his olive skin. (In Russia, the word “Russian” has a racial and ethnic — not geographical or political — meaning.)

He left Azerbaijan as a teenager and has not been back in a long time, having only one remaining relative there.

After leaving home, he served in the army for a dozen years. His last army assignment was to a small team that cemented over the site of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant meltdown. Of his 15-man crew, only four are still alive. He attributes his survival to two years of heavy vodka drinking afterward.

After his wife died, Volodya sent his son and daughter to live with his sister in Krasnoyarsk. He grew unusually quiet whenever the subject of his wife came up. Krasnoyarsk is a day’s train ride away, and I have no idea how often he sees his children. A man who spends his summers deep in the wilderness cannot easily raise kids, and I cannot imagine him visiting a city, much less living in one.

Volodya is a consummate outdoorsman. A couple friends and I went on an overnight camping trip with him. He didn’t bring a sleeping bag or tent, even though the balmy summer temperatures in that part of Siberia regularly drop to freezing during the night. “What do I need those for?” he asked. “I’ll build a fire, cover myself in moss. What more do I need?”

As grizzled as he was, as much a wild man as he was, he was also an incorrigible flirt, an occupation in which he had a good deal of success. Both the women on our project seemed to find him surprisingly adorable.

At first, I did not spend a great deal of time with Volodya. Perhaps even more than the others, I viewed him with not a little suspicion, not really knowing why he was with us, and not trusting his employers. It was only during the overnight camping trip toward the end of the project that I had time to really get to know him. I was surprised about what I learned.

The first surprise was that Volodya was in full favor of our organization’s goals, which is to bring more tourists to Baikal. I had not expected a man used to living alone in the wilds to want more tourists trampling through his backyard. “Maybe there will be lots of tourists near Irkutsk and Listvyanka,” he explained. “But Baikal is big. There will always be plenty of empty space.”

He sees tourism as the solution to the area’s problems. “The region is poor and needs to develop economically,” he explained. He also thought more tourists would mean fewer poachers, his main enemy as a park ranger. A better economy would mean fewer reasons to poach.

He hoped that many poachers might choose, instead, to be wildlife guides, bringing tourists to shoot pictures, rather than bullets. Finally, he noted that tourists tend to scare off poachers. I was surprised to hear all the arguments we in the city use to pitch our projects from a man who lives in a shack in the woods.

Where he truly won my gratitude was by making sure I could eat dinner. The cooks on the project didn’t seem to respect my dietary needs, and more than once I faced a long day of backbreaking work without lunch.

“Of course I’m not going to cook something you can’t eat,” Volodya said. “If you go hungry, you aren’t going to be happy, and my job is to make sure my tourists are happy. I want you to go back home and tell people what a wonderful time you had here. That’s how we get more tourists.”

Volodya, a backcountry ranger, knew far more about how to run a tourism business than his boss, the head of the Department of Tourism for the region, who clearly cared not a whit whether we enjoyed ourselves. His idea had been to make us work from dawn to dusk … quite a proposition near the Arctic Circle in summer.

There was one thing that Volodya simply would not tolerate, however much it angered his tourists: People were not to go out and about alone. When Jon, one of my friends, went on a hike alone through the woods, Volodya was furious. For his part, Jon didn’t think Volodya had any right to tell him where he could or could not go on public land. Jon found Volodya’s insistence that the woods were “too dangerous” insulting.

Now on good terms with Volodya, I decided to talk to him about it. It turned out that his main concern was liability. He was legally liable for our safety while there.

“I have two children to support. I can’t go to jail,” he said. He was reasonably skeptical as to whether Americans who’d never camped in Siberia were really up to the challenge, whatever experience they had from back home.

He himself had been to Alaska, and found it tame compared to the Russian taiga. However, if tourists signed forms saying they took full responsibility for their own safety, he didn’t see any problem with them wandering about (and possibly getting eaten by bears).

While there were still subtle points of disagreement, Volodya and I agreed that if the decisions were left up to the two of us, we could find a common ground. I explained all this to Jon, who was soothed.

As we were sailing away, everyone was waving goodbye to Volodya. Jon said to me, “You know, Volodya wasn’t such a bad guy.”

If You Go

Lake Baikal Center of Adventure Travel

www.baikal.eastsib

Russia Information and Destination Guide

www.russia.com