Serengeti. It’s another way to say Africa.

Serengeti. It’s another way to say Africa.

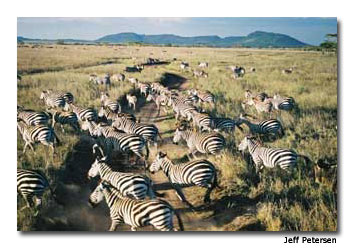

That revelation came to me in an open-topped, four-wheel drive caught in traffic. Animal traffic, that is. More than two million animals thundering north on the great yearly migration – the best time to catch the Serengeti migration is from late May to July – a 3,000 kilometers (1,860 miles) trek from the Ngorongoro Crater in Tanzania, through the Serengeti, to Kenya’s Maasai Mara.

Serengeti. It means “endless plains” in the language of the proud Maasai people. No word is more evocative of an African experience. Just to say it is to roll a Discovery Channel documentary in your head, with endless herds flashing by, and predators picking off stragglers. But to say it is one thing. To see it for yourself is quite something else.

My journey to that Serengeti traffic jam began in Nairobi, the capital of Kenya, and the only city in the world with a game park next door. Like most visitors to East Africa, I had come hoping to see wild animals, and the sight of a giraffe peering over the fence of the airport car park was a clue that I had come to the right place.

From Nairobi, I headed south across the Tanzanian border to Arusha, a five-hour boneshaker on a shuttle bus packed with villagers and tourists. Most roads are dirt and diabolical, and the few asphalt thoroughfares are seemingly maintained not by patching the myriad of massive potholes, but by outlining them in white paint. There are only two speeds – flat out or flat tire – and only one road rule – drivers may overtake only on a blind corner or at the crest of a hill.

The Maasai, who have grazed their animals on the vast plains of the Serengeti for centuries, call the land “Siringitu” (the place where the land moves on forever).

The rattling ride was well worth it, though. For there is no better way to see the passing parade of rural Africa, the umbrella acacia trees and termite nests, mud and thatched huts and village markets. Africa bustles with people going about their business, even if many seem to be in the business of waiting by the road.

There were tribesmen herding cattle and donkeys, people in colorful traditional costume, others in suits and ties. Women were carrying buckets of water on their heads or washing clothes on the rocks in streams. There were men pushing barrows and bicycles loaded with produce, police and soldiers slinging AK-47s, hawkers with ebony carvings, howling: “My friend, my friend, only 10 American dollars! My children are starving!”

Crossing into Tanzania, after a baggage search and visa fee (a single entry tourist visa is US$ 50) at the Namanga border post, we got our first sight of mighty Mount Kilimanjaro, covered in clouds. This giant triple volcano with an elevation of 19,336 feet (5,895 meters) is the highest peak on the entire continent and something like a yardstick for the whole of Africa. On a scale of spectacle, everything in that landscape is off the scale.

Busy, bustling, pleasant Arusha, with a population of 280,000 and a lively market, is the largest town in northern Tanzania. Yet, it feels like no more than a village.

We waved the bus farewell and switched to four-by-four vehicle. Michael Mlomo was our guide. He had 16 years of experience and an impressive knowledge of wildlife and local culture, so we instantly believed him when he promised us the “big five” – lion, elephant, rhino, buffalo and leopard – so-called because they were once the most prized trophies of big game hunters.

And trustworthy Michael delivered on his promise during a whirlwind safari that took us to Ngorongoro Crater and Lake Manyara in Tanzania, and East and West Tsavo in Kenya. Each was a unique setting for wildlife – the grassland of Ngorongoro, home of the black rhino, the jungles of Manyara with its tree climbing lions, and the desert and forest of the Tsavo, where lions were snuffling outside my tent at night. Yet all were added attractions to the greatest spectacle on earth.

A lioness sits in a tree in Tanzania’s Tarangire National Park.us back to that animal traffic jam on the Serengeti. The vast Serengeti Plains span the Kenyan and Tanzanian border and encompass Serengeti National Park (5,800 sqm or 15,000 km²) itself, the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Maswa Game Reserve, the Loliondo, Grumeti and Ikorongo Controlled Areas and the Maasai Mara National Reserve in Kenya. More than 90,000 tourists flock to the Park each year. Two World Heritage Sites and two Biosphere Reserves have been established within this 11,500 square mile (30,000 km²) region.

The unique Serengeti ecosystem is one of the oldest on earth. And the ancient migration of the animals for which this mythical mosaic of grassland and savannas is perhaps most famous is as old as mankind. Each year the migration to fresh grazing grounds starts anew. Over one million wildebeest (also known as gnu), half a million gazelles, 200,000 zebras, 20,000 eland antelopes start moving– from the northern hills to the southern plains for the short rains in October and November. Hungry predators like lions, hyenas and leopards follow this ever-moving feast. Then the animal trek swirls west and north after the long rains in April, May and June. Their instinct is so strong that no drought, gorge or the crocodile infested Mara River can hold them back.

Once, the migration began clockwise, but in recent years the weather phenomenon, El Niño, is believed to have altered the change of seasons, so we bounced into the Park not exactly knowing if the herds were yet on the move or where to find them. The landscape is dead flat except for the odd “kopje,” stone hills inhabited by lions and baboons.

Clouds of dusts caused by millions of trampling hooves and circling vultures high above showed us directions. What looked like a dark forest in the distance turned out to be thousands of beasts on the move. We had finally found what we had come for – animals -as far as the eye could see. Leading the endless procession was the wildebeest, a funny looking beast said to be assembled of leftover parts of other African animals: the horns of its cousin the hartebeest-antelope, the swift long legs of a topi antelope, the shaggy hair of a warthog, the fluffy tail of a giraffe, the miniscule brain of a fly and skeptical face of a grasshopper. Among the wildebeests were zebras. Who had ever expected them to bark like a dog? They were standing in family groups when not on the move, heads resting on the black-and-white striped necks of their kin. In separate processions were elands, gazelles, giraffes, elephants and ostriches.

Here, life and death are on the run, a symbol for the eternal cycle of life. There were lions panting beside fresh kills, limping calves injured in the crush, doomed to be an evening meal, skulking packs of hyena and hunting dogs, crocodiles lurking in waterholes, and in the sky the ubiquitous vultures circling, circling.

Later, as I sat swatting tsetse flies while stalled in animal traffic, I counted myself lucky. Many people come out of Africa complaining they saw fewer wild animals than in a zoo.

For those souls I have but one word of advice: Serengeti.

If You Go

East Africa is a high-risk area for serious infectious diseases. You will need a yellow fever inoculation certificate to re-enter your country, malaria protection and other vaccinations. See a doctor at least six weeks before departure. Cover up and use a good insect repellent. The malaria mosquito and the tsetse fly are fierce and relentless. Don’t drink the water and don’t swim in lakes, which have parasite bugs. Don’t carry valuables or stray onto side streets, especially in Nairobi. Crime is rife. On safari, never leave your vehicle. Wild animals stroll faster than you can run.

Serengeti National Park:

www.serengeti.org

Tanzania Tourist Board:

https://www.tanzaniatouristboard.com/

United Republic of Tanzania:

www.tanzania.go.tz

Kenya Tourist Board:

www.magicalkenya.com