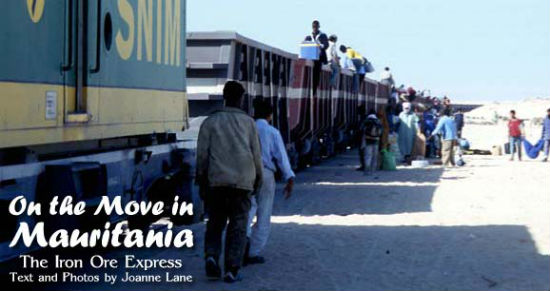

You can’t see it, but somewhere in the approaching sand cloud is one of the longest trains in the world: It’s one-and-a-half miles (2.5 km) long. It’s impossible to discern anything in the jostle of passengers and the rasping dust the train has kicked up as it rolls toward us through the Sahara Desert.

The freight cars pass for what seems an eternity, the train gradually slowing until, at last, with a shuddering halt, the two passenger carriages reach the station of Nouadhibou, formerly Port Etienne, with a population of 90,000, Mauritania’s second-largest city and commercial center.

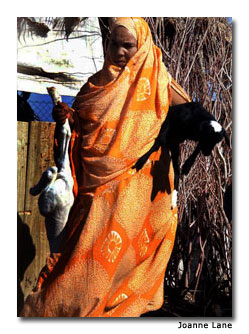

Those who have not yet jumped into the passing freight cars stake their claim on the last of them, while the others mass outside the passenger carriages. There are men in turbans, women in billowing dresses, young children, enormous bundles, rugs, bleating goats and enough pushing and shoving for a rock concert. They all want to board at the same time — through the same door.

I make the mistake of stepping back to take photographs. I escape the bedlam and am hopelessly shunted to the end of the line. It soon becomes clear that many of these people are not embarking. They are husbands, family or friends assisting others in getting on, but inadvertently adding to the confusion. And I cannot get past them.

They also have every reason to panic — the train only stops for a few minutes. A woman in a pink dress finally hauls me into the carriage by seizing my backpack, while her husband pushes me by my buttocks from behind. Just as I am launched inside, the train lurches violently and we plod off into the heart of the Sahara.

The Iron Ore Express shuttles people and ore from the desert to the coast on a single-track railway line of 419 miles (674 km).

The ore is the bedrock of the Mauritanian economy, but the train is just as important to the people, providing a means of transport out of remote communities and access to the outside world.

Three trains run daily between the mines in Zouérat to the Atlantic port of Nouadhibou, and one of these carries passengers. Passengers can ride for free on the iron ore or pay a few dollars for the “luxury” of a hard wooden seat in the carriages. These can be hopelessly overcrowded.

Once the train picks up speed to a maximum of 31 mph (50 km/h), it also gathers the sand from the desert — which explains why I could hardly see the train until it was right in the station.

There is not a single foreigner on the train besides me, and only four other women. I am the object of much interest, although the men visibly relax when I say I am meeting “my husband” in a few days time.

I sit with the lady in the pink dress and share her biscuits and the drool of her one-year-old son. I can only communicate with her by smiles and nods.

Outside is frontier country. It’s hard to believe this lunar-like landscape was once full of lakes, rivers and vegetation. We pass the odd herd of goats, but our only other view is a sandy track that occasionally appears, following the railway line.

La Mauritanie, the land of the Moors, claimed independence from its French colonial rulers in 1960. While you can still find baguettes and croissants at the breakfast table and children who will ask “Donnez-moi un cadeau” (give me a present), the Moorish culture is still by far the more dominant.

Mauritania is almost twice as big as France. Three-quarters of it is desert. With a population of only three million people, it does not even come close to the 11 million living in the greater Parisian metropolitan area alone.

The railway line was built at about the same time as the country’s independence, to take advantage of the sizeable iron-ore deposits in Zouérat. The railway line and the port are close to the territory of Western Sahara, which was disputed between Morocco and Mauritania since nationalism emerged in the 1960s, when nomadic Saharans settled in the region.

The nationalist Polisario Front (mostly Berber inhabitants of the region) waged guerrilla warfare and sabotaged the train until 1979, when the Mauritanian government renounced its claims to the land.

I am grateful that the conflict was resolved. Otherwise there would be more than a fine dust blowing through the window right now. The dust is so constant I soon follow the other passengers’ example and adjust my scarf into a makeshift turban. Within the first hour some passengers produce a gas burner and brew tea.

Biscuits, lollipops, gum and babies are passed around communally. Blankets cover the floor where some of the passengers lounge. The rest of us make do on the rattling benches.

A ghetto blaster provides a steady stream of the latest Mauritanian, African and even Hindi music until, thankfully, it jams, sparing our ears from the constant barrage. Two men spend hours unreeling the cassette tape.

Just before sunset the train slows, seemingly in the middle of nowhere, and an armada of jeeps appears out of the dust to ferry passengers to unknown destinations in the dunes. Unfortunately, my pink-robed friend is one of them. She waves to me when I poke my head out the window.

We rattle off again, and as the last of the sun’s rays stream through the window, everyone in the carriage stands to face Mecca, bow and pray. I feel left out, sitting alone on my seat.

Night falls and torches are brought out. A candle is hung from the ceiling in a cracked plastic bottle. Every drag on a cigarette or pipe lights up the smokers’ features in the gathering gloom. Tea is brewed again, and groups eat by the flickering light.

We have another stop at 9 p.m. Many get off to toilette, or to find a quiet spot in the sand for their ablutions, pray and rest. When we continue, card games, music, conversation, snoring and a crying baby provide accompanying noise to the constant rattle of the carriages.

After 12 hours of travel we slow again as we near Choum at 2 a.m. The carriage comes to life as sleeping bodies are awakened and baggage gathered. Two of the women are heading to Atar, and they shepherd me into a waiting jeep with them. The train pulls off into the night to its final destination Zouérat. Despite its lack of comfort, I feel sad to see it rattle away.

Our journey is not yet over, and it’s another four hours by jeep until we reach Atar along desolate roads, stalling continually. The capital of the Adrar region, in the northwestern part of the country, is considered the real heart of the Sahara, and it seems fitting to arrive wrapped in turbans and scarves with the dirt, dust and iron ore of the desert upon us.

If You Go

Buy tickets at the station before departure. Ask around or look for someone in a SNIM railway shirt carrying a briefcase. Make sure you buy the ticket before you board the train, as you will pay more onboard. Tickets are 1,000 Mauritanian Ouguiya (MRO) (US$ 3.82) for a carriage seat or 3,000 MRO (US$ 11.50) for first class. First-class seats are limited, but they allow access to a smaller room with bunk beds. It does not necessarily ensure more comfort.

It is free to ride on the iron ore, but it can be dangerous, and it’s very cold at night, exposed in the wagons. Blowing desert sand and dust also make it a dirty trip. You may consider it if you have a sleeping bag. Check the departure times, on arrival. The train leaves the Nouadhibou station daily at about 3 p.m. The station is approximately 1.2 miles (2 km) out of town.

When to Go

The winter season, from November through March, is the best time to visit Mauritania, when the weather is quite pleasant.

Other Things to See

Atar is the starting point for many interesting trips in the Adrar region, and the gateway for visiting the ruins of the ancient Moorish cities of Oudane and Chinguetti, both World Heritage sites. If you take the train, get off at Choum and take a shared taxi jeep to Atar (4 hours). You can also get here by plane.

You can visit the ruins of Azougui, 6.2 miles (10 km) to the northwest, with a fort and mausoleum of Imam Hadrami, a holy warrior hero from the 11th century. The pleasant oasis of Terjit is only 12.4 miles (20 km) away.

If you have more time, consider a visit to Chinguetti, the seventh holiest city of Islam. Here, you can tour the old Foreign Legion fort, a 16th century stone mosque and a Koranic library containing ancient manuscripts.

Ouadane is another 87 miles (140 km) northeast from Chinguetti, on the edge of the Adrar plateau. It was founded in 1147 by Berber people, and quickly became a significant caravan and trading center.

Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Mauritania

202-232-5700

- What It’s Like to Live as an Expat: Lake Chapala, Mexico - April 18, 2024

- Top 5 Spots for Stargazing in North Carolina - April 17, 2024

- The Low-Key Magic of Ghent, Belgium - April 17, 2024