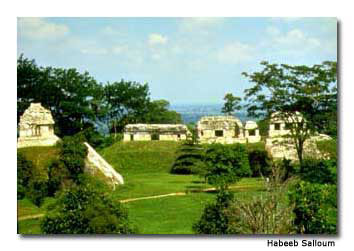

The Palenque ruins are some of the most celebrated and spectacular of all Mayan archaeological sites. The ancient city rises from artificial terraces on a fertile plateau and is surrounded by luxuriant green foliage, rivulets and small waterfalls.

Part of a reserve called Parque Nacional Palenque, the remnants of this once-famous royal residence, are located in the foothills of fern-covered northern mountains in the Mexican state of Chiapas. Monumental temples stand silently in a choking rainforest, sticking out of luscious jungle high above the flood plains of the Usumacinta River. Palenque’s monumental roof-combed structures of white rock, semi-hidden by the emerald rainforest, have earned it the well-deserved title “Jewel of Maya Cities.”

The ruins cover 25 square miles (65 km²), but only 15 percent to 34 percent of the city’s 500 major structures have been excavated. The Spaniards called the town Palenque, which translates into palisade or fortification, when they saw the trees growing out of the ruins like tall stakes.

The Maya called it Otolum meaning “Land with Strong Houses.” Another ancient name for the city wasLakam Ha — “Big Water” or “Wide Water” — for the many springs and cascades that are found within the site. These great Central American builders erected it as a ceremonial center for high priests during the Maya Classic Period (around 300 to 900 A.D.). Reaching its peak between 600 and 700 A.D., it was deserted in the ninth century for reasons as yet unknown.

Palenque’s architects created their own distinctive style, famous for its lightness, using roof combs, sculptured wall panels and corbelled vaults to great effect. Their dramatically located stone temples, some seven stories high, are exceptionally well preserved. These ceremonial structures with their inscriptions, stone sculptures and numerous other unique architectural features are considered to be the most exquisite achievements of the Mayas.

The temples feature a series of decorative motifs found nowhere else. Unlikely as it may seem, some of these appear to be almost Chinese with Phoenician, Canaanite and Moorish influences. In the Palace, one of the most interesting structures, there are even remains resembling a Moorish arch.

Hernán Cortés, the 16th-century Spanish conquistador, passed within 30 miles (48 km) of the site, but did not realize its existence. In later centuries, other Spaniards discovered the ruins. Yet it was only in 1831, due to the writings of eccentric Frenchman Count de Waldeck, who reportedly studied the ruins and lived on top of the temple still carrying his name (Temple of the Count), that the world came to know Palenque.

Among the most important buildings excavated is the Temple of Inscriptions, which is perhaps the most famous of the structures. The Temple of the Sun features the best-preserved roof combs. The Palace impresses with over 176 items of stone carvings. The Temple of the Jaguar sports magnificent bas-reliefs and motifs similar to Oriental art. And Temple XIV contains stucco reliefs associated with the death of King Pakal (603 to 683).

Entering the ruins, the first structure I encountered was the Temple of the Inscriptions, which contains a nine-tiered pyramid 75 feet (23 m) high and a royal mausoleum. It was the only pyramid in Mexico built specifically as a tomb. Well-preserved and restored, the temple was named after a series of stone panels covered with 620 hieroglyphic inscriptions, which were found inside the top story walls.

They contained Palenque’s history and the family tree of King Pakal whose crypt was unearthed in 1952 by archeologist Alberto Ruíz Thuller. The tomb, with Pakal wrapped in jaguar skins, was the first ever discovered inside a Maya pyramid and had lain untouched for a millennium.

Palenque’s rise from a small ceremonial center to a renowned Maya city owes much to the most celebrated of its rulers, Pakal and his successors, Bahlum and Kuk. Called the Mesoamerica Charlemagne, Pakal, after ascending the throne at the age of 15, reigned for some 67 years. His burial vault, covered by a monolithic sepulchral slab, 10 feet (3.5 m) long and 7 feet (2.5 m) wide, was found below the temple floor. A plaster pipe ran along the stairway to the tomb and was meant for air for the four men and a woman who were to accompany him on his journey through the underworld and whose remains were found at the entrance to the crypt. Illogical to the modern mind: Why would air be needed for the dead?

One of the most famous of the Maya kings, Pakal’s burial vault yielded many fine objects. From among the jewels and other exquisite objects found in the tomb were the famous diadem and majestic jade and obsidian masks, now in Mexico City’s Museum of Anthropology.

Most visitors to Palenque descend the 80-foot (24.5 m) flight of stairs inside the Temple of Inscriptions leading down to the mausoleum. The steep stairway is lighted but damp and somewhat slippery. One gets an uncomfortable and eerie feeling, moving downward, thinking that perhaps King Pakal was not in the mood to welcome visitors. However, all is forgotten when a visitor sees the massive sarcophagus, deep in the heart of the pyramid, decorated with a beautiful bas-relief sculpture portraying the death and rebirth of Pakal.

Above ground, you can ascend the broad, but extremely steep, 67-step stairway to the top of the pyramid, where there is an excellent view of the ruins. After examining the inscription panels, I stood surveying the scene. Laid out below was the sweeping panorama of an endless stretch of forest and savannah and, to the back, tree-covered hills, forever lush green due to the annual 200 inches (500 cm) of rain.

I was enchanted with temples intermingled with grassy mounds, tall palm groves and flowing waters — all illuminated by the morning sunlight in an iridescent glow. From this vantage point, the view was breathtaking.

The next stop was the Palace — once the home of Palenque’s Maya kings. The largest architectural work in Palenque, the structure consists of a complex of rooms, patios, squares and false arches, decorated with superb friezes. Overshadowing these architectural gems is a four-story tower, which is believed to have been an observatory. The Palace contains paintings and stone carvings, including one of Pakal and his mother, as well as stucco sculptures — the finest examples of aboriginal art.

Its architecture and sculptures, unique in beauty and technical perfection among the Maya ruins, mark the architectural apogee of the Western Maya Empire to many historians. The remaining colors on the numerous murals; buildings with facilities for running water and what is considered to be man’s first sanitary system; and the impressive rows of stelae (carved stone slabs or pillars), make Palenque undoubtedly the most magical of Maya cities.

If You Go

Mexico Tourism Board

- Mauritius: The Paradise You Didn’t Know You Were Missing - July 18, 2025

- Slow Down and Savor: Why Africa’s Most Elegant Train Journey Should Be Your Next Adventure - July 18, 2025

- How to Plan Your Dream African Safari - July 18, 2025