Modica is among the towns of southeast Sicily that was devastated by an earthquake in 1693. Its good fortune was to be rebuilt during the late Baroque period, yielding a phenomenal architectural heritage. The challenge today is getting to all the churches and palaces, since they are linked by a maze of steep slopes and stairs. What keeps me going is my admiration for all the craftsmanship and, of course, the delicious rewards along the way.

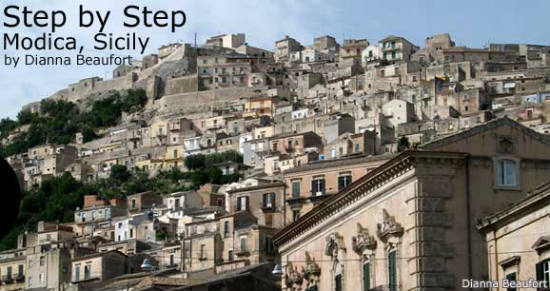

Modica has clung to its valley walls since Neolithic times. Its mountainous geography, amid the Iblei Mountains in southeastern Sicily, meant that when rebuilding the town in the 18th century, city planners had to diverge from the ideal Baroque town plan, a grid plan dotted with piazzas. Instead, the new buildings were spread over the upper (Alta) and lower (Bassa) parts of town, making for a very picturesque townscape. In the process, attention was lavished on individual architectural expression.

The Cathedral of San Giorgio is the ultimate in religious architectural expression. As I approach from Modica Bassa and climb the 250 steps to Modica Alta, the church’s facade soars upward in front of me. Despite the stairs, I am like a bee to honey, mesmerized by its honey-colored stone and intricate carvings.

The climb is interrupted by a road (the main road zigzagging down toward Bassa), and the pause gives me a moment to take in the full effect of San Giorgio’s 18th century opulence. The undulating lines of its façade make the cathedral seem to pulsate. Its sculptural mass culminates in an open stonework belfry, a feature characteristic of Sicilian Baroque. The splendor of the church’s exterior is matched inside by swirling gold and pastel embellishments.

Looping around the back of San Giorgio and through a warren of steep and tiny streets, I ascend farther into Alta, to Modica’s highest point, the Castle of the Counts. The medieval castle was built by the counts who ruled the region. Reduced to ruins after the earthquake and abandoned, it was topped off with a giant clock in the 18th century.

The climb is worth it for the best full-circle views of the Lego-like housing blocks clinging to the surrounding slopes and punctuated intermittently by Baroque outbursts. Corso Umberto I, a boulevard below that’s flanked by shops and businesses, was once the setting of a river. After the flood of 1902, the river was paved over and bridges striped away to expand and further urbanize Modica Bassa.

The boulevard is where the traditional Italian evening stroll, known as the passegiatta, takes place. Dressed to the nines, with extended family in tow and posing at the gelateria (ice cream shop) is what a Saturday night is all about here. Trattorias (snack shops) also serve the crowds, and the ones in Modica make a particular local specialty: scacce, a light pastry dough, folded over ingredients such as tomato sauce and eggplant. It’s tasty and an excellent energy boost.

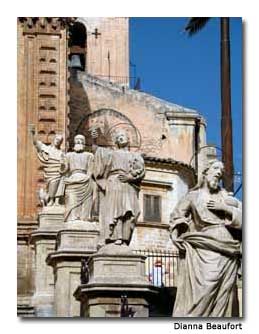

Even on Bassa streets, there’s climbing to be done. Supported by a typically Baroque flight of stairs, the church of San Pietro is one of the finest buildings lining the boulevard. The 12 aspostles flank the stairs rising to the entrance. The interior is even more striking than San Giorgio’s, with its gold work, luminescent whites and bold, royal blue accents.

The churches of San Pietro and San Giorgio not only compete in magnificence, but the two congregations have for centuries rivaled to claim their saint as Modica’s official patron saint. (Each town in Italy names and honors a special saintly protector.)

Around the time of the earthquake, San Pietro’s community was lobbying with some success for Saint Peter, until San Giorgio’s priest asserted Saint George’s superiority, and promptly excommunicated the community that thought otherwise.

While both communities learned to live with the differences of opinion, certain buildings in Modica Alta were etched with the words: Limite delle due Matrici, meaning community limits. The annual saint’s day parades required a strict separation of communities to avoid skirmishes.

Modica was a powerful political and religious base during the Baroque period, making it an attractive source of artistic patronage. The numerous churches and monasteries, nearly all restored and well maintained, are a contrast to the many urban villas in shambles along the sloping streets of Alta. Despite their state, empty and forlorn, the abandoned palazzi are signposted with their century of origin and original patron.

In the 15th century, the Cabrera family was among the wealthiest. Their personal wealth made Modica the richest city of southeastern Sicily.

They owned land in South America, which ensured an early import of the cacao bean to Modica. Directly from Aztec recipes to the Modican kitchen, chocolate was brought here and used to make a specialty of the region. Besides being used in delicious, albeit grainy, chocolate bars, cacao is mixed with minced meat to form a turnover-like pastry called mpanatigghi that melts away like mousse in the mouth.

The local cheese, caciocavallo, is a much less subtle tasting experience. I came to call it “squeaky cheese” because of its squeakiness when chewed. Its taste ranges from creamy to peppery. The cheese is served as an anti pasto (appetizer) in restaurants here.

Most restaurants in Modica are home-style kitchens. This is particularly true of Modica Alta, which is less commercial than Bassa, and more residential. The tables at Hosteria San Benedetto, a small restaurant, have a view of the family dining room next to the kitchen.

In my conversational Italian I comment on how beautiful Modica is to the chef’s elderly mother, who’s seated at the family table.

She nods and agrees, “It’s a paradiso, except for all the steps.”

If You Go

Sicily Tourism

www.sicilytourist.net

Italian Tourist Board

- Fiddle, Flutes & Pubs: A Musical Journey Through Northern Ireland & County Donegal - July 14, 2025

- Tokyo vs. Osaka: The Ultimate Face-Off for First-Time Visitors to Japan - July 14, 2025

- When Is the Best Time to Visit Iceland? Find Your Perfect Month for Budget, Weather, and Activities - July 14, 2025