Sweaty from a night run, I showered off, only to step back out into the steam room that is Japan mid-August. Hungry and alone, I walked the dark silent streets of my new neighborhood in Zushi, a small beach town about an hour south of Tokyo.

I was tempted to stay in, but my kitchen was as empty as the house we (or rather I) just moved into: my husband Tom deployed on an aircraft carrier less than two weeks after we moved to Japan. Just where he was floating, I had no idea. Nor did I know where to eat.

My first destination failed me. The sushi place I found on Google maps seemed to be closed as I quickly walked by, too nervous to walk in and ask the lady inside if they were open. Truly, I didn’t know how.

Before giving into another onigiri (rice ball) dinner at a conveni (like 7-11 or Family Mart), I remembered passing a shack near the railroad track while walking home from town with a friend the night I moved in.

The shack’s glazed windows were still glowing when I walked up. A white paper sign on the window listed “Last order 10:30” amid rows of handwritten Japanese characters I had yet to learn. So far I’d mastered some simple niceties, like sumimasen (excuse me) and arigatou (thank you). Not yet understanding (let alone aware of) the particular ways in which the Japanese do almost everything – from separating their trash to making tea – I quickly learned the power of a humble, “Gomenasai” (I’m sorry!).

The young woman behind the bar looked up and smiled when I slid the front door open. I nodded in reply to her nod (the compulsory demi-bow being a language even I could understand) then slipped past a chatting couple and into an empty seat around the corner of the bar, which took up most of the small, square front room. The place seemed wall-to-wall pine, not metal, like I’d expected from the corrugated exterior, clothed in some areas with weathered wood.

A one-page menu, all lines and dots and shapes, leaned against the bar. The only English remained outside on the window.

I froze, contemplated walking out, then checked myself. I knew this was bound to happen — that I’d walk into a restaurant, or what I hoped was a restaurant, to find their menu sans English, without even pictures to point to, my crutch for the last few weeks. I just wasn’t ready for it. Not without a friend to giggle with as we politely choked down whatever mysterious dishes arrived at our table after we’d practiced the close-your-eyes- wind-a-finger-and-point technique.

When the young bartender hesitantly approached, I pointed to the Guinness draft. I don’t drink beer, but it was something I could point to. Plus, I was shaky after my run, in desperate need of some calories from whatever kind of food this place served.

I looked around for clues, something else to point at, if I got lucky.

Smoke wafted from the kitchen behind the bar, commingling with the swirls from the couple smoking nearby. The man — appearing younger than his age in trendy, dark-rimmed glasses, toting a dark-haired gaigin (Italian maybe?) he received a nod of approval for from a grey-haired man who later sat at the bar — sang along to a classic rock song I couldn’t recognize. Still, something stirred inside me, the memory of finding my father’s record collection, of listening to “Smoke on the Water” with him for the first time. As a kid, I’d always wished I could go back in time to hang out with my teenage parents, to listen to my uncle’s rock band play live. I never expected to find a taste of it in Japan, let alone inside a shack by a railroad, in a small seaside town.

The bartender handed my pint over the counter along with two bottle caps glued together that I stared at without a clue what they were for until she set the tips of a pair of chopsticks on top. Upcycled chopstick rests. So clever, so Japanese.

I looked up from pretending to read the menu just in time to see the couple’s wooden sticks ting into a narrow cup on the counter.

Finally it clicked. The smoke, the sticks. Yakitori, grilled chicken and vegetables.

“Sumimasen,” I said hesitantly, then pointed to the plate of chicken skewers she’d just passed over the bar to the couple.

The bartender responded in Japanese.

My eyes widened.

Her eyes widened, then she head-bowed and quickly ducked under a half-curtain, back into the kitchen.

Soon appeared a young man, a mix of beach and rock, with long, ebony hair kept at bay by a towel tied around his head. He spoke some English, learned over a few-week holiday in the UK, he said, speaking in slow spurts. Nosuke, pronounced No-skay, is what his friends called him.

Your favorites? I asked, after failing to communicate that I liked vegetables.

He nodded and walked away.

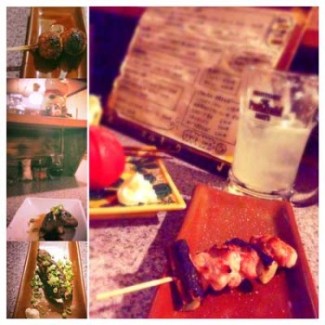

The gnawing in my belly faded after a few sips of beer, and soon the first skewer of chicken arrived. Followed by pinky-sized green peppers, slightly charred. Nosuke sat next to me for a moment after each delivery, both of us working to make sense of each other, nervous laughter being most of what we both could understand.

Skewered meatballs came next followed by the finale, his favorite – small black orbs on a stick. I’m not vegetarian, more of a vegetable preferrer, still seeing the glistening organs made my stomach swirl. I knew they cooked every part of the chicken at yakitori joints, a leave-nothing-to-waste kind of philosophy I can admire, preferably while leaving such delicacies as the heart, skin, and reproductive organs to those who truly enjoy them.

My new friend stood near the edge of the counter, waiting to re-enter the kitchen, watching. I smiled in return, pushing back the urge to also return the plate. Gomenasai!

Instead, my plastic smile stayed put as I dipped the still steaming mystery innards into my special side of spicy miso. My teeth sank into the strangely firm, yet mushy flesh, filling my mouth with a flavor both rich and smoky. The salty spice burned just right. When I grinned his way, his face lit up, as it did when he cleared my empty plates, and again when I promised I’d be back.

Next time, bring your husband, he said with a smile and a final bow I returned before closing the sliding door behind me and walking back out into the night. Though full, I walked home feeling light and a little dizzy in that delightful way the world spins from the perfect buzz, the quenching aftertaste of a fear fizzled out.

Even so, it would take me three months for me to return, to finally bring Tom to the shack. I’d worried, I guess, that I couldn’t recreate that night, that I wouldn’t remember what to order, what to say.

Futatsu negi ma, I said holding up two fingers to the bartender after Tom and I sat down at the bar. Hitotsu shishito to futatsu tsukune to nihonshu… I continued rattling off our order, showing off the words I gleaned from studying other yakitori restaurant’s picture menus to order us leek and chicken, green pepper, and meatballs skewers, along with some sake.

Soon after that familiar towel-bandana peered under the half-curtain from the kitchen.

Bre?

Startled, I took a second to nod. He remembered me too?

We shared a smile before he ducked back into the kitchen, from where he’d dart in and out all night. The smoke-filled shack was packed. Classic rock riffed.

Before we left, Nosuke came around the bar.

Your Japanese is good, he said, nodding approval.

And so is your English! Have you been studying?

He nodded, bashfully. He’d been practicing, he said, for the last three months.

Oishi katta. It was delicious, is all I knew to say.

If You Travel to Japan:

A guide to ordering delicious yakitori

https://food.japan-talk.com/food/new/18-kinds-of-yakitori

And if you visit the beach town of Zushi, be sure to check out “the shack,” which I later learned is called Marukyu: https://www.facebook.com/pages/%E4%B8%B8%E4%B9%85/354413821262206

Author bio: Breawna (Bre) Power Eaton’s first international trip left her stranded with her college roommates as standbys in the Charles de Gaulle airport. Such follies, she learned, only make the travel tales more fun to tell. The freelance writer and English teacher lives in Japan with her husband (until August 2014) and shares her travel tales (i.e. getting lost and unlost around the world, in life, and in love) at breawna.com/lsa-blog/.

- How to Renew a US Passport Quickly and Affordably - April 19, 2024

- 6 Reasons to Visit Portland, Maine (+ Travel Tips) - April 18, 2024

- Cruising with Discovery Princess on the Mexican Riviera - March 30, 2024