It’s 5 a.m. on December 31, and Puno, a lakeside town in southeast Peru, is stirring. Coral pinks and tropical aquamarines creep into the sky. I gaze up at the rafters, tied with strips of llama skin.

Celebrating the New Year in Peru

Closely following the dawn chorus of birds come the cries of children playing an impromptu soccer game by the railroad tracks. I watch them through the window. The game includes children of all ages, and the small children are swooped out of the action zone when the game moves their way.

The one-room dwellings where many of these families live aren’t big enough for playing inside, so the kids are outside as soon as it is light.

The traders, too, are already arriving and setting up their stalls on the sidewalk, first laying down the cerise and blue woven cloths that serve women as baby slings, backpacks and, now, a cloth on which to arrange trinkets.

We bartered with the vendors yesterday to buy yellow underwear, which we plan to wear at midnight tonight — a Peruvian tradition said to bring good luck for the New Year.

Before we start on the day’s adventures, we enter the dining room to find a table spread with red and orange cloths. The smiling staff of our hotel has prepared a cornucopia of breakfast foods: quinoa, oatmeal, maca, or wheat porridge, fresh mangoes, papaya juice, bananas, oranges, crusty white rolls, strawberry jam and strawberry yogurt. Tea in hand, I gaze through the picture window at the distant mountains across the lake.

We leave the hotel in a private combi, a tour bus, to go up the mountain and visit the chullpas of Sillustani, pre-Incan funeral towers high above Lake Umayo. The chullpas were made of immense granite blocks, shaped into cylindrical forms that rise as high as 39 feet (12 m). It’s astonishing to see these jigsaw-puzzle structures in which massive stones were fitted together without the benefit of modern lifting equipment.

The scenery is akin to that of my native Pennine Mountains in Britain, albeit on a much larger scale. Purple heather blooms, and tufts of moorland grass, bleached at the tips, wave in the slight breeze. Alpacas graze alongside sheep, and are accompanied by shepherds holding large crooks.

It’s easy to indulge the fantasy of being lost in time and space, of being back in a purely agricultural society. When we give an eight-year-old shepherdess some fresh fruit, she tells us her name is Vanessa. To me, the highlands seem like a great place for meditation, but I can’t imagine any children I know being content to be so alone with the sky, the mountain spirits and the beasts. I wonder what Vanessa thinks of all day long as she watches the herd.

The view is spectacular; you only have to turn a few degrees to see a different panorama. The air is so clear that you can see for miles to distant peaks, and the gently moving clouds throw shadows on the mountains as though trying out different garments.

The ancestors of the indigenous people here buried their dead high in the mountains, in caves on inaccessible peaks. They believed that the dead would be closer to the spirit of the mountain that way. Families used to visit the graves once a year, bearing food and gifts.

We bring gifts to the living, handing out chalk, pens, flashlights, candy, fruit and sunscreen to kids who have few material goods. In return, they pose for photographs. The cute little girls know that if they clutch a lamb and gaze winsomely at us, we’ll surely take their photograph and give them a few coins. Even if they have never heard of Little Bo Peep, the pose of shepherdess comes naturally to them. They hug the lambs and cradle them as though they were dolls.

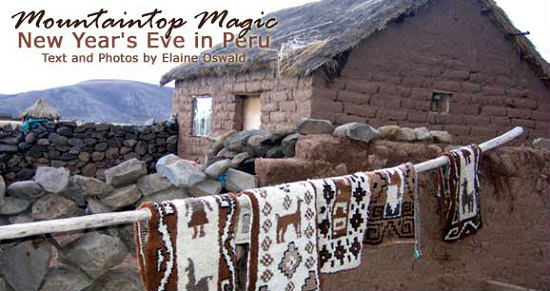

On the way down the mountain, our tour guide stops at a shepherd’s compound, which consists of two one-room dwellings linked by a fireplace and surrounded by a wall. The living quarters are low, small, and dark: One for his daughter and her family and one for him, his wife and two boys. The homes are built of dried mud blocks. They remind me of the wattle-and-daub cottages of medieval England.

The only light is from a strip of llama skin that has been coated in tallow, like the wick of a giant candle, dangling from the ceiling. One side of the hut is taken up with a bed in which the family sleeps. The other has a loom, and pieces of fabric and rugs made from llama wool, which the shepherd works on while there is light. His wife’s communion and bridal shawl hangs there on the wall, a finely embroidered piece that looks incongruous in this smoky setting. The shepherd has also hung up his daughter’s school certificates; it’s the family parlor, with treasures on display.

After the shepherd has demonstrated his deadly accuracy with a slingshot and a rock that could kill a person as well as marauding pumas, he offers us a snack, a wheel of creamy llama cheese looks like Brie but has a chalky texture. This is accompanied by homegrown potatoes, small and knobbly, from the rocky ground. If there’s one thing Peru does well, it’s potatoes — there are hundreds of varieties.

After the repast, the shepherd, who is also a shaman, offers us some gray clay that’s supposed to help with digestion, and then prepares a New Year’s Eve spell for us. He burns herbs and ground powders in a handmade bowl and makes sure we each inhale the fragrance and immerse ourselves in the smoke. He asks where we’re from, and sends blessings bouncing back to Tennessee for my husband and me, Lima for our son, and Scotland for our daughter.

I buy a rug from the shaman-shepherd; it reminds me of the ones my grandmother used to make. My new llama rug is beige, brown, and black, the natural colors of the llamas, and it won’t go with my color scheme. Yet, it means more to me than mass-produced ones, since I know that this shepherd has clipped the wool (which is done only every two years), spun it and woven it into a rug. It retains the smoky smell of his house.

The view from the man’s mountain hut is as fine as anywhere in Peru. The concept that the dead are looking down on us not from an intangible heaven, but from a cave in the mountains, is an idea that I like; it makes me feel very close to my late father and grandmother. It’s a fitting end to an old year, and a perfect welcoming of all that is to come in the New Year.