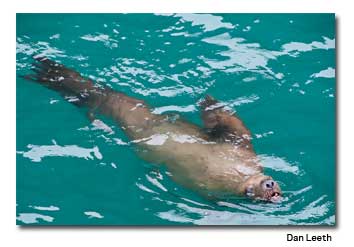

It smells like a back alley behind a third-world bar, but nobody on board our tiny ship seems to mind. The aroma emanates from the guano of some 6,000 nesting pairs of black-legged kittiwakes. These 16-inch gulls with 36-inch wingspans call the fjord-hugging rocks home.Our vessel idles offshore, just beyond the mist of twin waterfalls pounding into the sea. These torrents of rumbling white plummet from peak-clinging snowfields and hanging glaciers far above.Over the din of squawking birds and pummeling water, I barely hear the amplified voice of naturalist Kate Caldwell as she points out a flying pair of tufted puffins, a soaring bald eagle and a backstroke-swimming sea otter.Which is more impressive, I ponder: the Disney-like wildlife encounters or the encompassing, IMAX-worthy landscape? Both promise to be abundant on this cruise around Alaska’s Prince William Sound.

It smells like a back alley behind a third-world bar, but nobody on board our tiny ship seems to mind. The aroma emanates from the guano of some 6,000 nesting pairs of black-legged kittiwakes. These 16-inch gulls with 36-inch wingspans call the fjord-hugging rocks home.Our vessel idles offshore, just beyond the mist of twin waterfalls pounding into the sea. These torrents of rumbling white plummet from peak-clinging snowfields and hanging glaciers far above.Over the din of squawking birds and pummeling water, I barely hear the amplified voice of naturalist Kate Caldwell as she points out a flying pair of tufted puffins, a soaring bald eagle and a backstroke-swimming sea otter.Which is more impressive, I ponder: the Disney-like wildlife encounters or the encompassing, IMAX-worthy landscape? Both promise to be abundant on this cruise around Alaska’s Prince William Sound.

Compared to the usual floating resorts that ply the Alaskan coast, this 78-passenger ship feels like a boutique bed and breakfast. It offers no casino, no showroom, no swimming pool, no private balconies and no reason to gussy up for dinner.

Flexible itineraries allow time to find and follow wildlife, and because the vessel is compact, it can go where the big guys can’t. One such place is Blackstone Bay.

We reach the head of the fjord after dinner. Six separate glaciers loom here, with the largest, Blackstone, terminating a few hundred yards from the ship. This towering funnel of blue-tinged ice offers a 30-story frontal facade extending over a mile across. Conical seracs and fractured crevasses give character to its convoluted countenance.

Every few minutes, blocks the size of small houses calve from the icy face and plunge into the sea. With each chunking comes the explosive boom of a summer thunderstorm.

“They call it white thunder,” Kate says.

Morning finds us in College Fjord, a 20-mile-long slot holding more than a dozen glaciers. Most bear the names of schools. Traditional women’s colleges like Vassar, Smith and Bryn Mawr occupy one side of the fjord. Former men-only schools such as Harvard, Dartmouth and Yale stretch down the other.

“Nearly all of the male college glaciers are receding,” Kate says with a grin. “Most of those named for women’s schools remain stable.”

At the head of the fjord lies Harvard Glacier. It’s wider, but not as high and angled as the Blackstone. While most of its face appears marbled with chocolate-colored dirt, a vertical channel of clean white ice splits its center. It looks like the cream filling in an Oreo cookie.

From College Fjord, our route takes us down the sound to Esther Passage, a channel so narrow in places that a quarterback from one of those glacier-named schools could pass a football and hit land on either side. In the thick forest of western hemlock and Sitka spruce that borders the waterway, we spot eagles and a nest with a chick in it. Fish leap from the water. Sea otters peacefully glide on their backs.

Near the exit of Esther Passage, the ship picks up “Oyster” Dave Sczawinski. The Alaska-style hermit, who lives here year-round on a barge raising oysters, can go from November to March without seeing another human being.

“I love living here,” he says. “It’s a beautiful place. I thought it was going to be hard. Now it’s hard going into town.”

That evening we sail north toward Columbia Glacier. Near its terminal moraine, now seven miles from the glacier’s foot, the Spirit of Columbia can go no farther. The channel ahead looks like a giant ice bucket. On a March evening in 1989, similar icebergs from this glacier caused a giant oil tanker to change course and ultimately split open on a reef. Until eclipsed by BP’s recent fiasco, the wreck of the Exxon Valdez released the largest oil spill in U.S. history.

Cordova, one of the communities most affected by the disaster, is our only shore stop. This fishing town of about 2,300 people can be reached by air, sea or foot. The prize catch here is Copper River salmon. I ask Kristin Carpenter, a fisherman’s wife, what makes this fish so special.

“The river is about 300 miles long, and salmon stop eating when they go from salt water to fresh,” she explains. “They’re evolutionally adapted to build reserves for the long trip. That’s what makes them taste so good and be so rich in omega-3 fatty acids.”

Downtown Cordova’s business district is one street wide and a few blocks long with neither jewelry store nor T-shirt emporium to be seen. At the Ilanka Cultural Center, children representing Alaska’s first people chant and dance, while representatives from the center talk about indigenous art. In addition to native crafts, the center displays a Tlingit-crafted shame pole – a totem-like pillar designed to ridicule a wrongdoing. This one dishonors Exxon, with the inverted head of the company’s CEO spewing oil and the words, “We will make you whole.”

“The oil spill was really devastating to Cordova,” explains director LaRue Barnes. “It made a lot of people change their lifestyles. Some never recovered emotionally.”

Although the crude oil never touched Cordova, it did ground the local fishing economy for some time. Now, decades later, things have improved. The herring are still gone, but the salmon and most of the bird and mammal communities have recovered. In the distant wake of the once-oily slick, we’ve seen Steller sea lions, followed orcas, paralleled humpbacks and raced Dall’s porpoises.

That evening, we pull into Simpson Bay. The air is still, the water clear and the mountainsides dark and green. Beside a grassy, beachside stream, a brown bear teaches her cub how to pluck dinner from the water. Off in the distance, an eagle screeches, a loon cries and a wolf howls.

“The advantage of small boat cruising is that we’re able to stop and take time,” Kate says. “I think that’s what makes it so appealing.”

The ship continues into Whale Bay looking for more wildlife. Here, peaks reach into a gray sky, their forest-clad summits hugged by cotton-candy clouds. Waterfalls drape hillsides. Streams enter the ocean along sedge-covered beaches. An eagle sits atop a rock, watching.

“You get a sense of remoteness in Southeast Alaska’s Inside Passage, but it comes in bits and pieces,” Kate says. “This is even more remote. When you see other ships you feel like you’re being intruded upon because you’ve had this whole place to yourself.”

Not surprisingly, that night we share the massive Chenega Glacier with no one. Its frozen face presents a blue wall of ice stretching a full 1½ miles across. The captain apologizes for not approaching closer, but he doesn’t want to disturb the hundreds of harbor seal moms floating with their pups on chunks of ice between us and the glacial front.

I look at the seals. I look at the glacier. It’s but another Disney-like wildlife encounter in an encompassing, IMAX-worthy landscape.

If You Go

The trip described here was with Cruise West, a company that has since gone out of business.

Discovery Voyages (800-324-7602, discoveryvoyages.com) offers cruises on a 12-passenger vessel covering a similar itinerary.

For other small ship Alaska cruises, go to the Alaska Travel Industry Association website (travelalaska.com) for information about small ship cruise lines offering Prince William Sound itineraries.

Dan Leeth is a freelance writer who lives in Aurora, Colorado. Check out his website, lookingfortheworld.com.