“Uh, no, Carl, I’m gonna hitch.”

Backpacking alone allows one the freedom to blurt things out before your brain can stop it. After months of crisscrossing Asia on everything from boats to goats, I found myself at Niah Caves National Park — one of Earth’s largest cave systems — on the Malaysian part of the island of Borneo. Millions of bats reside here during the day and an equal number of swallows at night, give or take a few hundred thousand. A snazzy hostel tucks into the rainforest nearby.

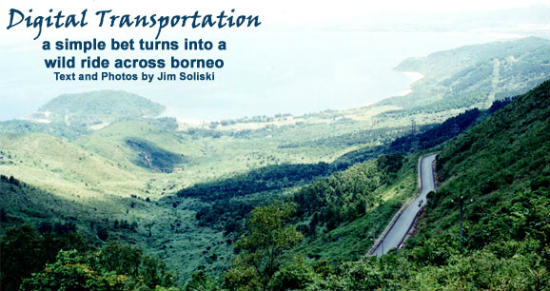

“Go West, Young Man,” wasn’t a common phrase in this rustic little hideaway, except to Carl, another traveler staying there, and myself. Since we were both heading to Kuching, the most westerly city of consequence in East Malaysia, 500-plus miles (800 km) away, he suggested that we team up. A bus to Sibu and then a high-speed ferry to Kuching would shuttle us in early the next morning. Carl wasn’t a lout, but I just couldn’t bear the thought of his voice and the hiss of public bus tires simultaneously.

“You’re gonna hitchhike?” he asked.

“Uh huh, and I’ll get there before you.”

“You’ll take a week, or die.”

Could be.

Shortly after 8 a.m. the next morning, I hung out an ambivalent thumb, without Carl, and within 90 seconds a car stopped and took me to the main highway, putting me 20 miles (32 km) ahead of Carl. His bus wouldn’t depart for another hour. My driver drove left, I walked right, and the next car took me about 12 miles (19 km).

Then, I waited 10 minutes or so for an eventual 30-mile (48 km) ride. After 10 minutes, my rested thumb pulled out a plum. Two lovely Malay women, late 20s, were headed to Bintulu, which was the end of my arbitrary first leg and point of departure for the second, the trip to Sibu.

“What was I doing begging rides on the highway?” they wanted to know. Westerners were not poor Malays, or conservative Muslims, and their fates might hang heavily on the minds of Malays. When I explained about the race, they giggled, and we settled back as friends on a journey where decorum gave way for speed. About 5 miles (8 km) from Bintulu, we slowed suddenly before a highway sign that said, “SIBU, NEXT LEFT.” Throughout the lift, their friendliness had me dreaming of Malaysian hugs and kisses under palm trees, but reality dropped a coconut. Doing a maybe and hitting a dead end was an unwanted alternative to fantasy cuddling, so I confessed the desire for my Kuching rather than their Bintulu and unloaded. The race was getting pricey.

The highway at the crossroad was busy, but unripe for rides. After a long 20 minutes of standing between the road and a quarry, and after I had been punished for my fantasies by being pelted with sand, someone stopped for a mere 2 miles (3.2 km). Another 20 minutes of burnt-up daylight, and I netted a 30-mile (48 km) lift, just as I wavered between racing and plain arriving.

The traffic was thin, and a light rain had started to fall. I was fishing for my poncho when a car coming from the wrong way suddenly slowed, U-turned on the highway, the window rolled down, and a smiling face invited me aboard. Why was he stopping and turning from the opposite direction?

In the car, the man explained that he had passed by a few minutes earlier, then had an attack of conscience and couldn’t leave me outside in the rain. He was a Malaysian-Chinese businessman in the logging industry, educated in England, spoke excellent English, was very bright, and en route to Sibu. We shared our experiences with travel abroad and with crowds of lovely lady drivers, and we asked and answered each other’s questions during terrific conversations. He was so interesting, the race had become a non-starter. In fact, I never mentioned it. He adamantly insisted on paying for lunch, a toothsome bowl of noodle soup, claiming “Malaysian hospitality.”

In Sibu he dropped me at a ferry. On the boat, a Chinese couple candidly told me the idea of hitching was nuts, and that racing was, well, not too swift — but what the heck, they said, come on with us. An hour later, on the highway again, and using my ever-lengthening shadow as a sundial, the sun set slowly and my reservations rose. I needed a long-haul transport truck. No sooner did this thought insert and extract when two young fellows running empty from Sibu to Kuching rumble up. They cleared the rear sleeping area, offered whatever they had from cigarettes to mineral water, referred to me as “Sir,” and drove that lorry like they’d stolen it.

An hour and a half out of Kuching, the sky pitch black, the front tire blew. My guys, cursing in Malay, kicked the spare out of its hiding spot. Flat. They used one of the dual rear tires — the nuts were too tight, rusted on. They called the office on the cellular — no answer.

We had broken down in front of an army base: half the National Guard stood around looking for a solution and puzzling who the hell the white guy was. I queried, while slapping mosquitoes, whether the military wouldn’t have the tools to do the job.

“Of course, but that would be government property and off limits for Malay citizens.”

My chauffeurs were totally race-minded, and to my complete surprise they decided to flag down a bus for their competition-minded friend. They would sleep in their truck until help could come the next morning.

The night gets inky black at the equator, and even with a three-quarter moon, it was still too dark for bus drivers to see our waving in time. The army boys weren’t missing out on this; they came to life and launched a roadblock. Five or six attempts to secure a Kuching-bound vehicle begat no success and a lot of laughing, splattered soldiers. Finally, a family of Chinese-Malaysians riding in an SUV agreed to an extra passenger. I thanked the revived military, blessed the Chinese, and embraced my helmsmen, offering to buy the latter a beer of gratitude the next day if we could get together.

Beginning at the outskirts of Kuching, my latest driver initiated high-level discussions about suitable accommodations. Generally, most Asians expect that any tourist wants snazzy digs on holiday. I was difficult. Their picture of the white race had no room for hitchhiking Canadians with thin wallets, but I finally managed to convince my new friends to think cheap. They dropped the name of one establishment, a name that I recognized as the first choice suggested in the Fat-Cat’s guidebook. Standing on the sidewalk outside choice number one, in full diplomatic mode, I thanked them for their assistance and advice, and waved with real gratitude as they roared away.

The hotel was expensive, but fortunately it was also full so I didn’t have to face the decision to part with my limited funds. I went to another across the street — still too much. Went to another — locked up tighter than a bank vault. Went to another — no vacancy at any price. Then I remembered that I was in Asia, where the expensive is offered to the visitor before the cheap is even remembered. Returned to the expensive hostelry; they magically produced the heretofore nonexistent cheaper room, and I was in Kuching for real. Suddenly, I remembered the race, and thought wistfully that win or lose, it was over.

Past 11 p.m. by now, my eyes felt tired, itchy from sand and wind, and the lids were heavy; I skimmed an old newspaper I found in my lair, and turned off the light. Laying in the dark, I imagined Carl still in Sibu setting his alarm to catch his morning high-speed ferry. I fell asleep realizing that in a whirling storm of sand and rain, Chinese and Malays, teamsters and troopers, strange men and fascinating women, my race had been won. I closed my weary eyes and slept the sleep of the surprised, contented, and freshly informed.

If You Go

Tourism Malaysia

- Exploring the Culture and History in Fascinating Astana, Kazakhstan - July 24, 2024

- Breakers & Beyond: Top 10 Things To Do in Newport, Rhode Island - July 23, 2024

- Laid-Back Lombok: Coconut, Coffee and Coral Reefs - July 22, 2024