Bumping across the open fields, the noisy old jeep sends huge flocks of birds and dust flying. When the brush becomes too thick, it’s trekking time. There is no trail on the sandstone formations and open fields, just termite mounds and thick brush.

Max Davidson stops and waves an arm across the expanse of scrub landscape peppered with rocks.

“To you this looks like a barren place. To the Aboriginals, it is a giant supermarket and hardware store,” says Max.

Aboriginal hunter-gatherers have survived among these rocks and woodlands for 50,000 years. Past experiences have made them wary of white men. Max is one of the few they trust.

“Yep, I’m white on the outside and black on the inside. I love their life,” says Max, who has a perennial twinkle in his eye and only needs a red suit to be a dead ringer for Santa Claus.

He met Charlie, the owner of this land, when he was a jackeroo (Australian cowboy) in New South Wales. Charlie considers Max his brother.

“I have been accepted by him,” says Max. “That means I help him with whatever he needs.”

About 35 years ago, Davidson came to the top end of Australia’s Northern Territories to hunt buffalo. He instantly fell in love with Arnhemland, Charlie’s ancestral lands. He leased some of it and built a safari camp.

“There is no other place I want to be,” he says.

During the wet season, most of the area is covered with water. In the dry season water is replaced with dust. Whatever the season, there are the birds, over 200 different species of them.

Davidson delights in acquainting his visitors with the area’s huge expanses of freshwater billabongs (dried riverbed waterholes) rainforests, sandstone formations, termite mounds, desert woodlands and art-filled caves. Every trek is a learning experience.

During our visit, Charlie and his friend, John Cooper, are at the camp. Although they will not speak directly to us, we learn from them.

Everyday begins the same way. At exactly 6:30 a.m., kookaburras come squawking over the camp, making sure everyone gets an early start.

“Today is the important day,” Max announces at breakfast.

While flying over the area, Max discovered an arrangement of stones. We will hike to the site with Charlie and John Cooper.

The trek is a rock scramble through the bush. At the top of one ridge, there are stone circles. Others delineate a path for as far as the eye can see. Charlie examines the circles, sits down and stares out into the serene landscape. He finally turns to John Cooper and Max. Max is the only white person with whom he will discuss anything. That is the Aboriginal way.

We watch from a distance noting the seriousness of the conversation. Max later reveals that Charlie knew of this spot from his father and grandfather. It is a several hundred year-old morac, a sacred, ceremonial site. To have discovered it at the same time Charlie did is a privilege.

There are other special times. On the hardware/grocery store day, Max demonstrates how plants are used for food, medicine, paintbrushes and containers. Eucalyptus is used as antiseptic, spot remover and drink. Rock fig bark is rolled into string.

We feast on the hearts of palm from the cabbage palm, and examine wheat-like spinifex, which becomes bread when baked. The Aboriginal bread maker is a hollowed out, fireproof, termite mound.

On the way back to camp, a swarm of green ants zealously come to bid us farewell.

“Taste them,” says Max. “They are Aboriginal candy and a cure for colds.”

I demure, preferring sweets that do not crawl down my throat.

Later, in the middle of the vast plain, Sid, Max’s assistant, stops the jeep for wine and nibbles. A dingo and a wild pig watch our happy hour from a distance. Thousands of magpie geese, eagles, whistling ducks, egret, darter birds and brolgas loom like giant clouds, silhouetted against the enormous descending fireball of a setting sun. The jeep returns to camp in darkness.

“Today is a major art day,” says Max of our next adventure.

The jeep bounces along the unending expanses on the way to ancient art galleries. We trek deep into the bush. Again there is no trail, but Sid knows the way up ridges, over rocks and into caves.

We explore a cavern that was once a refuge for buffalo hunters. A painting of an old sailing ship, painted with the letters “H.M.S.,” and an old, rusty Martini-Henry gun, protruding from a ledge near the ceiling, authenticate that the 19th century presence of the British.

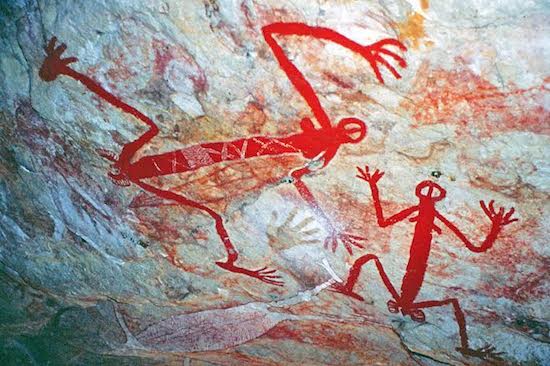

We move on to more ancient archives. Cave ceilings and walls are giant easels covered with animal and spirit art. Drawings are painted one on top of the other, because the Aboriginals believe that gives their paintings more power. Kangaroos, turtles, fish, wallabies, spirits and giant serpents cling to the walls. Many are Aboriginal dreamtime stories; stories about creation, laws and how to survive in the harsh environment. Some say the grass stroke paintings are 50,000 years old. Others are said to be 15,000 years old.

“No one except the person who painted it knows what it really means,” says Sid.

Like us, Sid is on a path of discovery. Half white, half Aboriginal, he is a member of the “Stolen Generation.” Max is helping him to find himself in the land and traditions of Aboriginals.

Sid leads us to a cave that is completely covered with red hued, hematite handprints. The ceiling ledges are filled paper barked-wrapped human bones. Bats fly in and out. With his hands, Sid vigorously rolls a stick, the sharp end of it stuck in an indentation of another stick attempting to start a fire the Aboriginal way. We sit silently in this timeless, surreal setting for about 45 minutes

The rest of the day is spent on the billabong, fishing for barramundi. Twenty-foot crocs eye our boat as it cruises down the water. Their jaws have the power to crush 2,000 pounds per square inch. All around us, thousands of birds cackle and flap their wings. Jacana or “Jesus birds” scurry across the pink and white lilies that float on the water.

We drop our lines and wait. After quite a fight, one of the group lands a barramundi.

Night comes quickly. Sid maneuvers the boat down the billabong. The watery path of the boat lamp reflects the eerie glow of crocodile eyes. Finally we pull out, get into the jeep and make our way back down the dark, rutted non-road.

That night, from the far end of the dinner table we here what sounds like a horde of cicadas. It is Charlie teaching Sid to play the didgeridoo, the long hollow-piped, Aboriginal instrument. After a while, the odd sound of becomes haunting. It is like the land and the people that inhabit it and have survived here for so many thousands of years.

If You Go

Davidson’s Arnhemland Safari Camp is accessible by car or by air charter from Darwin. Three, four and five-day packages are dependent on group size, but include the air fair, lodging, food, tours and taxes.

For more information visit Arnhemland Safaris.